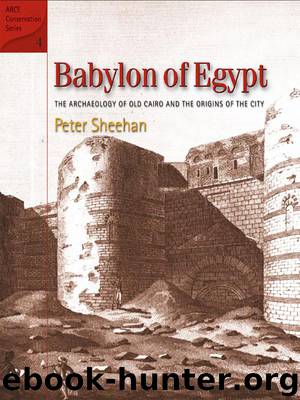

Babylon of Egypt: The Archaeology of Old Cairo and the Origins of the City

Author:Peter Sheehan [Sheehan, Peter]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Published: 2016-03-02T16:00:00+00:00

[W]ith the British occupation came a sense of security which has led to the most deplorable destruction. The need of a fortified enclosure having vanished, Copts, Greeks, and Jews vied together in demolishing the walls.… It is the simple truth that in the last eighteen years more havoc has been wrought upon the Roman fortress than in the previous eighteen centuries.⁴⁴

For the northern wall, however, it seems more plausible that the demolition occurred at the very beginning of the early medieval period, and actually formed an integral part of the transition from fortress to city. The striking contrast between the southern flanking tower of the East Gate, preserved to its full height, and the northern tower, razed to the ground, suggests that the absence of the northern walls above ground may have resulted from a deliberate act of planning. Given the scale of the preserved walls it is clear that the demolition of even one side would also have produced a vast amount of building material for use in the new town.

The fate of the fortress north of the via principalis may reflect either a different character of the Roman buildings in this area or the nature of their reuse in the early medieval period. We have briefly considered the possibility that part of the Diocletianic fortress may have functioned as a kind of imperial residence or palace analogous with the emperor’s famous retreat at Split in modern Croatia.⁴⁵ We also know that the central quarter of al-Fustat around the Mosque of ‘Amr, the district known as Khittat Ahl al-Raya, was the preferred district for aristocratic residences from the very beginnings of al-Fustat.⁴⁶ Thus the conquerors may simply have removed the north wall and annexed the former imperial quarter of the fortress for the use of their elite within the ‘new’ settlement north of the via principalis. Although the existence of imperial or public buildings in the northern part of the fortress has not been proven by excavation it seems likely that at the very least the fortress north of this point was appropriated for new buildings at the foundation of al-Fustat. The via principalis would have made a logical dividing line for the extension of settlement, for, as we have seen, its relationship to the bridge across the Nile made it perhaps the most important route of the fortress. This link to the west bank of the Nile was made even more important by the location at the western end of the bridge of an important and often overlooked part of al-Fustat, the fortified ‘suburb’ of Giza.⁴⁷ The fortifications of this area were essential to the protection of the bridge and, like the bridge itself, were no doubt Roman in origin. The numerous churches, monasteries, and a large ancient synagogue mentioned in the historical sources make it clear that Giza, like Babylon, was part of the same ancient settlement situated on either side of the river crossing.

Whatever their origins, the disappearance of the early medieval buildings in the north

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Bahrain | Egypt |

| Iran | Iraq |

| Israel & Palestine | Jordan |

| Kuwait | Lebanon |

| Oman | Qatar |

| Saudi Arabia | Syria |

| Turkey | United Arab Emirates |

| Yemen |

Empire of the Sikhs by Patwant Singh(22167)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(4421)

The Templars by Dan Jones(4182)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4009)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(3508)

12 Strong by Doug Stanton(3052)

Blood and Sand by Alex Von Tunzelmann(2606)

The History of Jihad: From Muhammad to ISIS by Spencer Robert(2203)

Babylon's Ark by Lawrence Anthony(2066)

No Room for Small Dreams by Shimon Peres(1987)

The Turkish Psychedelic Explosion by Daniel Spicer(1986)

Gideon's Spies: The Secret History of the Mossad by Gordon Thomas(1947)

Inside the Middle East by Avi Melamed(1937)

The First Muslim The Story of Muhammad by Lesley Hazleton(1880)

Arabs by Eugene Rogan(1833)

Bus on Jaffa Road by Mike Kelly(1781)

Come, Tell Me How You Live by Mallowan Agatha Christie(1764)

Kabul 1841-42: Battle Story by Edmund Yorke(1648)

Citizen Strangers by Robinson Shira N.;(1534)