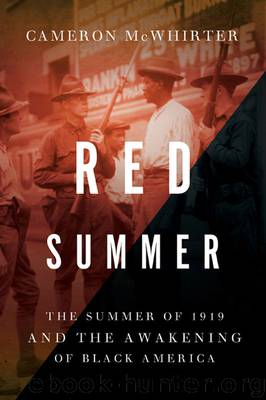

Red Summer by Cameron McWhirter

Author:Cameron McWhirter

Language: eng

Format: azw3, epub

Publisher: Henry Holt and Co.

Published: 2011-07-19T05:00:00+00:00

17.

A New Negro

Brothers we are on the Great Deep. We have cast off on the vast voyage which will lead to Freedom or Death.

—W. E. B. DU BOIS, The Crisis, September 1919

By early September, racial hostility was pandemic. In San Francisco, soldiers and sailors from the Presidio attacked a black neighborhood after blacks beat a drunken sailor for insulting them. More than a thousand servicemen, armed with weapons stolen from shooting galleries, vowed to clean out the Barbary Coast. Police and Navy provost guards had to quell the fighting.1

In Harlem, a black mob scuffled with a plainclothes police officer after he shot and killed a black man. Other whites gathered to defend the officer and more shots were fired. Some in the crowd shouted, “Lynch him!” as other police came to whisk away the injured officer. Police went through the neighborhood wielding billy clubs on those who would not disperse.2

Lynchings continued in the South, including in places like Monroe, Louisiana; Jacksonville, Florida; and Oglethorpe County, Georgia. In Memphis, a white mob tried to lynch Henry Johnson, a black driver who struck and slightly injured some white children with his car. The mob placed a noose around Johnson’s neck when a white man, Jack Stewart, intervened, telling the mob to let police handle the matter. Instead, the crowd tried to hang him as well. Police rescued the two just in time.3 Other minorities became victims. In Pueblo, Colorado, a mob seized two Mexican immigrants accused of killing a police officer and hanged them from a bridge. Police and volunteers were put on duty during the night and the next day to stop any further trouble as hundreds of Mexican immigrants filed through the morgue to view the bodies. No one was arrested for the lynchings.4

Police across the country conducted riot drills and stockpiled riot equipment. In September, Savannah police said they did not expect trouble in their city, yet they purchased pump-action shotguns, bayonets, riot guns, and 10,000 rounds of ammunition.5 State militias were put on alert.

Pundits and politicians offered up analysis of and solutions for the escalating “Negro problem.” William Monroe Trotter’s National Equal Rights League pushed for the United States to take over some or all of Imperial Germany’s African colonies and encourage black Americans to colonize them.6 A black mailman from New Orleans wrote Woodrow Wilson outlining a plan for a government loan program to keep black farmers in the South. The plan required blacks to pay into a fund that then would invest in property and aid black agriculture. “There must be a complete revolution in sentiment as to the status of the Negro,” W. W. Kerr wrote. Wilson did not respond.7

On the bucolic campus of Alabama’s Tuskegee Institute, that bastion of racial acquiescence, Booker T. Washington’s political heir Robert Moton watched the unfolding crisis with astonishment. Washington had promised a segregated but prosperous South, where the social role of African Americans would be secondary but secure. This concept of a benevolent, segregated society, embodied in Washington’s

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| African-American Studies | Asian American Studies |

| Disabled | Ethnic Studies |

| Hispanic American Studies | LGBT |

| Minority Studies | Native American Studies |

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32558)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(32019)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31956)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31942)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19046)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(16029)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14508)

For the Love of Europe by Rick Steves(14121)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(14076)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(13370)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(13366)

Fifty Shades Freed by E L James(13241)

Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit by John E. Douglas & Mark Olshaker(9343)

Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan(9292)

The Lost Art of Listening by Michael P. Nichols(7506)

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress by Steven Pinker(7314)

The Four Agreements by Don Miguel Ruiz(6765)

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou(6622)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6281)