The Invisible Sex: Uncovering the True Roles of Women in Prehistory by J. M. Adovasio & Olga Soffer & Jake Page

Author:J. M. Adovasio & Olga Soffer & Jake Page [Adovasio, J. M.]

Language: eng

Format: azw3

Publisher: HarperCollins

Published: 2009-10-13T04:00:00+00:00

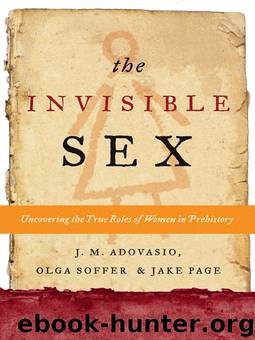

Figure 7-2.

Bracelets and beads made of ivory from the Upper Paleolithic site of Mezin, Ukraine.

COURTESY O. SOFFER

Even in the face of these finds and others that show potential signs of symbolic thought well before it exploded in the Late Paleolithic, it is possible to say the scholarly version of “so what?” Just because one person or group made a set of beads 75,000 years ago doesn’t prove much. It doesn’t show that people in general were making beads back then in order to communicate some sense of identity or status. Sure, people had the capacity to make beads, and to scratch little geometrical figures on pieces of ochre and a few other little “artistic” efforts. The important thing is regular or systematic performance: did most people do it? Was it common behavior? Was it the way the human species of the time confronted the world? One woman making herself a set of beads (which, one needs to remember, entailed also the making of some kind of string on which to place them) is nothing at all like the tremendous flowering of imagery, complex tools, rudimentary architecture, and other skills and achievements that are found in Europe beginning around 45,000 years ago and really hitting stride about 35,000 years ago. On the other hand, we don’t know how widespread bead making might have been in these more ancient times. Being biological items, they don’t preserve all that well.

Many archaeologists studying this period still focus on the grand inventory of objects now in museum and university collections, and on new material coming out of the ground, in order to answer the question, what happened during this immensely important transition? The problem with such kitchen lists based on artifactual evidence that suggests particular behaviors is that the behaviors are not universal—they are local or regional and not at all synchronous. For example, some people in Europe created the amazing cave paintings in places like Chauvet some 30,000 years ago, and soon thereafter equally modern humans moved into North America, where imagery on such a scale never occurred. (But how important is scale? South Americans were producing rock art—or call it rock imagery—10,500 years ago.) In any event, the Europeans of the Late Pleistocene certainly perceived the paintings and also the expansions of range as somehow the means of improving their chances for success in the natural world or the social world, or both. But what (if anything) was universally applicable? Some archaeologists are stepping beyond the normal path of the archaeologist to ask not what happened but why the changes occurred. In this regard, it is helpful to look at the Neanderthals as well as the anatomically and behaviorally modern humans and see how the two human species (or as some others would have it, subspecies) confronted the worlds they found themselves in.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32549)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31948)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31932)

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(19058)

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari(14371)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13319)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12019)

Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari(5366)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(5216)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(5092)

Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow by Yuval Noah Harari(4909)

Endurance: Shackleton's Incredible Voyage by Alfred Lansing(4770)

Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl(4586)

The Silk Roads by Peter Frankopan(4526)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(4469)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(4204)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(4103)

The Motorcycle Diaries by Ernesto Che Guevara(4090)

Stalin by Stephen Kotkin(3959)