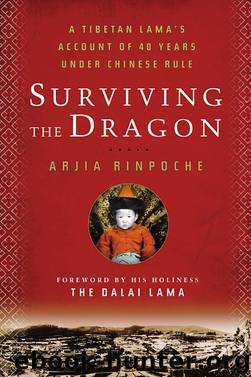

Surviving the Dragon by Arjia Rinpoche

Author:Arjia Rinpoche [Arjia Rinpoche]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9781605291628

Publisher: Potter/Ten Speed/Harmony/Rodale

Published: 2010-02-27T16:00:00+00:00

Not all of my Chinese friends had hidden agendas. Because Zhang Xueyi was a doctor, we called him Zhang Menpa (menpa meaning “doctor” in Tibetan). Zhang Menpa was a man of extreme integrity. He had been imprisoned twice, once for protecting his friends. He had paid a high price for his loyalty and devotion: 20 years in prison.

I met Zhang Menpa for the first time in 1965 during a campaign to cleanse the Party of corruption before the Cultural Revolution. That day Serdok Rinpoche and I had gone to visit Gyayak Rinpoche in his rooms. Upon entering, we noticed a man dressed in the navy blue Mao suit worn by Party cadres, sitting on the edge of Gyayak Rinpoche’s platform. He had a ruddy complexion and facial features typical of local Chinese. We assumed he was a government official, so we meekly seated ourselves and kept our eyes averted, regretting having come to visit. But Gyayak Rinpoche—relaxed and playful—did not seem to mind this government official at all.

Gyayak Rinpoche explained, “This is Zhang Menpa. He is one of us. Don’t be afraid.” We answered, “Yes, yes,” but secretly we remained distrustful. Zhang Menpa was a little embarrassed, too, and, after offering some excuse, left shortly thereafter. After his departure, Gyayak Rinpoche gave us a brief history of Zhang Menpa. His father was a famous veterinarian who had tended sick horses at our monastery in prerevolutionary days. The senior Mr. Zhang had sent his son away to become a medical doctor. In the 1950s, the young Dr. Zhang was imprisoned because he had his own office and was considered a capitalist.

He was supporting himself with a small business. At the time all trading was banned, and small businessmen were considered opportunists or bourgeois exploiters. The Communists accused Zhang Menpa of secretly purchasing a batch of Tibetan jewelry, such as traditional hair clasps for women, made of silver, turquoise, and coral. Trading was illegal, and so were crafts such as silversmithing and jewelry making. Their production was referred to as “business in underground factories.”

After catching the unlucky Zhang on the outskirts of the nomad village where he had made his purchase, soldiers attempted to turn him into an informer for infiltrating the underground factories. The loyal Zhang refused to name any of the jewelry makers from whom he had purchased goods, despite being tortured. His home and property, with all its contents, were confiscated as a result of his refusal to cooperate.

While in jail, Zhang not only took care of ailing inmates, but was also diligent in pursuing knowledge for his own benefit. He became acquainted with a high Tibetan lama in prison and under his tutelage studied Buddhism. He soon became a dedicated practitioner, and after being released from prison continued instruction with Gyayak Rinpoche, under the pretext that he was visiting a patient. As Gyayak Rinpoche finished telling us this story, our doubts about Zhang dissipated. As we got to know him better, our admiration grew.

One day, Zhang Menpa invited me to his house, where I met his wife and two sons.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| African-American & Black | Australian |

| Chinese | Hispanic & Latino |

| Irish | Japanese |

| Jewish | Native American & Aboriginal |

| Scandinavian |

Becoming by Michelle Obama(9314)

The Last Black Unicorn by Tiffany Haddish(5094)

Beartown by Fredrik Backman(4464)

Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl(3674)

The Book of Joy by Dalai Lama(3258)

In a Sunburned Country by Bill Bryson(2964)

The Choice by Edith Eva Eger(2909)

The Five People You Meet in Heaven by Mitch Albom(2861)

Full Circle by Michael Palin(2793)

The Mamba Mentality by Kobe Bryant(2685)

The Social Psychology of Inequality by Unknown(2333)

Book of Life by Deborah Harkness(2297)

The Checklist Manifesto by Atul Gawande(2222)

Less by Andrew Sean Greer(2209)

The Big Twitch by Sean Dooley(2052)

No Room for Small Dreams by Shimon Peres(1997)

No Ashes in the Fire by Darnell L Moore(1992)

A Burst of Light by Audre Lorde(1988)

Imagine Me by Tahereh Mafi(1977)