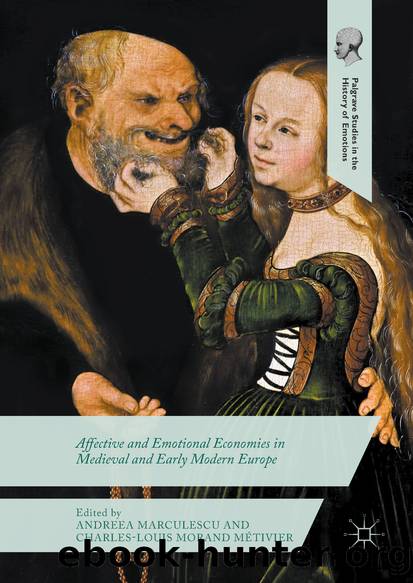

Affective and Emotional Economies in Medieval and Early Modern Europe by Andreea Marculescu & Charles-Louis Morand Métivier

Author:Andreea Marculescu & Charles-Louis Morand Métivier

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Springer International Publishing, Cham

Blazons and Lovesick Subjects

Here’s Berlant, again on convention:What does it mean about love that its expressions tend to be so conventional, so bound up in institutions like marriage and family, property relations, and stock phrases and plots?…[this conventionality ] suggests…that love can be at once genuine and counterfeit, shared and hoarded, apprehensible and enigmatic. ( Desire / Love 7)

The question of whether lyric desire is physically felt by a lyric speaker (in Berlant’s terms, “genuine”) or is rather purely conventional (“counterfeit”) is, of course, impossible to answer. However, it is certainly possible to trace how, in the lyrics, desire is expressed as embodied by a textual “I.” Two instances in which embodied desire can be seen most clearly as conventional are the blazon (which focuses on the body of the love object, who is nearly always female) and in descriptions of the effects of lovesickness (in which the focus is firmly on the body of the medieval speaking subject or lover, usually male). In both tropes, desire is frequently experienced by the poem’s reader or hearer in a way that is abstract, non-physiological, due to extremely conventional language that does not allow any access to an individualized subject or love object. As is readily apparent to anyone with even minimal experience with Middle English lyrics, all lovesick subjects behave in more or less the same manner: they are unable to sleep, eat, or stop thinking about the love object; they “groan” and “sorrow” and pine; they feel and act as if insane. The objects of desire in these poems are often no more individuated; in fact, most are conventional to the point of absolutely effacing any individualized traits of a particular woman. Characteristics of the love object usually include grey eyes; high, arched eyebrows; a sweet, kissable mouth; a rosy complexion; long hair; a slender waist; long, thin fingers; plump arms; and skin that is white as a lily or as whalebone. In Desire / Love , Berlant notes that in psychoanalytic thought “the will to destroy (the death drive) and preserve (the pleasure principle) the desired object are two sides of the same process” (25). Indeed, the most conventional of these poems, while purportedly immortalizing the love object, in fact efface or destroy her entirely, eliding any distinguishing marks of embodied individuality even in their quest to praise and preserve her as the exemplar of idealized beauty.

However, in some lyrics, experiencers are able to empathize with and respond to the textual subject and/or the love object as an individual even through conventional language. To close, I will examine several poems that include divergent variations on the same image. Although variants of this image appear frequently in surviving Middle English lyrics, slight differences in phrasing in each poem provide subtle but significant changes in the ways readers or hearers receive the lyric on an embodied level. This image is variously expressed, but in all cases refers (usually somewhat obliquely) to the beauty of a woman under her clothing. In every

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Room 212 by Kate Stewart(4105)

The Crown by Robert Lacey(4105)

Endurance: Shackleton's Incredible Voyage by Alfred Lansing(3840)

The Iron Duke by The Iron Duke(3639)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(3515)

Killing England by Bill O'Reilly(3454)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(3257)

Say Nothing by Patrick Radden Keefe(3060)

I'll Give You the Sun by Jandy Nelson(2842)

Hitler's Monsters by Eric Kurlander(2731)

Shadow of Night by Deborah Harkness(2718)

Margaret Thatcher: The Autobiography by Thatcher Margaret(2683)

Mary, Queen of Scots, and the Murder of Lord Darnley by Alison Weir(2677)

Darkest Hour by Anthony McCarten(2644)

Blood and Sand by Alex Von Tunzelmann(2608)

Red Famine: Stalin's War on Ukraine by Anne Applebaum(2461)

Eleanor & Park by Rainbow Rowell(2393)

The One Memory of Flora Banks by Emily Barr(2348)

Book of Life by Deborah Harkness(2263)