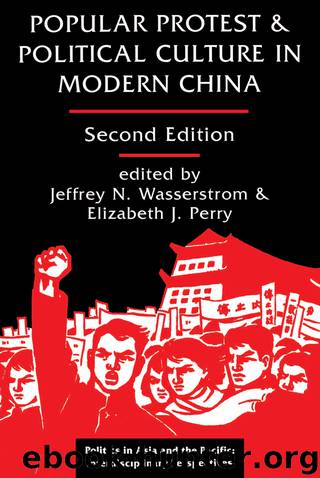

Popular Protest and Political Culture in Modern China by Wasserstrom Jeffrey N.; Perry Elizabeth J.; & Elizabeth J. Perry

Author:Wasserstrom, Jeffrey N.; Perry, Elizabeth J.; & Elizabeth J. Perry

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Routledge

The Problem of Chinese Intellectuals

The literary critic Luo Changpei did not live to see the seventieth anniversary of May Fourth. He did not have a chance to comment on the fate of Chinese intellectuals forty years after the founding of the People's Republic. But his younger colleagues did gather in early May of 1989 to assess their past and their future in light of the "old tune" of May Fourth. The most explicit statement of their concern was inscribed on the banner that hung above the conference at the Sleeping Buddha Temple: "May Fourth and the Problem of Chinese Intellectuals."

Those speaking beneath the banner were all survivors. They were victims of various criticism campaigns directed against China's educated elite from the 1950s onward. Some of the participants of the 1989 conference had been labeled "rightists" in 1957, after Mao found their expression of critical thought intolerable during the short-lived Hundred Flowers Movement. Many more had suffered when intellectuals became labeled members of the "stinking ninth" category during the Cultural Revolution. The "crime" of this group (deemed more odious than landlords, capitalists, Kuomintang sympathizers, etc.) was simply higher education. Having made a living with their minds, intellectuals were excommunicated from the sacred community of peasants and workers.

Thrown out of jobs, publicly humiliated, incarcerated in "cow pens" (as holding cells for intellectuals were known during the Cultural Revolution), these scholars had paid dearly for Mencius's ancient claim that those who labor with their minds are to rule over those who labor with their brawn. Mao had willfully, cruelly reversed the traditional Chinese veneration of the educated. By the time of his death in 1976, intellectuals had lost almost all of their former social status and much of their self-confidence as well. Rehabilitation began slowly and, predictably, from the top: Deng Xiaoping, a survivor himself, declared at the 1978 National Science Conference that the overwhelming majority of the intellectuals were indeed part of the working class. Like those who engage in physical labor, those who engage in mental labor are all socialist workers. Once renamed as workers (gongzuo zhe), intellectuals could hope for a little better housing, a little better pay. But their social calling—especially their right to comment critically about urgent political issues facing China in the age of reform—remained suspect in the eyes of Communist Party rulers.

In April 1986, a new one appeared on new fifty-yuan notes issued by the China People's Bank. It showed an intellectual with gray hair and tie alongside a worker and a peasant. The intellectual had replaced the soldier in the previous trinity. This was a symbolic step forward in the public rehabilitation of intellectuals. It was also a symbolic concession to the Confucian world-view that held the educated elite to be the foundation of Chinese society— along with peasants and, to a lesser extent, artisans. Soldiers, according to tradition, were the lowest, most ill regarded rung of the social hierarchy.

And yet the rehabilitation of Chinese intellectuals did not go far beyond the realm of the symbolic.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen(4385)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(4203)

World without end by Ken Follett(3474)

Ants Among Elephants by Sujatha Gidla(3463)

Blood and Sand by Alex Von Tunzelmann(3195)

Japanese Design by Patricia J. Graham(3167)

The Queen of Nothing by Holly Black(2587)

City of Djinns: a year in Delhi by William Dalrymple(2554)

Foreign Devils on the Silk Road: The Search for the Lost Treasures of Central Asia by Peter Hopkirk(2463)

India's Ancient Past by R.S. Sharma(2451)

Inglorious Empire by Shashi Tharoor(2437)

Tokyo by Rob Goss(2427)

In Order to Live: A North Korean Girl's Journey to Freedom by Yeonmi Park(2386)

Tokyo Geek's Guide: Manga, Anime, Gaming, Cosplay, Toys, Idols & More - The Ultimate Guide to Japan's Otaku Culture by Simone Gianni(2367)

India's biggest cover-up by Dhar Anuj(2350)

The Great Game: On Secret Service in High Asia by Peter Hopkirk(2344)

Goodbye Madame Butterfly(2250)

Batik by Rudolf Smend(2179)

Living Silence in Burma by Christina Fink(2068)