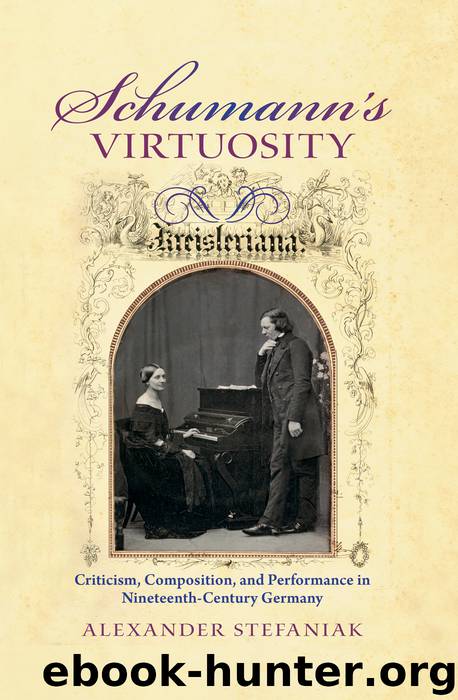

Schumann's Virtuosity by Alexander Stefaniak

Author:Alexander Stefaniak

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Indiana University Press

Published: 2016-01-24T16:00:00+00:00

Part II

Schumann’s Virtuosity and the Culture of the Work Concept

In his review of the 1836–1837 Leipzig Gewandhaus season, Schumann paused from discussing individual performances and imagined the concerts as a panoramic tableau:

As my imagination strove to condense everything into one picture, all of a sudden a sort of blossoming mountain of the muses stood before me, upon which I saw under the eternal temple of the older masters new arcades, new paths, and among them, merry virtuosos and lovely singers like flowers and butterflies: all of this in such a rich fullness and bewildering alternation, that the common and insignificant overlooked themselves on their own.1

As Schumann’s description suggests, the concerts blended venerated composers, canonized masterworks, and recent music that, for him, continued this legacy. The season had immersed audiences in Haydn (two unspecified symphonies), Mozart (including Symphonies Nos. 40 and 41), and Beethoven (including Symphonies Nos. 2, 4, 5, 8, and 9). Not that the concerts fixated exclusively on the past—Schumann described new wings and thoroughfares. For example, the orchestra performed overtures such as Mendelssohn’s Midsummer Night’s Dream and Meeresstille und glückliche Fahrt and William Sterndale Bennett’s Die Najaden. The concerts also exemplified the heterogeneous programming typical of the first half of the century. Some virtuosos entered the temple performing concertos by Bach, Mozart, or Beethoven. Others offered popularly styled showpieces, such as when violinist Karol Lipiński played his variations on Rossini’s Il barbiere di Siviglia, and vocalists performed operatic numbers by Donizetti, Mercadante, and Spontini.2 In Schumann’s description, this musical heterogeneity thrived in the shadow of the “eternal temple” and its new additions. If he seemed to portray virtuosos as decoration rather than superstructure, he nonetheless made it clear that they inhabited and enriched the mountaintop and its edifices.

Schumann painted a scene at once venerable and idyllic. Mount Parnassus, mythical home of Apollo and the nine muses, evokes timeless value and classical equanimity. The affective qualities Schumann described in this essay differed from those we have encountered so far in this book: not the otherworldly, mysterious effects the Davidsbündler heard in Chopin’s “Là ci darem la mano” Variations, the convivial idealism of Voigt’s salon, or the overwhelming power of Liszt’s 1840 concerts, but Apollonian solidity and repose.

The Leipzig tableau captures the most often-cited way in which nineteenth-century virtuosos presented their work as having transcendent qualities: attempting to synthesize virtuosity and the work concept. The work concept is a complex, multifaceted ideal that is central to nineteenth-century musical aesthetics. At its heart was the belief that musical life should revolve first and foremost around the composition, performance, discussion—and, potentially, the veneration—of musical works. The work concept shaped musical life in ways ranging from abstract thinking about the ontology of music, to programming and performance practices, to publication endeavors (critical editions and study scores, for example), to compositions themselves.3 By embracing it, musicians and listeners valorized the composer over the performer, the composition over its ephemeral performances.

No mere intellectual exercise, the work concept elevated music among the arts and within society. One of its most significant manifestations was a long process of canon formation.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Goal (Off-Campus #4) by Elle Kennedy(13640)

Kathy Andrews Collection by Kathy Andrews(11796)

Diary of a Player by Brad Paisley(7539)

Assassin’s Fate by Robin Hobb(6188)

What Does This Button Do? by Bruce Dickinson(6187)

Big Little Lies by Liane Moriarty(5773)

Altered Sensations by David Pantalony(5088)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(4984)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(4174)

The Death of the Heart by Elizabeth Bowen(3596)

The Heroin Diaries by Nikki Sixx(3534)

Beneath These Shadows by Meghan March(3292)

Confessions of a Video Vixen by Karrine Steffans(3291)

How Music Works by David Byrne(3247)

The Help by Kathryn Stockett(3130)

Jam by Jam (epub)(3069)

Harry Potter 4 - Harry Potter and The Goblet of Fire by J.K.Rowling(3048)

Computational Linguistics and Intelligent Text Processing: 20th International Conference, CICLing 2019 La Rochelle, France, April 7â13, 2019 Revised Selected Papers, Part I by Alexander Gelbukh(2975)

Strange Fascination: David Bowie: The Definitive Story by David Buckley(2848)