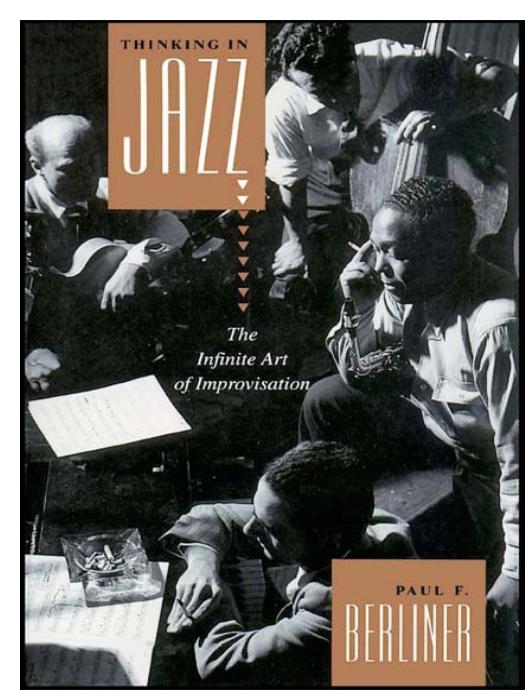

Thinking in Jazz by Berliner Paul F

Author:Berliner, Paul F.

Language: eng

Format: epub, pdf

Publisher: The University of Chicago Press

THIRTEEN

Give and Take

The Collective Conversation and Musical Journey

Usually, everyone takes their cue from the soloist, but anyone could initiate something and we would all follow suit. Buster Williams may play something and I’ll say, “Oh, yeah?” and try to follow him because it makes the group sound more cohesive. It’s a matter of give and take.—Kenny Barron

Musicians discussing the background and knowledge they bring to performances comment often on how much more complex jazz is than it is possible to verbalize in an interview. Clearly, talking about the preparation for collective improvisation is one thing, the actual experience of improvising quite another.1 “No matter what you’re doing or thinking about beforehand;” Chuck Israels explains, “from the very moment the performance begins, you plunge into that world of sounds. It becomes your world instantly, and your whole consciousness changes.”

Despite the difficulties of verbalizing about essentially nonverbal aspects of improvisation, artists favor two metaphors in their own discussions about the subject that provide insight into unique features of their experience. One metaphor likens group improvisation to a conversation that players carry on among themselves in the language of jazz. The second likens the experience of improvising to going on a demanding musical journey. From the performance’s first beat, improvisers enter a rich, constantly changing musical stream of their own creation, a vibrant mix of shimmering cymbal patterns, fragmentary bass lines, luxuriant chords, and surging melodies, all winding in time through the channels of a composition’s general form. Over its course, players are perpetually occupied: they must take in the immediate inventions around them while leading their own performances toward emerging musical images, retaining, for the sake of continuity, the features of a quickly receding trail of sound. They constantly interpret one another’s ideas, anticipating them on the basis of the music’s predetermined harmonic events.

Without warning, however, anyone in the group can suddenly take the music in a direction that defies expectation, requiring the others to make instant decisions as to the development of their own parts. When pausing to consider an option or take a rest, the musician’s impression is of a “great rush of sounds” passing by, and the player must have the presence of mind to track its precise course before adding his or her powers of musical invention to the group’s performance. Every maneuver or response by an improviser leaves its momentary trace in the music. By journey’s end, the group has fashioned a composition anew, an original product of their interaction.

Striking a Groove

Among all the challenges a group faces, one that is extremely subtle yet fundamental to its travels is a feature of group interaction that requires the negotiation of a shared sense of the beat, known, in its most successful realization, as striking a groove.2 Incorporating the connotations of stability, intensity, and swing, the groove provides the basis for “everything to come together in complete accord” (HO). “When you get into that groove;” Charli Persip explains, “you ride right on down that groove with no strain and no pain—you can’t lay back or go forward.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Goal (Off-Campus #4) by Elle Kennedy(13681)

Kathy Andrews Collection by Kathy Andrews(11844)

Diary of a Player by Brad Paisley(7585)

Assassin’s Fate by Robin Hobb(6227)

What Does This Button Do? by Bruce Dickinson(6210)

Big Little Lies by Liane Moriarty(5808)

Altered Sensations by David Pantalony(5107)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(5013)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(4205)

The Death of the Heart by Elizabeth Bowen(3626)

The Heroin Diaries by Nikki Sixx(3554)

Confessions of a Video Vixen by Karrine Steffans(3313)

Beneath These Shadows by Meghan March(3312)

How Music Works by David Byrne(3273)

The Help by Kathryn Stockett(3153)

Jam by Jam (epub)(3096)

Harry Potter 4 - Harry Potter and The Goblet of Fire by J.K.Rowling(3077)

Computational Linguistics and Intelligent Text Processing: 20th International Conference, CICLing 2019 La Rochelle, France, April 7â13, 2019 Revised Selected Papers, Part I by Alexander Gelbukh(2997)

Strange Fascination: David Bowie: The Definitive Story by David Buckley(2874)