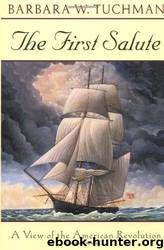

The First Salute by Barbara Wertheim Tuchman

Author:Barbara Wertheim Tuchman

Language: eng

Format: mobi

Tags: Revolutionary, United States, 1775-1783 - Naval Operations, United States - History - Revolution, General, North America, Revolutionary Period (1775-1800), 1775-1783 - Campaigns, History

ISBN: 9780345336675

Publisher: Ballantine Books

Published: 1989-09-06T00:00:00+00:00

X

“A Successful Battle May Give Us America”

IF THE FRENCH did not recognize the significance to themselves of what they were doing in aiding the rebels, neither did the British as a whole consider what place their conflict with the American Colonies had or would have in history. They thought of it simply as an uprising of colonial ingrates which had to be put down by force. To those with a larger world view, it was an imperial power struggle against France.

Ideologically, in the eternal struggle of left and right, the rebellion was seen as subversive of the social order, and the Americans as “levelers” whose example, if successful, would set alight revolutionary movements in Ireland and elsewhere. The British government and its partisans, as opposed to Whigs and radicals, felt themselves to be the upholders of right and privilege who should be receiving Europe’s support instead of hostility in their fight for existence. With France and Spain as enemies and Holland about to be another, and with the prospect of the Neutrality League contesting sovereignty of the seas, Europe in not coming to Britain’s aid, or in actively aiding the Americans, was seen as cutting her own throat; if the Americans won, she would herself experience the tramp of radicals and hear the shout of “Liberty!” across her lands.

Of all people, the somnolent Prime Minister Lord North, who was always begging the King to let him resign because he felt inadequate to the situation, perceived the historical context of the conflict in which his country and its colonies were engaged, and the historical consequences of an American victory. “If America should grow into a separate empire, it must cause,” he foresaw, “a revolution in the political system of the world, and if Europe did not support Britain now, it would one day find itself ruled by America imbued with democratic fanaticism.”

The mutinies and privations of Mr. Washington’s army (the British could not bring themselves to accord him the title of “general”) offered a gleam of hope that the American Revolution was lagging, as could be seen in its want not only of material and finances but of fresh recruits. Encouraged, Clinton told himself comfortably, “I have all to hope and Washington all to fear.” Logically he was right, but a detached observer would have drawn no encouragement, for “hope” to Clinton meant further reason not to act, and “fear” for Washington meant a factor that existed to be overcome.

So certain were British managers of the war in their superiority of force that they remained convinced the rebels would have to give in and make peace. As Lord Germain, the King’s chief adviser, expressed it, “So contemptible is the rebel force now in all parts … so vast is our superiority that no resistance on their part can obstruct a speedy suppression of the rebellion.” Settled complacency allowed no other thought. Expectation of the rebels’ early collapse was all the more intense because it was sorely needed—for despite complacency, British resources were badly strained; recruiting was poor, victualing inadequate and finances on stony ground.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| African Americans | Civil War |

| Colonial Period | Immigrants |

| Revolution & Founding | State & Local |

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(13856)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(12923)

Underground: A Human History of the Worlds Beneath Our Feet by Will Hunt(11251)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(11034)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(10902)

American History Stories, Volume III (Yesterday's Classics) by Pratt Mara L(4821)

Perfect Rhythm by Jae(4616)

Wiseguy by Nicholas Pileggi(4582)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(4337)

Paper Towns by Green John(4164)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4026)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(3996)

The Mayflower and the Pilgrims' New World by Nathaniel Philbrick(3906)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(3725)

Too Much and Not the Mood by Durga Chew-Bose(3689)

Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI by David Grann(3605)

The Borden Murders by Sarah Miller(3581)

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen(3467)

Killing England by Bill O'Reilly(3449)