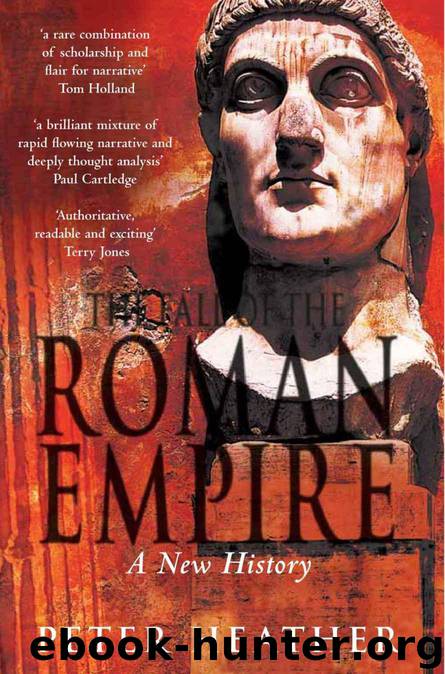

The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History by Peter Heather

Author:Peter Heather

Language: eng

Format: mobi, epub

Tags: Classical History

Publisher: Pan Books

Published: 2010-09-30T15:00:00+00:00

7

ATTILA THE HUN

FOR OVER A DECADE, from 441 to 453, the history of Europe was dominated by military campaigns on an unprecedented scale – the work of Attila, ‘scourge of God’. Historians’ opinions about him have ranged from one end of the spectrum to the other. After Gibbon, he tended to be viewed as a military and diplomatic genius. Edward Thompson, writing in the 1940s, sought to set the record straight by portraying him as a bungler. To Christian contemporaries, Attila’s armies seemed like a whip wielded by the Almighty. His pagan forces ranged across Europe, sweeping those of God-chosen Roman emperors before them. Roman imperial ideology was good at explaining victory, but not so good at explaining defeat, especially at the hands of non- Christians. Why was God allowing the unbelievers to destroy His people? In the 440s, Attila the Hun, spreading devastation from Constantinople to the gates of Paris, prompted this question as it had never been prompted before. As one contemporary put it, ‘Attila ground almost the whole of Europe into dust.’1

The Loss of Africa

ATTILA BURSTS into history as joint ruler of the Huns with his brother Bleda. The pair inherited power from an uncle, Rua (or Ruga; still alive in November 435).2 The first recorded east Roman embassy to Attila and Bleda was sent sometime after 15 February 438, and it is likely that the brothers came to power only at the end of the 430s, possibly as late as 440. Their debut brought changes of policy, as new regimes usually do. Initial contacts with Constantinople led to a decision to renegotiate the existing relationship between the two parties. Their representatives met outside the city of Margus on the Danube in Upper Moesia (map 11). The fifth-century historian Priscus treats us to this detail:3 ‘the [Huns] do not think it proper to confer dismounted, so that the Romans, mindful of their own dignity, chose to meet [them] in the same fashion, lest one side speak from horseback, the other on foot.’

The salient feature of the new agreement was an increase in the amount of the annual subsidy paid to the Huns, from 350 pounds of gold to 700. The treaty also agreed the terms under which Roman prisoners might be returned and where and how markets would be conducted; also, that the Romans would receive no refugees from the Hunnic Empire. But the new terms, despite the increased payments, did not satisfy the Huns’ new leaders. Shortly afterwards at a market, probably in winter 440/1, Hunnic ‘traders’ suddenly produced their weapons and seized the Roman fort in which the market was being held, killing the guards as well as some of the Roman merchants. According to Priscus, when a Roman embassy complained, the Huns retorted that ‘the bishop of Margus had crossed over to their land, and searching out their royal tombs, had stolen the valuables stored there.’ But our episcopal Indiana Jones was only a pretext. Taking the opportunity to raise the issue of refugees

Download

The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History by Peter Heather.epub

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Room 212 by Kate Stewart(5105)

The Crown by Robert Lacey(4806)

Endurance: Shackleton's Incredible Voyage by Alfred Lansing(4769)

The Iron Duke by The Iron Duke(4349)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(4203)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(4100)

Killing England by Bill O'Reilly(3995)

Say Nothing by Patrick Radden Keefe(3975)

I'll Give You the Sun by Jandy Nelson(3428)

Shadow of Night by Deborah Harkness(3359)

Hitler's Monsters by Eric Kurlander(3328)

Mary, Queen of Scots, and the Murder of Lord Darnley by Alison Weir(3200)

Blood and Sand by Alex Von Tunzelmann(3195)

Eleanor & Park by Rainbow Rowell(3151)

Darkest Hour by Anthony McCarten(3119)

Margaret Thatcher: The Autobiography by Thatcher Margaret(3079)

Book of Life by Deborah Harkness(2931)

Red Famine: Stalin's War on Ukraine by Anne Applebaum(2928)

The One Memory of Flora Banks by Emily Barr(2857)