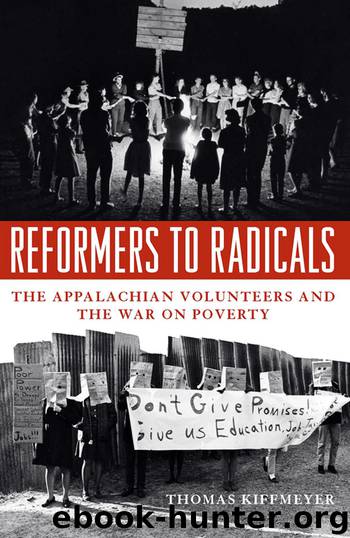

Reformers to Radicals by Thomas Kiffmeyer

Author:Thomas Kiffmeyer

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9780813173085

Publisher: The University Press of Kentucky

6

Operation Rolling Thunder

The Political Education of Mountaineers and Appalachian Volunteers

The message should be one of reform, self help, determination, and a vigorous fighting stand such as that assumed by the Southern Negro in his struggle for civil liberties.

I hope the Appalachian Volunteers will carry out this possibility and that they will become a great new force struggling for reform for the region’s institutions and attitudes.

—Whitesburg attorney and CSM Board of Directors

member Harry Caudill to Milton Ogle, May 4, 1966

The Louisville native and University of Kentucky student Joe Mulloy, much like his counterpart, George Brosi, was unusually attentive for a Southern college student in the early 1960s. Though he did not readily recall President Johnson’s declaration of a “war on poverty,” he was impressed by the civil rights movement, the Freedom Rides of 1963, and Freedom Summer in 1964. “That’s the kinda stuff,” he later recounted, “I was listening to or paying attention to.” Then, at one point in 1964, Mulloy heard the Appalachian Volunteers (AVs) field representative Jack Rivel speak on campus. Rivel “made a good case for getting involved with things in our society and trying to be a part of the solution instead of being part of the problem.” Because its “focus . . . was working with school children,” the “student oriented program” about which Rivel spoke “impressed” Mulloy. As he remembered: “It was something I could do on a weekend and I could connect, somehow, with what was going on in the world.” Further, because, by the end of that calendar year, the federal government, through agencies such as the Area Development Administration and the Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO), looked to the nascent AV program as a model for reform efforts across the country, Mulloy “felt as if we were part of something bigger than just going out there on weekends.”1

Mulloy constructed a number of recreational areas and basketball goals, installed new windows and drywall, and painted a number of schoolhouses on these weekend projects. The Appalachian Volunteers, he stated, “assist[ed] local school boards, . . . supplying some things that everybody else in the state had, but because of the unemployment . . . counties in eastern Kentucky didn’t have.” In addition, these relatively quick weekend efforts allowed the student volunteers to see the “concrete . . . physical result” of their work, and, thus, as other AVs recalled, it “provide[d] a meaningful experience” for the college students.2

After gaining some experience, Mulloy recalled, “we, the younger group of AVs,” began to disagree with the tack taken by the Council of the Southern Mountains (CSM). While the Council followed the course prescribed by those “conservative church-related” folks that Loyal Jones described, the AVs, who worked at the “furthest out places, . . . the most remote ‘head-of-the-holler,’” assumed a different approach. Though it was not “consciously decided upon or thought out,” this new direction “didn’t blame the victim” the way, the AVs believed, the CSM did. Describing the new strategy as an “evolving thing,” Mulloy claimed that it grew from a “give and take process between us and the people we were working with.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anthropology | Archaeology |

| Philosophy | Politics & Government |

| Social Sciences | Sociology |

| Women's Studies |

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32558)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(32020)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31956)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31942)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19047)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(16031)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14508)

For the Love of Europe by Rick Steves(14124)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(14077)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(13371)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(13370)

Fifty Shades Freed by E L James(13243)

Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit by John E. Douglas & Mark Olshaker(9344)

Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan(9293)

The Lost Art of Listening by Michael P. Nichols(7506)

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress by Steven Pinker(7314)

The Four Agreements by Don Miguel Ruiz(6765)

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou(6622)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6281)