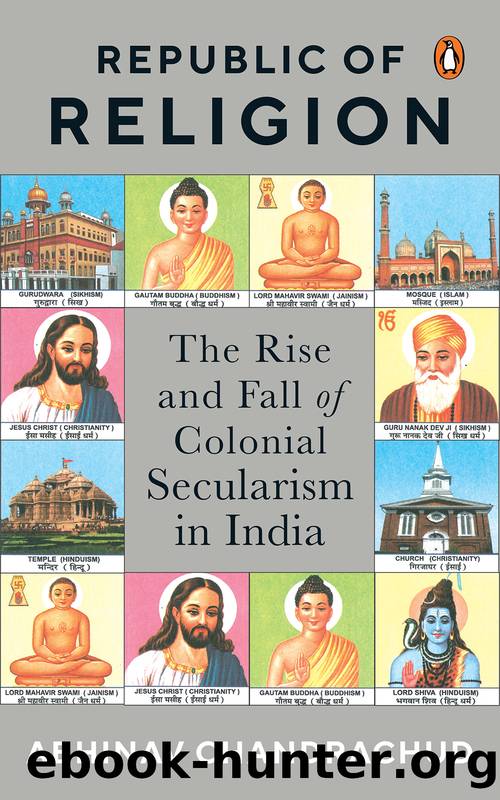

Republic of Religion by Chandrachud Abhinav

Author:Chandrachud, Abhinav [Chandrachud, Abhinav]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Penguin Random House India Private Limited

Published: 2020-01-21T16:00:00+00:00

5

To Divorce Religion from Personal Law

This chapter explores how the notion of ‘personal law’ 1 emerged in British India and why colonial legislators did not enact a uniform civil code in family matters. We will see that the British government adopted a policy of non-interference in religious laws, inspired by the Roman Empire where the customs of conquered people were left intact as far as they were compatible with the conqueror’s norms. However, the colonial government then repeatedly violated its own policy and legislated on religious issues. It faced almost no opposition when it enacted statutes that supplanted Hindu and Muslim laws in the public sphere—laws dealing with subjects like contracts, evidence and crime. However, orthodox Indians repeatedly complained whenever the government tried to interfere with personal laws concerning the family, even if those laws were benevolent and well-conceived, like those abolishing sati or raising the age of consent for sexual intercourse from ten to twelve years. We will therefore see that the absence of a uniform civil code in India has its origins not in the principle of non-interference by the government in religious matters (since religious laws in the public sphere on subjects like contracts and evidence were freely altered during the colonial period), but in the principle of freedom from interference in the home and family.

After 1935, Indian leaders became members of the legislature in large numbers, and the colonial government abandoned its policy of non-interference in personal religious matters which had held sway since the time of Warren Hastings in 1772. Thereafter, the Constitution of independent India also formally renounced colonial secularism by making the enactment of a uniform civil code a directive principle of state policy. The existence of separate personal laws was seen by the framers of the Constitution (and subsequently by the courts of independent India) as one of the factors inhibiting national unity. However, in the decades thereafter, while the courts have attempted to reform Muslim personal law, the Government of India has relapsed into an informal policy of retaining the personal law of Muslims on questions like marriage and inheritance. In other words, the informal policy of the government of independent India towards Muslim personal law has been much the same as the formal policy of Governor General Warren Hastings towards Hindu and Muslim personal law.

In this chapter, we will also see that while enacting statutes dealing with personal law (e.g. those abolishing sati or permitting Hindu widows to remarry), colonial legislators expressly investigated whether the religious practice that was sought to be reformed was essential to the religion in question or not. This set the tone for what the Supreme Court would hold in Shirur Mutt’s case , which we have seen in the previous chapter, and in cases like Shayara Bano , which will be examined herein, as to whether a practice constitutes an integral part of religion.

Personal Law in British India

A Uniform Civil Code in England

During the period of British rule in India, England did not (and continues not to) 2 have a separate set of personal laws, i.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(3516)

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen(3481)

World without end by Ken Follett(3006)

Ants Among Elephants by Sujatha Gidla(2924)

Blood and Sand by Alex Von Tunzelmann(2608)

Japanese Design by Patricia J. Graham(2556)

City of Djinns: a year in Delhi by William Dalrymple(2136)

Inglorious Empire by Shashi Tharoor(2100)

Foreign Devils on the Silk Road: The Search for the Lost Treasures of Central Asia by Peter Hopkirk(2056)

In Order to Live: A North Korean Girl's Journey to Freedom by Yeonmi Park(2052)

Tokyo by Rob Goss(2018)

India's Ancient Past by R.S. Sharma(1987)

India's biggest cover-up by Dhar Anuj(1983)

The Great Game: On Secret Service in High Asia by Peter Hopkirk(1960)

Tokyo Geek's Guide: Manga, Anime, Gaming, Cosplay, Toys, Idols & More - The Ultimate Guide to Japan's Otaku Culture by Simone Gianni(1946)

Goodbye Madame Butterfly(1934)

The Queen of Nothing by Holly Black(1752)

Living Silence in Burma by Christina Fink(1728)

Batik by Rudolf Smend(1720)