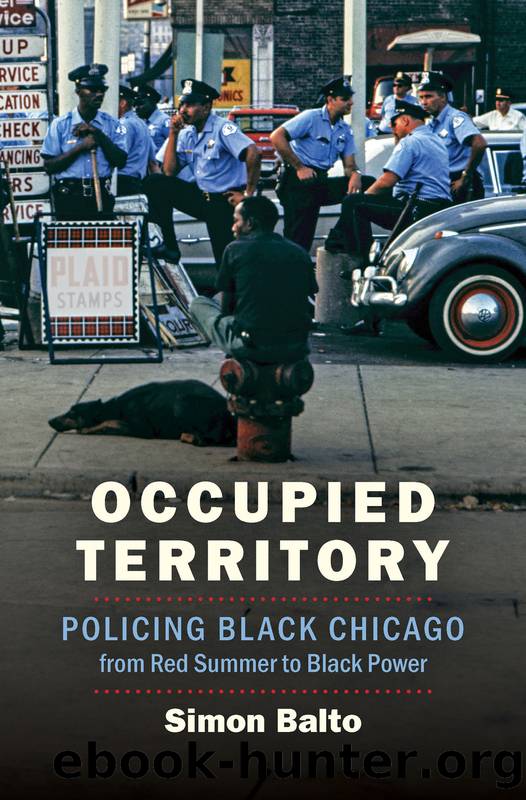

Occupied Territory by Balto Simon;

Author:Balto, Simon;

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: University of North Carolina Press

Published: 2019-07-15T00:00:00+00:00

“Nigger, I Will Kill You”: Race and the Problem of Police Violence

Black Chicagoans had the most to lose when accountability mechanisms failed. The policy of aggressive preventive patrol encouraged officers to view the public with intense suspicion in the neighborhoods where it was implemented; and recognizing the inversion of normative law, citizens remarked that “the police treat suspects as guilty until proven innocent.”79 Aggressive preventive patrol unleashed a police regime premised in hypersurveillance and constant contact with citizens, and the failure of the IID meant that there was no corresponding policy mechanism in place to ensure that expanded power was coupled with expanded accountability.

This was a problem for many reasons, not least of them the fact that police officers’ opinions about black people were demonstrably retrograde by the 1960s. We can see the legacies of racist logics about black criminality in the CPD’s crime forecasts and budget requests, of course, but they were also there in even plainer view. Hard data on racial attitudes is always complicated, and it’s nonexistent for the first part of the 1960s, even though in 1961 the CCHR reported serious “hostile attitudes toward Negroes” among police recruits.80 The picture clarifies later in the decade, however. Working under a federal grant and in coordination with Wilson in Chicago and police heads in Boston and Washington, DC, University of Michigan social scientist Albert Reiss conducted several studies in the mid-1960s on community attitudes toward the police and police attitudes toward the community. The results of the latter were particularly notable. Of the 510 white police officers that Reiss and his colleagues interviewed and observed, 72 percent of them admitted to or displayed attitudes that the researchers characterized as “highly prejudiced, extremely anti-Negro” (38 percent) or “prejudiced, anti-Negro” (34 percent). Meanwhile, of the ninety-four black officers they observed or interviewed, 18 percent also demonstrated some level of disdain for black people.81

Police brutality was the most potent issue on which these questions of racism and accountability collided. As we have seen already, police violence had plagued members of the black community for years, and now, under Wilson, both the power and presence of the police in black neighborhoods were escalating. For community members, that growing power was not only an affront in that it heightened the chances of being stopped and frisked and treated like a criminal; it was also legitimately dangerous when decoupled from meaningful oversight and accountability. If, as Earl Davis put it, the IID was only there to serve as an “eyewash operation,” what hope was there of curtailing police violence?

The answer to the question depended on who you asked. For police officials and their supporters, the fundamental premise of the question was illegitimate. Wilson, crime commission members, and others repeatedly claimed that brutality was either a dead letter or was becoming so.82 In the summer of 1963, for example, CPD officers brutalized civil rights demonstrators when they picketed for better schooling opportunities for black children, drawing criticisms from the black press as conjuring “shadows of Mississippi.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(14768)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(13787)

Underground: A Human History of the Worlds Beneath Our Feet by Will Hunt(11843)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(11800)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(11627)

Wiseguy by Nicholas Pileggi(5323)

American History Stories, Volume III (Yesterday's Classics) by Pratt Mara L(5139)

Perfect Rhythm by Jae(5076)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5024)

Paper Towns by Green John(4805)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(4627)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4557)

The Mayflower and the Pilgrims' New World by Nathaniel Philbrick(4285)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4250)

Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI by David Grann(4192)

Too Much and Not the Mood by Durga Chew-Bose(4097)

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen(4096)

The Borden Murders by Sarah Miller(4025)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(3916)