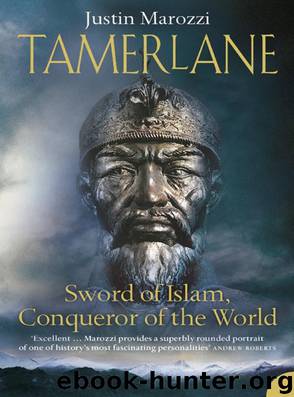

Tamerlane by Justin Marozzi

Author:Justin Marozzi [Justin Marozzi]

Language: eng

Format: epub, mobi

ISBN: 9780007369737

Publisher: HarperCollins

If the Bibi Khanum Mosque was Temur’s most extravagant religious building in Samarkand, the mausolea of Shah-i-Zinda (the Living King) was his holiest. The site itself, which lay beyond the city walls in the north-east of the capital over the ancient settlement of Afrosiab, predated Temur by several centuries, but under the conqueror’s lavish patronage it developed into an important centre for pilgrims, an integral part of his attempt to make Samarkand the Mecca of Central Asia.

Mausolea had existed here from at least the twelfth century, but Genghis’s hordes erased them from the face of the earth, with one prominent exception. The solitary survivor of the Mongol invasion and the centrepiece of the complex was the tomb of Kussam ibn Abbas, cousin of the Prophet Mohammed, who is supposed to have arrived in the province of Sogdiana – which included Samarkand and Bukhara – in 676. Brimming with missionary fervour, Kussam was on a mission to convert the Zoroastrian fire-worshippers to Islam. The local population did not take kindly to this foreign preacher, however, and Kussam was promptly beheaded. Notwithstanding his decapitation, the story goes, he managed to pick up his head and jump down a well, where he has remained ever since, ready to resume his reign when the time comes. The Arabs venerated him as a great martyr, and the cult of the Living King was born. Over the centuries, the tomb continued to attract the faithful. ‘The inhabitants of Samarkand come out to visit it every Sunday and Thursday night,’ wrote Ibn Battutah in 1333. ‘The Tatars also come to visit it, pay vows to it and bring cows, sheep, dirhams and dinars; all this is used for the benefit of the hospital and the blessed tomb.’

Temur sought to increase the popularity and prestige of the Shah-i-Zinda by converting it into a royal burial ground. Valiant amirs were also allowed to be buried here, and during the latter half of the fourteenth century the complex developed into one of the prize jewels in Samarkand’s architectural crown. Two of Temur’s sisters were buried there, together with other relatives and amirs who had loyally served him. It was a feast of fine craftsmanship, masonry, calligraphy and art, a street of the dead awash with all hues of blue majolica tiles. Blue domes glowed like beacons in the white light, while all around them plainer domes of terracotta baked slowly in the sun.

For most of the twentieth century, in a cruel twist of history perpetrated by the Soviets, Shah-i-Zinda languished as an anti-Islamic museum. Now freed from the shackles of communism it is enjoying its latest renaissance as one of Samarkand’s most impressive attractions. One afternoon, Farkhad and I took a taxi to the necropolis. Our driver, a retired army officer, was completely unmoved by the government’s rehabilitation of Temur: ‘You know, in the army now they teach soldiers about Temur, how he was a great warrior, how he won his many battles and how the new army of Uzbekistan fights in his spirit.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Asia |

| Canadian | Europe |

| Holocaust | Latin America |

| Middle East | United States |

Fanny Burney by Claire Harman(26597)

Empire of the Sikhs by Patwant Singh(23074)

Out of India by Michael Foss(16849)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13319)

Small Great Things by Jodi Picoult(7122)

The Six Wives Of Henry VIII (WOMEN IN HISTORY) by Fraser Antonia(5505)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(5092)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4954)

The Crown by Robert Lacey(4807)

The Lonely City by Olivia Laing(4799)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(4469)

The Iron Duke by The Iron Duke(4349)

Papillon (English) by Henri Charrière(4263)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(4188)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(4101)

Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors by Piers Paul Read(4023)

Stalin by Stephen Kotkin(3957)

Aleister Crowley: The Biography by Tobias Churton(3634)

Ants Among Elephants by Sujatha Gidla(3463)