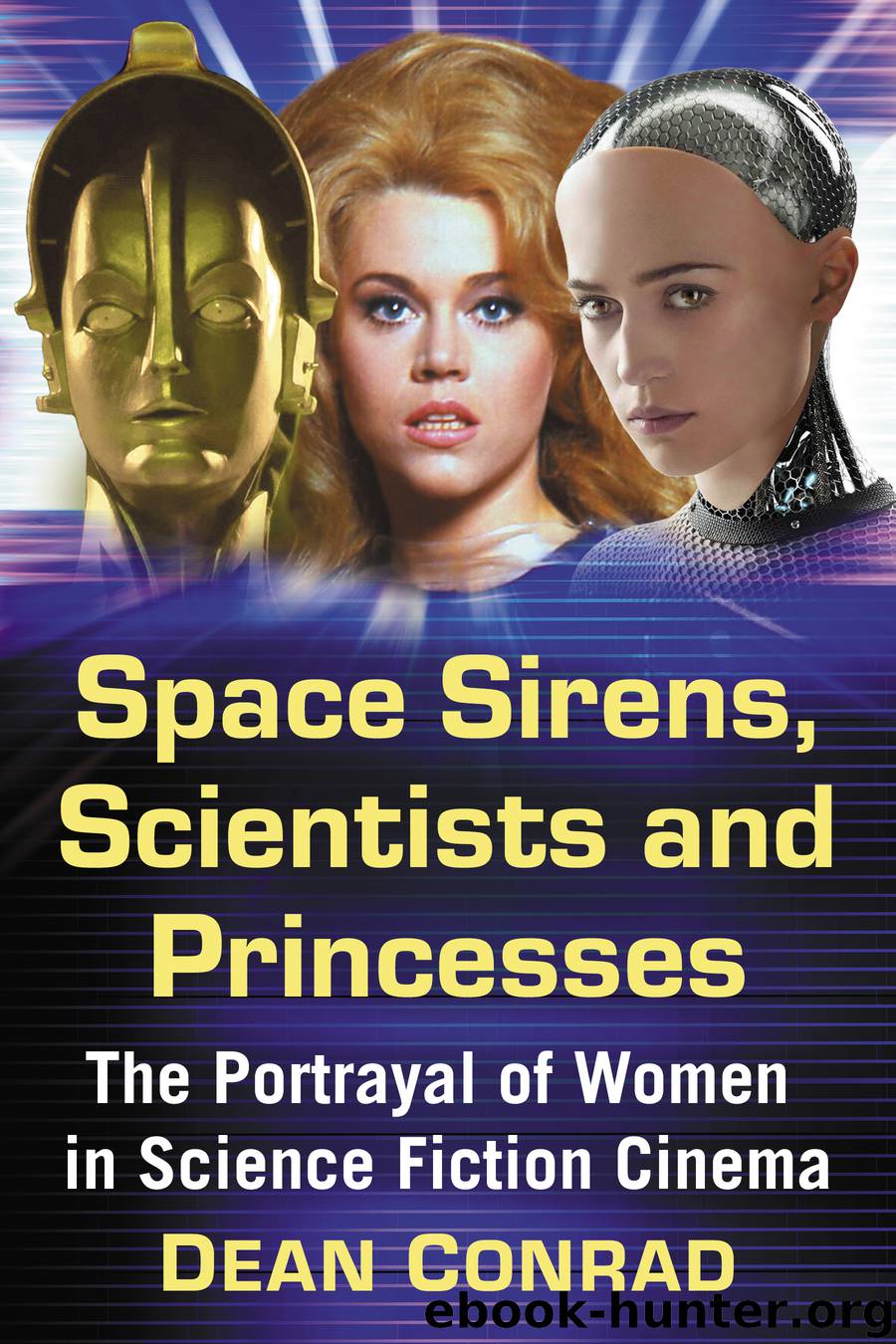

Space Sirens, Scientists and Princesses by Dean Conrad

Author:Dean Conrad

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: McFarland

Published: 2018-06-05T16:00:00+00:00

RIPLEY: Did what?

