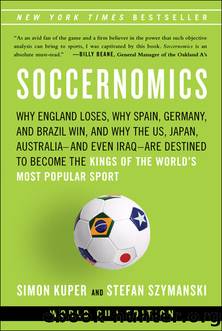

Soccernomics (World Cup Edition) by Simon Kuper & Stefan Szymanski

Author:Simon Kuper & Stefan Szymanski [Kuper, Simon & Szymanski, Stefan]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: Business Aspects, Football, Non-Fiction, Soccer, Sociology of Sports, Sports & Recreation, World Cup

ISBN: 9781568584805

Google: ijVnAgAAQBAJ

Amazon: 1568584814

Publisher: Nation Books

Published: 2014-04-21T23:00:00+00:00

WHY DAVID BEAT GOLIATH

Strangely, it was the British fanzine When Saturday Comes that best expressed the joys of an unbalanced league. WSC is, in large part, the journal of small clubs. It publishes moving and funny pieces by fans of minnows like Crewe or Swansea. Few of its readers have much sympathy with Manchester United (though some, inevitably, are United fans). Many of WSC’s writers have argued for a fairer league. Yet in September 2008 Ian Plenderleith, a contributor living outside Washington, DC, argued in WSC that America’s MLS, in which “all teams started equal, with the same squad size, and the same amount of money to spread among its players’ wages,” was boring. The reason: “No truly memorable teams have the space to develop.” The “MLS is crying out for a couple of big, successful teams,” Plenderleith admitted. “Teams you can hate. Dynasties you really, really want to beat. Right now, as LA Galaxy coach Bruce Arena once memorably said: ‘It’s a crapshoot.’”

In short, the MLS lacks one of the joys of an unbalanced league: the David versus Goliath match. And one reason fans enjoy those encounters is that surprisingly often, given their respective budgets, the Davids win. The economist Jack Hirshleifer called this phenomenon “the paradox of power.” Imagine, he said, that there were two tribes, one large, one small. Each can devote its efforts to just two activities, farming and fighting. Each tribe produces its own food through farming, and steals the other tribe’s food through fighting. Which tribe will devote a larger share of its efforts to fighting?

The answer is the small tribe. The best way to understand this is to imagine that the small tribe is very small indeed. It would then have to devote almost all its limited resources to either fighting or farming. If it chose farming, it would be vulnerable to attack. Everything it produced could be stolen. On the other hand, if the tribe devoted all its resources to fighting, it would have at least a chance of stealing some resources. So Hirshleifer concludes—and proves with a mathematical model—that smaller competitors will tend to devote a greater share of resources to competitive activities.

He found many real-world examples of the paradox of power. He liked citing Vietnam’s defeat of the US, but one might also add the Afghan resistance to the Soviet Union in the 1980s, the Dutch resistance to the Spanish in the sixteenth century, or the American resistance to the British in the Revolutionary War. In these cases the little guy actually defeated the big guy. In many other cases, the little guy was eventually defeated, but at much greater cost than might have been expected based on physical resources (the Spartans at Thermopylae, the Afrikaners in the Boer War, the Texans at the Alamo).

In soccer as in war, the underdog tends to try harder. Big teams fight more big battles, and so each big contest weighs slightly less heavily than it does for their smaller rivals. Little teams understand

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Unstoppable by Maria Sharapova(3114)

The Inner Game of Tennis by W. Timothy Gallwey(2985)

Urban Outlaw by Magnus Walker(2945)

Crazy Is My Superpower by A.J. Mendez Brooks(2856)

The Social Psychology of Inequality by Unknown(2303)

The Fight by Norman Mailer(2152)

Unstoppable: My Life So Far by Maria Sharapova(2126)

Going Long by Editors of Runner's World(1919)

Accepted by Pat Patterson(1913)

Motorcycle Man by Kristen Ashley(1855)

The Sports Gene: Inside the Science of Extraordinary Athletic Performance by David Epstein(1820)

The Happy Runner by David Roche(1818)

Backpacker the Complete Guide to Backpacking by Backpacker Magazine(1811)

Sea Survival Handbook by Keith Colwell(1789)

Futebol by Alex Bellos(1782)

Mind Fuck by Manna Francis(1739)

Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise by Anders Ericsson & Robert Pool(1659)

Endure by Alex Hutchinson(1600)

The Call of Everest by Conrad Anker(1547)