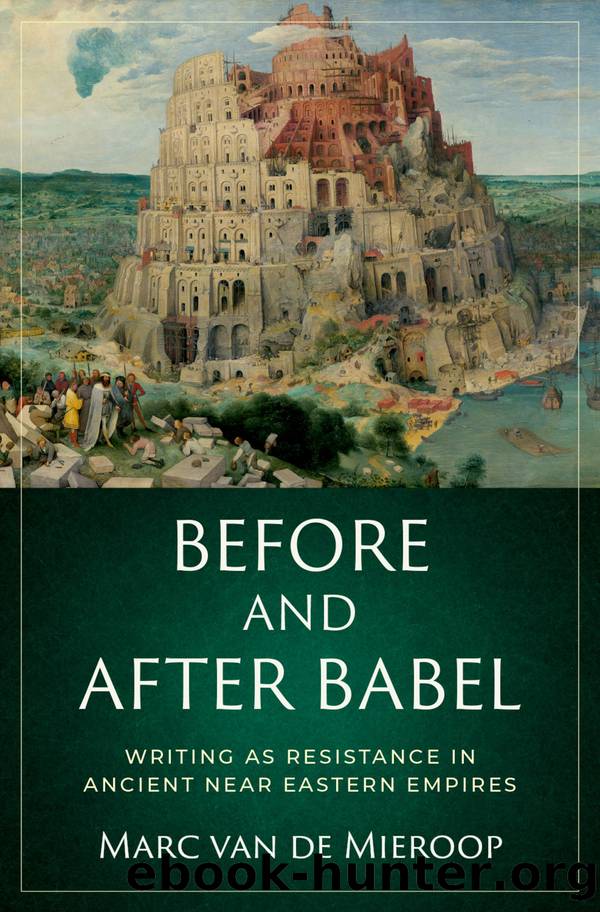

Before and after Babel by Marc Van De Mieroop

Author:Marc Van De Mieroop

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Oxford University Press

Published: 2022-06-15T00:00:00+00:00

Conclusion

Phoenician and Aramaic were two closely related languages and scripts, but different people used them. Although these people lived in proximity to each other, perhaps even in the same places, there are no bilingual texts that combine the two languages, while both of them appeared alongside many other languages on monuments. One either used Phoenician or Aramaicâperhaps the languages were mutually intelligible so no one bothered to render a text in both. Yet they had different histories. Phoenician was already recorded in the second millennium, and the alphabetic script that would influence all others was invented late in that millennium to write it. In the first millennium its users were residents of flourishing mercantile cities with far-flung contacts. They inspired Neo-Hittite rulers who regularly carved inscriptions in Phoenician alongside their own language and script, hieroglyphic Luwian. Aramaic, however, was a newcomer in the written record whose popularity grew rapidly, probably because so many people spoke the language. It became the script Syrian elites used on their monuments and gradually replaced Phoenician in such places as Samâal. It was used in opposition to Assyrian cuneiform to stress non-Assyrian identity, even by people whose position depended on the empire. Ironically the empires guaranteed Aramaicâs success, because they started to use it for administrative purposes. That practice climaxed under the Achaemenid Persians, who employed the language and its script for their transregional system of accounting and imperial correspondence, and the available corpus of such writings became very substantial. In contrast, no Phoenician administrative documents have survived. Considering the Phoenicians were such great traders who must have accounted for their transactions, it is most likely these were all lost. Also the literature and scholarship in the Phoenician language have disappearedâif they ever existedâwhereas there are some scant remains of literature in Aramaic. The creation of that literature, too, needs to be considered within the context of empires, as an act of resistance. And it was the beginning of a long literary tradition that gave Aramaic a much greater long-term impact than Phoenician. Both cases, however, show how vernaculars in the first millennium became commonly recorded with wide-ranging effects. We will turn now to another language of the Levant, Hebrew, to explore the literate culture of the ancient Near East that had the greatest impact in later world history.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Bahrain | Egypt |

| Iran | Iraq |

| Israel & Palestine | Jordan |

| Kuwait | Lebanon |

| Oman | Qatar |

| Saudi Arabia | Syria |

| Turkey | United Arab Emirates |

| Yemen |

Empire of the Sikhs by Patwant Singh(23064)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(5084)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4766)

The Templars by Dan Jones(4676)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(4193)

12 Strong by Doug Stanton(3541)

Blood and Sand by Alex Von Tunzelmann(3184)

Babylon's Ark by Lawrence Anthony(2666)

The History of Jihad: From Muhammad to ISIS by Spencer Robert(2614)

No Room for Small Dreams by Shimon Peres(2355)

The Turkish Psychedelic Explosion by Daniel Spicer(2349)

Inside the Middle East by Avi Melamed(2347)

Gideon's Spies: The Secret History of the Mossad by Gordon Thomas(2329)

Arabs by Eugene Rogan(2291)

The First Muslim The Story of Muhammad by Lesley Hazleton(2257)

Come, Tell Me How You Live by Mallowan Agatha Christie(2244)

Bus on Jaffa Road by Mike Kelly(2144)

1453 by Roger Crowley(2018)

Kabul 1841-42: Battle Story by Edmund Yorke(2014)