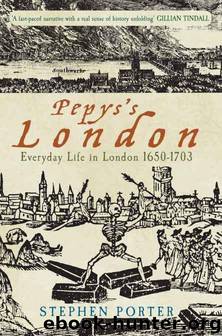

Pepys's London: Everyday Life in London 1650-1703 by Porter Stephen

Author:Porter, Stephen [Porter, Stephen]

Language: eng

Format: mobi, epub

Publisher: Amberley Publishing

Published: 2012-05-14T23:00:00+00:00

7

A Wasp’s Nest

Lingering resentment over the events of the Civil War and regicide was only one of the tensions that troubled relations between the citizens and the court. The Restoration religious settlement and the enforcement of penal measures against nonconformists fuelled the citizens’ ill feeling, and many were offended by the all-too-obvious licentiousness of the court. They were also increasingly concerned by the apparent influence of Roman Catholics and, as the years passed and the king did not produce an heir, the likelihood that his brother James, an avowed Catholic from 1673, would become king. Those tensions flared up into a crisis in the late 1670s, with the court’s supporters and critics acting out their rivalries on London’s streets. This rumbled on into the next decade and, as part of the political manoeuvrings, the City’s charter was withdrawn. The capital witnessed another upheaval in 1688, when James, who had become king, fled and London was once again occupied by an army.

The antipathy evident in the courtiers’ reaction to the news of the Great Fire was indicative of their attitude. For their part, many citizens viewed with distaste the immorality of Charles and James, and the courtiers’ extravagance, debauchery, indolence and frivolity. Pepys was aware of the behaviour at court as early as the summer of 1661, and was afraid of the impact it might have on the conduct of government business: ‘at Court things are in very ill condition, there being so much aemulation, poverty, and the vices of swearing, drinking, and whoring, that I know not what will be the end of it but confusion’. A few days later, when he was told of ‘the vices of the court’, he noted that, ‘the pox is as common there … as eating and swearing’. Things had not changed by the end of the reign, according to Evelyn, who, although loyal to the Stuart monarchy, found it difficult to stomach what he witnessed. Shortly before Charles’s death he wrote that: ‘I saw this evening such a sceane of profuse gaming, and luxurious dallying & prophanesse, the King in the middst of his 3 concubines, as I had never before.’1 Pepys and Evelyn had to go to Whitehall because of their official duties, but the lives of most citizens did not impinge upon those of the courtiers. Yet they could not fail to know about the goings-on at court, through gossip and pamphlets which criticised and lampooned both it and the conduct of government. And they were occasionally made more directly aware of the courtiers’ scandalous behaviour by incidents such as the murder of a watchman, carrying out his duties, by a group of aristocratic young rakehells that included the Duke of Monmouth, Charles II’s illegitimate son.

Londoners did express their resentment occasionally, such as during the Bawdy House riots in March 1668. These disturbances continued the tradition of smashing up brothels over the Easter period. But that year they were given an extra edge when the apprentices proclaimed, ‘that if the King did not give them liberty of conscience, that May-day must be a bloody day’.

Download

Pepys's London: Everyday Life in London 1650-1703 by Porter Stephen.epub

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| General | Channel Islands |

| England | Northern Ireland |

| Scotland | Wales |

Room 212 by Kate Stewart(5040)

The Crown by Robert Lacey(4728)

Endurance: Shackleton's Incredible Voyage by Alfred Lansing(4683)

The Iron Duke by The Iron Duke(4293)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(4139)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(4016)

Killing England by Bill O'Reilly(3953)

Say Nothing by Patrick Radden Keefe(3903)

I'll Give You the Sun by Jandy Nelson(3359)

Shadow of Night by Deborah Harkness(3306)

Hitler's Monsters by Eric Kurlander(3269)

Mary, Queen of Scots, and the Murder of Lord Darnley by Alison Weir(3152)

Blood and Sand by Alex Von Tunzelmann(3140)

Darkest Hour by Anthony McCarten(3072)

Eleanor & Park by Rainbow Rowell(3063)

Margaret Thatcher: The Autobiography by Thatcher Margaret(3029)

Red Famine: Stalin's War on Ukraine by Anne Applebaum(2874)

Book of Life by Deborah Harkness(2869)

The One Memory of Flora Banks by Emily Barr(2803)