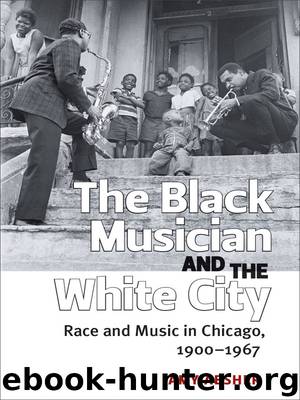

The Black Musician and the White City: Race and Music in Chicago, 1900–1967 by Absher Amy

Author:Absher, Amy

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: The University of Michigan Press

Published: 2018-05-15T00:00:00+00:00

This cautionary statement concerning the use of the charts is interesting because it sought to distance the editors of Billboard from the playing of questionable music and place responsibility on the radio stations. However, the editors failed to note their own role in promoting music. When a song placed significantly on the top-twenty list, it then attracted the ire of the censorship movement. Writing the song, performing the song, and recording the song did not violate the public good. Under the Billboard Page 105 → and Variety arguments, the songs only endangered the public upon broadcasting—either on the radio or jukeboxes. In addition, the editors of Billboard saw the necessity for banning rhythm and blues, but did not discuss the questionable lyrics in the pop and country-and-western musical genres, which the executives of Apollo, Savoy, and Atlantic Records all noted as containing sexual content.

Though Variety and Billboard dominated coverage of the music industry, there were smaller publications defending the positions of niche markets. An example of the smaller publications is the Cash Box—a biweekly paper reporting on the jukebox industry. In September 1954, the Cash Box warned its subscribers of the problems that “dirty” rhythm and blues recordings could cause for the industry if cities and towns were to establish censorship boards. Its editors predicted that the music would be blamed for the rise in juvenile delinquency, and all evidence of “ameliorating delinquency conditions” would be ignored. The looming threat of censorship, which reformists justified by citing rising rates of juvenile delinquency manifested through violence at music shows, would hurt the entire jukebox industry, according to the editors. To survive, the Cash Box suggested that the industry censor itself.23

Audiences accessed the music through unregulated jukeboxes. Owners of the machines filled the jukeboxes with rhythm and blues music because the recordings were cheap and jukebox music did not need to be registered, thus bypassing BMI (Broadcast Music Incorporated) and the ASCAP's (American Society of Composers, Authors, and Programmers) standards boards, which were the organizations that licensed music releases. On the surface, censoring jukeboxes appears to be a separate issue from the banning of music from the radio and from exportation. After all, Variety's editors clearly said, they wanted to protect the “kids,” and jukeboxes represented the much-maligned “saloon” or “barrelhouse” trade. One would imagine that few children were present in saloons to hear the questionable music. Nevertheless, in controlling the jukeboxes, the leaders of the major recording corporations saw a way of controlling the kind of music that reached a wide audience and of curtailing the success of the small labels.

The fight against jukeboxes began in earnest in 1953, when six counties in South Carolina outlawed the machines, and continued into 1954, when police departments across America began to seize the machines and fine their owners. While economic competition motivated the larger recording companies’ support of restrictions on jukeboxes, morality standards Page 106 → and racism motivated community-based opposition. In Chicago, a judge ruled that organized crime controlled jukeboxes and thus that the machines were a detriment to the community.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Goal (Off-Campus #4) by Elle Kennedy(13657)

Kathy Andrews Collection by Kathy Andrews(11812)

Diary of a Player by Brad Paisley(7564)

Assassin’s Fate by Robin Hobb(6200)

What Does This Button Do? by Bruce Dickinson(6195)

Big Little Lies by Liane Moriarty(5790)

Altered Sensations by David Pantalony(5094)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(4996)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(4188)

The Death of the Heart by Elizabeth Bowen(3610)

The Heroin Diaries by Nikki Sixx(3543)

Confessions of a Video Vixen by Karrine Steffans(3301)

Beneath These Shadows by Meghan March(3300)

How Music Works by David Byrne(3261)

The Help by Kathryn Stockett(3139)

Jam by Jam (epub)(3073)

Harry Potter 4 - Harry Potter and The Goblet of Fire by J.K.Rowling(3061)

Computational Linguistics and Intelligent Text Processing: 20th International Conference, CICLing 2019 La Rochelle, France, April 7â13, 2019 Revised Selected Papers, Part I by Alexander Gelbukh(2989)

Strange Fascination: David Bowie: The Definitive Story by David Buckley(2863)