CALL: It’s like killing your own kind.

RIPLEY: It was in my way.

Ripley’s offhand response—one of many throughout the film—hardens her in much the same way that Sarah Connor was hardened for Terminator 2: Judgment Day in 1991. With fewer nuances and a shallower character crucible to dip into, Weaver’s role, rather than deepening psychologically, soon begins to hemorrhage viewer sympathy. This is transferred to Call, who eventually usurps Ripley as the film’s most effective point of emotional contact. Part way through the film, Call is revealed to be a gynoid—a female robot—designed to serve humans with unquestioning loyalty; as such, she is crucial to Alien: Resurrection’s next feminist message: that of injustice repaid.

Repayment comes in a sequence in which Call takes control of the spaceship computer, which, for Whedon and Jeunet’s film is, perhaps predictably, called “Father,” rather than “Mother.” The change of gender enables the filmmakers to set up an ironic twist. Call locks an escape door against the malevolent male scientist, Wren, who then cries out to the computer, “Father? FATHER!” The sequence inverts Ripley’s own exasperated cry of “MOTHER!” to the computer towards the end of the original Alien film in 1979; it also reflects Christ’s cry to his own father as he suffered on the cross. The female outsider’s response to the male establishment figure comes when Call addresses Wren through the ship’s feedback speakers: “Father’s dead, asshole.”

It is another potentially powerful and empowering moment. However, once again, it is weakened by the screenplay’s sustained mockery of the same feminist sensibilities that had given succor to Weaver and Ripley eighteen years earlier. For example, when Call is unable to communicate remotely with the spaceship, her excuse is witty and played for laughs: “I burned my modem, we all did.” This thinly veiled reference to the myth of the bra-burning radical feminist33—along with many similar lines of dialogue—signals a pendulum-swing back to the open-season on outspoken women that had characterized the suffragist films of the silent period, as discussed in Chapter I.

And so it goes. Alien: Resurrection is loaded with witty, ironic and comic lines, but they do not come naturally, as they had done in the light comedy Back to the Future; instead, they clash with other themes, making it difficult to discern what the screenwriter is trying to do or say. This fourth film is so overloaded that the serious gets lost in the frivolous, and vice versa. The challenge to patriarchy through the parthenogenetic mother or the potential lesbian relationship between Ripley and Call work on one level, but these deepening relationships with the alien and the alienated are regularly diluted by the antics of the other characters, who are largely ciphers and comic turns. Alien: Resurrection works on many levels, but not all together.

The starkest example of this is a sequence, described by Eaton as “the omphalic centre of the picture….”34 The critic’s choice of the word “omphalic”—relating to the navel and umbilical—is apt in many ways. This is the sequence

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini(4435)

Gerald's Game by Stephen King(3918)

The Perils of Being Moderately Famous by Soha Ali Khan(3782)

Dialogue by Robert McKee(3582)

Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting by Robert McKee(2986)

The 101 Dalmatians by Dodie Smith(2936)

The Pixar Touch by David A. Price(2740)

Confessions of a Video Vixen by Karrine Steffans(2675)

Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald by J. K. Rowling(2543)

How Music Works by David Byrne(2526)

Slugfest by Reed Tucker(2416)

Harry Potter 4 - Harry Potter and The Goblet of Fire by J.K.Rowling(2416)

The Mental Game of Writing: How to Overcome Obstacles, Stay Creative and Productive, and Free Your Mind for Success by James Scott Bell(2393)

Wildflower by Drew Barrymore(2118)

Scandals of Classic Hollywood: Sex, Deviance, and Drama from the Golden Age of American Cinema by Anne Helen Petersen(2109)

Casting Might-Have-Beens: A Film by Film Directory of Actors Considered for Roles Given to Others by Mell Eila(2071)

Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting by Syd Field(2057)

Robin by Dave Itzkoff(2005)

The Complete H. P. Lovecraft Reader by H.P. Lovecraft(1977)