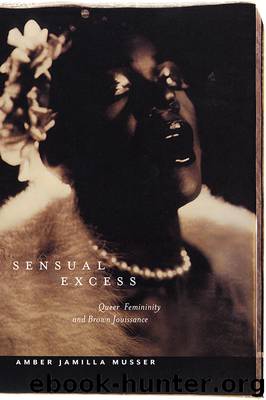

Sensual Excess by Amber Jamilla Musser

Author:Amber Jamilla Musser

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: LIT004020 Literary Criticism / American / General

Publisher: New York University Press

5

Weeping Machines

Automaticity, Looping, and the Possibilities of Perversion

Neapolitan (2003) invites spectators to sit on a bench covered in a crocheted cozy to watch a television that plays a fourteen-minute loop of Nao Bustamante watching a projected loop of the end of the Cuban film Fresa y Chocolate (1993). Bustamante cries during the final scene, pausing only to wipe her eyes with a hanky before she rewinds to re-watch the end and cry again. Patty Chang’s In Love (2001) pairs a monitor that shows Chang and her mother locked in a passionate kiss with another monitor showing a video of her doing the same to her father while tears stream down everyone’s faces. As the film progresses, the action unspools backward; we see that what appeared to be a kiss was both of them sharing an onion. With Neapolitan and In Love, Bustamante and Chang perform women on the verge. While Bustamante and Chang cry and cry and cry, catharsis is just out of reach. Just as spectators begin to imagine resolution, the videos begin again.

Bustamante’s and Chang’s inhabitations of hysteria and perversion reveal the divergent ways that racialization positions these performances of responsiveness as excessive. This version of brown jouissance is akin to what José Esteban Muñoz calls “brown feeling,” which “chronicles a certain ethics of the self that is utilized and deployed by people of color and other minoritarian subjects who don’t feel quite right within the protocols of normative affect and comportment.”1 These brown feelings are Muñoz’s mode of describing “the ways in which minoritarian affect is always, no matter what its register, partially illegible in relation to the normative affect performed by normative citizen subjects.”2 I come to this articulation of brown jouissance by combining Muñoz’s investment in thinking with feeling as a mode of non-normativity with Dana Luciano’s argument that affective comportment be linked to sexuality. While Luciano centers her discussion on grief, she invites us to think more broadly about emotionality in relation to sexuality. Luciano writes that grief “constitutes a crucial dimension of the dispositif of sexuality itself: the modern intensification of the body, its energies, and its meanings.”3 Hence, I argue that we can understand Bustamante’s and Chang’s performances of emotion as part of a constellation of sexuality because they are legible through norms of labor, intimacy, and brown femininity.

Bustamante’s crying can be indexed to stereotypes of the overly sensitive, hysterical Latina, while Chang’s crying can be attached to the specter of the insensate assimilated Asian American. Through their occupation of opposite sides of the spectrum of “appropriate” emotionality, Bustamante’s and Chang’s performances of crying illuminate the complexity of brown feminine performances of emotion. These performances oscillate between grief, happiness, relief, and pain and resist any fixed reading. That is what makes them arresting works of art to think with, but in their divergence each also highlights the contours of what constitutes normative comportment and the underlying assumption that black and brown people do not feel, they merely react. This is a legacy

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| African-American Studies | Asian American Studies |

| Disabled | Ethnic Studies |

| Hispanic American Studies | LGBT |

| Minority Studies | Native American Studies |

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32538)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31935)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31925)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(31911)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19032)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(15927)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14476)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(14046)

For the Love of Europe by Rick Steves(13872)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(13341)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(13332)

Fifty Shades Freed by E L James(13228)

Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit by John E. Douglas & Mark Olshaker(9313)

Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan(9271)

The Lost Art of Listening by Michael P. Nichols(7487)

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress by Steven Pinker(7303)

The Four Agreements by Don Miguel Ruiz(6739)

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou(6610)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6261)