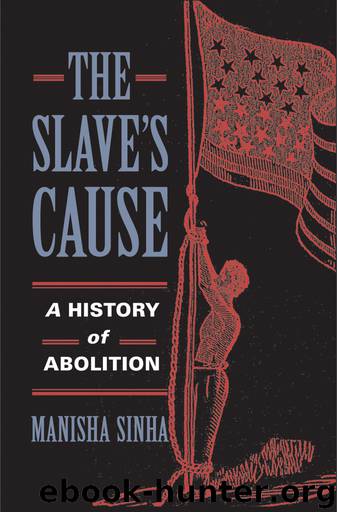

The Slave's Cause by Sinha Manisha

Author:Sinha, Manisha [Sinha, Manisha]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Yale University Press

Published: 2015-09-26T04:00:00+00:00

13

FUGITIVE SLAVE ABOLITIONISM

On February 24, 1844, the Liberator printed an admiring report on Frederick Douglass’s “masterly and impressive” speech in Concord, New Hampshire. The fugitive slave was the master of his audience. Douglass, the writer fantasized, was like “Toussaint among the plantations of Haiti. . . . He was an insurgent slave, taking hold of the right of speech, and charging on his tyrants the bondage of his race.”1 In the two decades before the Civil War, a new generation of black abolitionists, most of them fugitive slaves, came to dominate the movement.

The narratives of fugitive slaves, their firsthand indictment of slavery, was an effective rebuttal to the growing sophistication of the proslavery argument in the antebellum period. Small wonder that slavery ideologues challenged their veracity and dismissed them as abolitionist propaganda. Scholars have also been too quick to ascribe to white editors and amanuenses the abolitionist content of slave narratives.2 Fugitive slaves created an authentic, original, and independent critique of slaveholding, one which made their narratives potent antislavery material. No longer could slaveholders claim that their northern critics had no idea about the actual conditions of southern slaves. Their stories of family separations, torture, abuse of children and women, and the hypocrisy of slaveholders constituted the most compelling answer yet to proslavery ideology. Fugitive slaves were abolitionists in their own right. Their narratives and public careers as spokesmen and women against slavery shaped the abolition movement.

SLAVE NARRATIVES

Slave narratives were the movement literature of abolition. Abolitionists did not simply use or co-opt insurgent slaves, a popular and racialist interpretation that portrays these extraordinary men and women as perpetual victims incapable of political and intellectual warfare against slavery. Fugitive slaves wrote themselves not just into being but also into history. They were engaged in a political struggle against slavery and racism, writing direct rebuttals of slaveholder paternalism, at times as letters to their erstwhile masters.3 Art and politics fused to making a compelling case for black freedom.

People of African descent wrote autobiographies from the early days of racial slavery. Fugitive slave narratives published under abolitionists’ auspices, however, constitute a distinct genre. In the 1820s former slaves such as Solomon Bayley and William Grimes published their narratives. Bayley’s narrative was published in London by Robert Hunard, who hoped it would lead to abolition in the West Indies and the United States. While Bayley’s narrative reads like a spiritual story reinforced by the tragic deaths of his children, he indicts slavery by retelling the story of his “Guinea” grandmother and mother, who were held by a cruel family and whose children were illegally sold. Even more than Bayley, Grimes showed slavery to be an unending catalogue of horrors. Published first in New York in 1825, the work, for which he obtained a copyright, was republished in 1855 with a new conclusion. Grimes describes his checkered life of freedom in Connecticut and his constant fear of being recaptured. In the conclusion he delivers a damning critique of slaveholding republicanism: “If it were not for

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32536)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31933)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31925)

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(19017)

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari(14356)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13303)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12011)

Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari(5358)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(5207)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(5084)

Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow by Yuval Noah Harari(4894)

Endurance: Shackleton's Incredible Voyage by Alfred Lansing(4749)

Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl(4562)

The Silk Roads by Peter Frankopan(4520)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(4456)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(4193)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(4090)

The Motorcycle Diaries by Ernesto Che Guevara(4080)

Stalin by Stephen Kotkin(3949)