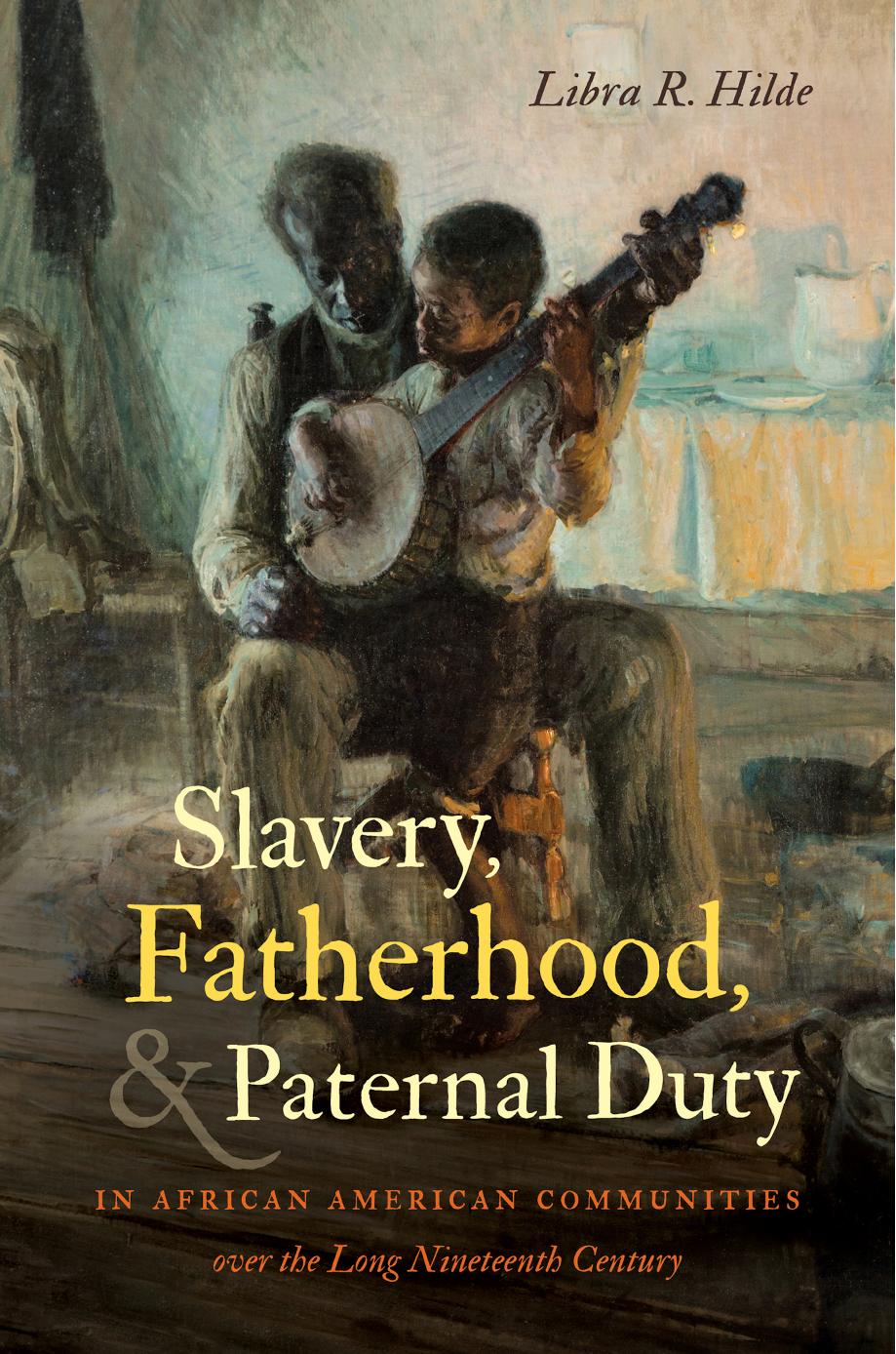

Slavery, Fatherhood, and Paternal Duty in African American Communities over the Long Nineteenth Century by Libra R. Hilde

Author:Libra R. Hilde [Hilde, Libra R.]

Language: eng

Format: epub, pdf

ISBN: 9781469660677

Barnesnoble:

Publisher: The University of North Carolina Press

Published: 2020-10-19T00:00:00+00:00

CHAPTER SEVEN

My Children Is My Own

Fatherhood and Freedom

In a commentary addressed to his former owner and published in 1855, Frederick Douglass outlined the meaning of freedom for a father, calling his four children âperfectly secure under my own roof. There are no slaveholders here to rend my heart by snatching them from my arms, or blast a motherâs dearest hopes by tearing them from her bosom. These dear children are oursânot to work up into rice, sugar, and tobacco, but to watch over, regard, and protect, and to rear them up in the nurture and admonition of the gospelâto train them up in the paths of wisdom and virtue, and, as far as we can, to make them useful to the world and to themselves.â Douglass felt it was his duty to provide moral and religious guidance and set his children on a path of future promise. âA slaveholder never appears to me so completely an agent of hell, as when I think of and look upon my dear children,â he concluded. Freedom enabled men to protect and provide for their family, and antebellum fugitives contrasted their conception of honorable fatherhood with the base immorality of home-wrecking slaveholders.1

Douglass wrote from the perspective of a man who had been free for almost two decades and attained a measure of success. Writing a decade later, having only recently achieved freedom in the aftermath of the Civil War, Jourdan Anderson laid out a nearly identical vision of masculine duty and condemnation of slaveholder paternalism. In a sarcastic reply to a letter from his former master, who wanted Anderson to return to the plantation, Anderson revealed his understanding of paternal duty and the meaning of freedom. Besides asking his former master to forward back wages as a sign of good faith, Anderson discussed his apprehensions about returning to the South, noting that all of his children attended school and his son showed signs of becoming a preacher. âIn answering this letter please state if there would be any safety for my Milly and Jane, who are now grown up and both good-looking girls. You know how it was with poor Matilda and Catherine. I would rather stay here and starve, and die if it comes to that, than have my girls brought to shame by the violence and wickedness of their young masters,â Anderson wrote in an open acknowledgment of the sexual degradation of slavery. âYou will also please state if there has been any schools opened for the colored children in your neighborhood, the great desire of my life now is to give my children an education, and have them form virtuous habits.â Like prewar fugitives, Anderson saw it as his responsibility to protect his children, provide moral guidance, ensure they received a proper education, and prepare them for a respectable future. He defined slavery as the sins of the white patriarchy enacted on a long-suppressed and emerging black patriarchy. âWe trust the good Maker has opened your eyes to the wrongs which

Download

Slavery, Fatherhood, and Paternal Duty in African American Communities over the Long Nineteenth Century by Libra R. Hilde.pdf

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| General | Men |

| Women in History |

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32548)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31947)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31932)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(31917)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19034)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(15958)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14488)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(14057)

For the Love of Europe by Rick Steves(13915)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(13349)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(13349)

Fifty Shades Freed by E L James(13233)

Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit by John E. Douglas & Mark Olshaker(9324)

Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan(9279)

The Lost Art of Listening by Michael P. Nichols(7494)

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress by Steven Pinker(7306)

The Four Agreements by Don Miguel Ruiz(6745)

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou(6611)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6265)