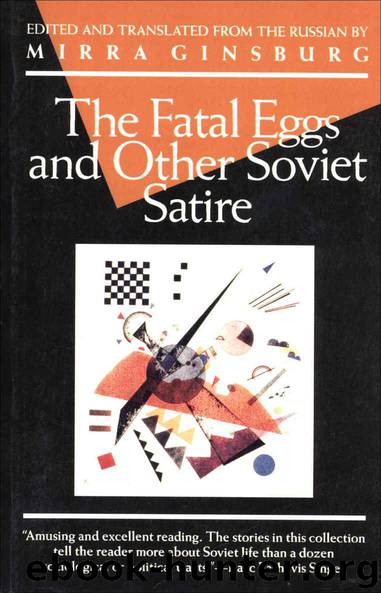

The Fatal Eggs and Other Soviet Satire (Evergreen Book) by Mikhail Bulgakov

Author:Mikhail Bulgakov [Bulgakov, Mikhail]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

Published: 2007-12-01T06:00:00+00:00

Boris Lavrenyov (1891-1962)

Lavrenyov’s early work alternated between the romantic and the humorous. His stories and novels, skillfully told, dealt with contemporary experience. He was also the author of a number of plays, including The Voice of America. “The Heavenly Cap” is a witty grotesque developed against the background of the hungry days of War Communism and the fantastic prosperity of the New Economic Policy (NEP).

The Heavenly Cap

by Boris Lavrenyov

CHAPTER 1

The residents of the houses on the right side of Bolshaya Monet-naya Street kept track of the flow of revolutionary time by the professor of experimental physiology, Alexander Yevlampievich Blagosvetlov. But then, of course, in order to avert a possible accusation of partiality, the author must record that the residents of the left side did likewise.

It was during that unique, romantic time when the cities of the Republic, swept by gunpowder storms, were experiencing the initial period of general impoverishment, and all the clocks and watches, which had until then peacefully ticked away in the living rooms and on the spleens of their owners, had, in obedience to the laws of economics, been swallowed up by the villages.

In exchange for the watches, their owners received starchy and fatty substances. As for the timepieces, they were not infrequently hung around the necks of year-old citizens of peasant origin instead of rattles.

To the villages, the years described here were a period of primary accumulation.

But let us forget the villages. Although the exigencies of the day require assiduous courting of the mysterious elemental forces of the village, the author, steeped in the culture of cities, chooses an urban subject.

In those unforgettable days, city residents were engaged in the sole and universally obligatory occupation of government service.

Refusal to serve verged on treason to the homeland. Therefore everybody was in civil service—even the half-blind, even cripples, not only physical, but also moral—and the state, solicitous for the equal happiness of all its subjects, found work for each, according to his talents, for the six hours a day prescribed by the labor law.

Consequently, every socially conscious citizen was concerned with the question of time, since time, untouched by the general reevaluation of the universe, continued to be divided into hours, and among those hours was the one that marked the official beginning of work. And it was essential to determine this hour, at least with approximate correctness, if one was not to lose his minimum of calories or change his residence for another, as lacking in comforts as his own domicile, but substantially more restrictive of his freedom of movement.

Telling time, however, had become extremely difficult in the absence of the instruments evolved through centuries of scientific practice. It is true that there were individuals who somehow managed to do it. Whenever Aronchik Bleibas, the nephew of the watchmaker from Ertelev Lane, was asked, “What time is it?” he closed his eyes, sniffed with his narrow, always wet-tipped nose, and named a figure. Verification of such experiments by the clock on the City Hall tower proved that

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Spell It Out by David Crystal(36085)

Professional Troublemaker by Luvvie Ajayi Jones(29622)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19003)

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(18947)

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(15258)

The Goal (Off-Campus #4) by Elle Kennedy(13605)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(12166)

The Break by Marian Keyes(9336)

Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan(9223)

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(8892)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(8846)

Educated by Tara Westover(8001)

The handmaid's tale by Margaret Atwood(7706)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(7252)

Win Bigly by Scott Adams(7139)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(6833)

The Rosie Project by Graeme Simsion(6294)

Six Wakes by Mur Lafferty(6198)

The Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual Enlightenment by Eckhart Tolle(5680)