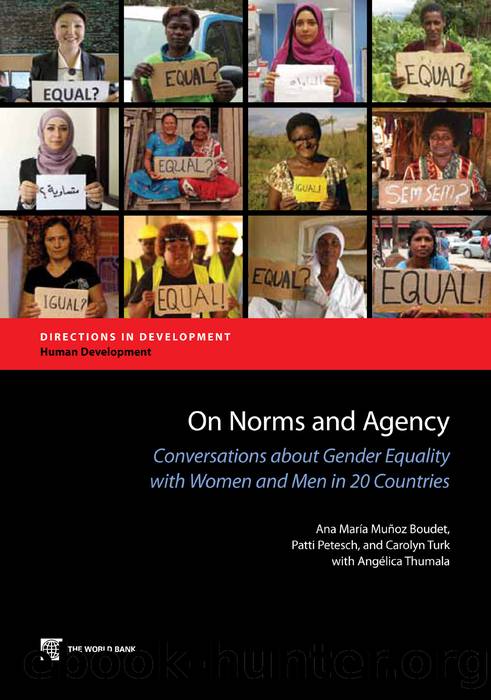

On Norms and Agency: Conversations about Gender Equality with Women and Men in 20 Countries by Ana María Muñoz Boudet; Patti Petesch; Carolyn Turk; Angélica Thumala

Author:Ana María Muñoz Boudet; Patti Petesch; Carolyn Turk; Angélica Thumala

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: The World Bank

âFirst Comes Love, Then Comes Marriage, Then Comes Baby in a Baby Carriageâ

From early in life, we face constant reminders of the relations expected between women and men. Even playground games and songsâsuch as the title of this section,12 which is a song used by children to taunt boys and girls seen as getting too close or too romantic with each otherâcharge our lives with gender signification. Thorne (1993) refers to this process as gender play and children, as well as adults, recreate gender in everything they do, such as creating a couple when they see a boy and girl together. For most children, when they grow up, this becomes a reality. Starting a new household and having children are the most visible and significant life decisions, and are both the norm and the aspiration of most girls and boys.

This section discusses how norms and prevailing practices around marriage and childbearing are bending, although they are infrequently challenged. As womenâs empowerment grows, they gain more control over their bodies and fertility choices, such as contraceptive use, family size, spacing between births, and the sex composition of their children (Jejeebhoy 1995b; Malhotra, Schuler, and Boender 2002). In turn, these new reproductive behaviors and changes in family formation influence womenâs major life decisions.

The position of women in the household is central to their ability, or lack of it, to exercise their agency, and this position varies with age, the bearing of children, economic participation, and more. Marriage and reproduction have a different effect on menâs lives and agency. For many men, family formation moves them from a subordinated positionâas sons under the authority of an older maleâto the position of power in their own households. But with that power come responsibilities, such as the economic support of the new family and the pressures to comply with associated norms.

One of the messages that emerged from the discussions with young adult women and men in the study is a desire to delay starting a family until they have greater control over their lives. They consider having an education and a job with a steady income, as well as physical and psychological maturity, to be preconditions for a secure adult family life. These yearnings for control, however, constantly interact with social norms and expected behaviors about how and when family formation should begin. Different views on the appropriate age for marriage may have an impact on the accumulation of endowments (e.g., education) and the capacity to take advantage of economic opportunities.

Marriage may free young women from their fatherâs control, but it often is simply a transition into different situations of disadvantage with another male (their husband) and of decreased agency as a junior female among the women in the husbandâs extended family (Kabeer 2001). Arranged marriages are still customary in some of the study communities, as are financial payments, such as a bride price (lobola in southern Africa) or a dowry. In other sample communities, women have to yield to strong pressure from husbands and in-laws over the number of children they bear.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anthropology | Archaeology |

| Philosophy | Politics & Government |

| Social Sciences | Sociology |

| Women's Studies |

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32074)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31469)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31419)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(30795)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(18641)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(14785)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(13797)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(13698)

Fifty Shades Freed by E L James(12924)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(12888)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(12858)

For the Love of Europe by Rick Steves(11554)

Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan(8898)

Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit by John E. Douglas & Mark Olshaker(8718)

The Lost Art of Listening by Michael P. Nichols(7169)

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress by Steven Pinker(6879)

The Four Agreements by Don Miguel Ruiz(6324)

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou(6284)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(5844)