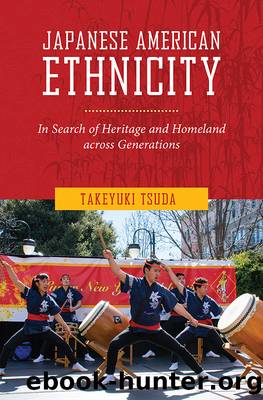

Japanese American Ethnicity by Takeyuki Tsuda

Author:Takeyuki Tsuda [Tsuda, Takeyuki]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: Social Science, Anthropology, Cultural & Social, Ethnic Studies, General

ISBN: 9781479807208

Google: 3gHvCwAAQBAJ

Publisher: NYU Press

Published: 2016-09-13T03:21:27+00:00

The Cultural Essentialization of Japanese Americans

Once Japanese Americans are categorized according to their ethnic origins, they are also essentialized as culturally âJapaneseâ to a certain extent as well. Because of the tendency to conflate race and culture, peoples of Japanese phenotype/descent are seen as inherently connected to their Japanese cultural heritage, even if they were born in the United States and are fully Americanized. âJapan is as foreign of a country to me as Zimbabwe,â one sansei woman remarked. âBut people continue to think Iâm not truly Americanized yet and that somehow, I canât leave my culture behind, that I have some innate connection to Japan.â

Thus, Japanese Americans are often expected to be familiar with the Japanese language and culture (Tuan 2001:78-79) or have a natural affinity with Japan.2 As noted above, my interviewees reported numerous instances of strangers using Japanese words when interacting with them (konnichiwa, domo arigato, sayonara, and so on). This is especially true of Americans who have studied Japanese (or lived in Japan) and are eager to try out their Japanese. Others simply assume Japanese Americans know a lot about Japan and ask them about the country or its culture or talk about their prior experiences in Japan.

Moreover, it is not only majority whites who culturally essentialize Japanese Americans. Japanese immigrants from Japan are among those who most often assume that those who are of Japanese descent are culturally Japanese as well. On numerous occasions when I have gone to Japanese restaurants or stores with Japanese Americans, waiters or staff have spoken Japanese to us. Kate Nishimoto, a sansei who studied Japanese in Japan, has had similar experiences: âWhenever I go to Fujiya [a local Japanese food store], which is regularly, they always speak to me in Japanese. I could answer in Japanese, but I never feel comfortable doing that because I donât use the language. So I usually answer in English.â

Another striking incident occurred in San Diego, when I went to a sushi restaurant with my friend, Cathy, and one of her acquaintances, Ruth, who is an issei who came to the United States when she was a baby and does not speak any Japanese. She is, however, very involved in the Japanese American community and considers herself to be Japanese American. As usual, the Japanese waitress spoke to us in Japanese and continued to do so even when Cathy and Ruth did not respond. Once we were seated at the sushi bar, we entered into a conversation with the Japanese sushi chef, who was a very friendly man, and knew Cathy quite well, since she was a frequent customer. He began speaking to Ruth in Japanese, and when she told him she could not speak Japanese, he gave her a hard time for having forgotten the language. âSo do you only eat hamburgers now? No Japanese food?â he teased her. I was surprised he continued to speak to her mainly in Japanese (despite the fact that he is proficient in English, having lived in the United States since 1972), making Ruth feel inadequate and uncomfortable.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anthropology | Archaeology |

| Philosophy | Politics & Government |

| Social Sciences | Sociology |

| Women's Studies |

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32544)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31940)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31928)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(31915)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19033)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(15942)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14481)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(14050)

For the Love of Europe by Rick Steves(13891)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(13344)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(13343)

Fifty Shades Freed by E L James(13231)

Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit by John E. Douglas & Mark Olshaker(9317)

Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan(9275)

The Lost Art of Listening by Michael P. Nichols(7488)

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress by Steven Pinker(7306)

The Four Agreements by Don Miguel Ruiz(6744)

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou(6610)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6263)