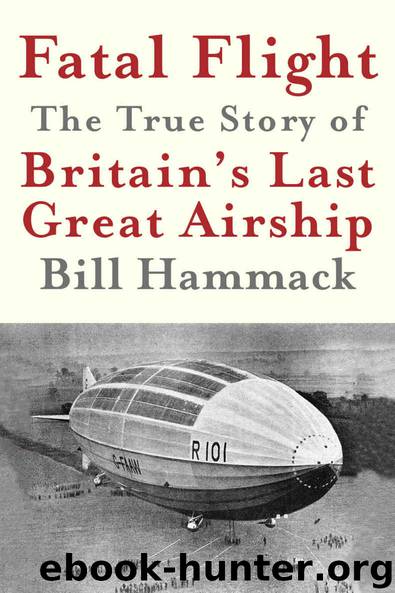

Fatal Flight: The True Story of Britain's Last Great Airship by Bill Hammack

Author:Bill Hammack [Hammack, Bill]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: ENGINEERING / History SCI034000 SCIENCE / History, TEC002000 TECHNOLOGY &, TEC056000 TECHNOLOGY &, ENGINEERING / Aeronautics & Astronautics, HIS015070 HISTORY / Europe / Great Britain / 20th Century

ISBN: 9781945441028

Publisher: Articulate Noise Books

Published: 2017-05-31T22:00:00+00:00

In 1926, Britain’s Director of Civil Aviation hailed R.101 as the “greatest adventure in construction engineering of our time” and, yet, in charge was Vincent Richmond, R.101’s chief designer—a man with no training in engineering and no experience designing any airborne craft. Richmond studied chemistry at the Royal College of Science, and his sole practical experience with airships was in creating the waterproof finish applied to the outer cloth covers of airships and small military balloons. His engineering experience was limited to a short stint, before the First World War, designing docks for S. Pearson and Sons, a large construction firm.

Sometimes Richmond’s decisions shocked his engineering staff. When he ordered the gas bag netting let out to gain more lift, a Works’ engineer noted that this “violated the essential feature of Michael Rope’s careful design.” To make up for Richmond’s sketchy technical training, his staff at the Works had to “balance the gaps in his engineering knowledge,” as a colleague discreetly phrased it; or, as another delicately said, they “supplemented” his technical knowledge.

For example, Harold Roxbee, an engineer at the Works, pointed out to Richmond an error in his design for R.101’s framework: the cross-section of the ship near the tail would not be symmetrical and this would disrupt airflow over the airship. The cigar-shaped framework of all airships arose from a set of rings spaced along a central axis and linked from back to front by long girders. At least twenty of these girders, Roxbee explained to Richmond, were used in all airship designs, but because Richmond designed R.101 with only fifteen girders the cross-section of R.101 as it tapered to its tail lost its symmetrical, nearly circular shape.

Roxbee pleaded with Richmond to increase the number of girders, but Richmond dismissed this suggestion. When R.101’s framework was assembled, the section near the tail was indeed a distorted circle. Roxbee solved the problem by retrofitting—an action never desired by an engineer. He had the girders twisted as they neared the tail to keep the cross-section circular.

After R.101’s crash, the young Roxbee thrived as an aeronautical engineer and his development of the gas-powered turbine for jets earned him a knighthood.

Criticism of Richmond’s R.101 design wasn’t limited to the Works’ staff. Two of the greatest airship engineers of Richmond’s era thought R.101’s framework deficient. Ludwig Dürr, the chief architect for the Zeppelin Company, praised R.101 in public—“I regard R.101 as one of the best airships ever designed and constructed,” he told Richmond a month before the ship’s crash—but in private he expressed reservations about the design. Dürr worried that the ship’s unbraced rings, in contrast to the wire spokes of the zeppelin frame, could never be made light enough. Their weight, he thought, reduced payload and fuel, which hampered R.101’s potential as a commercial vehicle because its range would be far too short. And even more severe was the opinion of Britain’s most experienced airship designer.

Barnes Wallis designed four of R.101’s predecessors: No. 9 in 1916, No. 23 in 1917, No. 26 in 1918, and R.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Room 212 by Kate Stewart(5105)

The Crown by Robert Lacey(4807)

Endurance: Shackleton's Incredible Voyage by Alfred Lansing(4769)

The Iron Duke by The Iron Duke(4349)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(4203)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(4101)

Killing England by Bill O'Reilly(3995)

Say Nothing by Patrick Radden Keefe(3975)

I'll Give You the Sun by Jandy Nelson(3428)

Shadow of Night by Deborah Harkness(3360)

Hitler's Monsters by Eric Kurlander(3328)

Mary, Queen of Scots, and the Murder of Lord Darnley by Alison Weir(3202)

Blood and Sand by Alex Von Tunzelmann(3195)

Eleanor & Park by Rainbow Rowell(3153)

Darkest Hour by Anthony McCarten(3119)

Margaret Thatcher: The Autobiography by Thatcher Margaret(3079)

Book of Life by Deborah Harkness(2931)

Red Famine: Stalin's War on Ukraine by Anne Applebaum(2928)

The One Memory of Flora Banks by Emily Barr(2857)