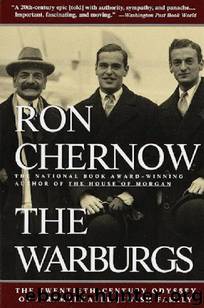

The Warburgs by Ron Chernow

Author:Ron Chernow [Chernow, Ron]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9780307813503

Google: 9RmKXgFmGIEC

Amazon: B006Q1SRFC

Publisher: Vintage

Published: 2012-01-18T00:00:00+00:00

CHAPTER 28

––

Beat the Devil

Once a breezy, fun-loving young man, Max Warburg at sixty-six was far more somber and introspective. In his Kösterberg studio, which resembled an Italian monk’s cell, he dreamed forlornly of reconciling Zionists and non-Zionists, Jews and other Germans. Until this time, he had engaged in philanthropic Judaism, attending High Holy Days at the synagogue, covering the deficit of the Hamburg Jewish community, chairing the Jewish orphanage, and sitting on the board of the Talmud Torah school. Now he hoped to fashion a new Judaism that might transcend divisions and heal a troubled world. It would prove a sad, dispiriting exercise amid the jackbooted madness of 1933.

Writing to philosopher Martin Buber, Max said they needed a Judaism suited to modern times. The question, of course, was where it would be practiced. Still anti-Zionist, Max envisioned Palestine as a sanctuary for persecuted Jews and a seat of Jewish learning, not as a sovereign Jewish state. But even as Palestine loomed somewhat larger in his vision, he tried to devise new syntheses of German and Jewish culture. While German Jews should support Palestine, he said, they mustn’t lessen their devotion to the Fatherland.1

From the time Hitler seized power, Max was of two minds and led a schizoid existence. One side of him exhorted Jews to stay and fight, accusing those who left of cowardice. This same man, however, was pivotal in many schemes to promote a Jewish exodus. He tried to develop a new set of reflexes without discarding the old ones and never escaped this contradiction. In many ways, Jewish financiers were the least well suited to deal with the situation, not only because they bore the brunt of much Nazi propaganda, but because they had long reposed their trust in the state and couldn’t adjust to an adversarial situation.

If Max emerged as central to emigration schemes, it was because money was often the major snag for Jews hoping to flee. Many countries asked for financial guarantees before receiving Jews, which was a considerable hurdle because of German exchange controls. In 1931, the Brüning government had imposed a 25 percent flight tax on capital shifted abroad and under the Nazis, these extortionate taxes steadily rose, making the decision to leave excruciating. As private bankers, the Warburgs could sometimes offer means to help Jews extricate money from Germany.

After 1932, German citizens could only convert blocked marks into other currencies at a steep discount that would skim off 96 percent of the amount in question by the end of the decade. Jewish leaders racked their brains for ways to secure more favorable exchange rates. At this point, the Nazis were encouraging a Jewish exodus, which they thought might spread anti-Semitism abroad, especially if the refugees were poor. They also sought ways to counter the worldwide Jewish boycott of German goods and boost exports. The upshot was the so-called Haavara agreement (haavara means “transfer” in Hebrew) of August 1933, negotiated between Palestine Jews, backed by the Jewish Agency, and the Nazi government. In the end, this devil’s pact may have spared fifty-two thousand Jewish souls from the crematoria.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| American Revolution | Civil War |

| US Presidents |

Fanny Burney by Claire Harman(25790)

Empire of the Sikhs by Patwant Singh(22183)

Out of India by Michael Foss(16313)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(11914)

Small Great Things by Jodi Picoult(6106)

The Six Wives Of Henry VIII (WOMEN IN HISTORY) by Fraser Antonia(4797)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(4427)

The Lonely City by Olivia Laing(4122)

The Crown by Robert Lacey(4112)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4038)

The Iron Duke by The Iron Duke(3649)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(3574)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(3456)

Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors by Piers Paul Read(3318)

Papillon (English) by Henri Charrière(3277)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(3264)

Stalin by Stephen Kotkin(3089)

Aleister Crowley: The Biography by Tobias Churton(3025)

Ants Among Elephants by Sujatha Gidla(2928)