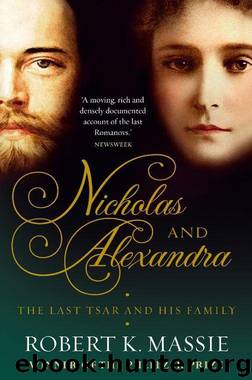

Nicholas and Alexandra: The Tragic, Compelling Story of the Last Tsar and his Family by Massie Robert K

Author:Massie, Robert K. [Massie, Robert K.]

Language: eng

Format: azw3, epub

ISBN: 9781781850565

Publisher: Head of Zeus

Published: 2012-12-31T16:00:00+00:00

Despite the huge losses of the previous autumn, the coming of spring 1915 found the Russian army again ready for battle. Its strength, down to 2,000,000 men in December 1914, had swollen to 4,200,000 as new drafts of recruits arrived at the front. In March, the Russians attacked, hurling themselves again on the Austrians in Galicia. They had immediate, brilliant success. Przemysl, the strongest fortress in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, fell on March 19 with 120,000 prisoners and 900 guns. “Nikolasha [Grand Duke Nicholas] came running into my carriage out of breath and with tears in his eyes and told me,” wrote Nicholas. A Te Deum in the church “was packed with officers and my splendid Cossacks. What beaming faces!” In his joy, the Tsar presented the Grand Duke with an ornamental golden sword of victory, its hilt and scabbard studded with diamonds. Early in April, the Tsar himself entered the conquered province, driving along hot roads covered with white dust. In Przemysl, he admired the fortress—“colossal works, terribly fortified, not an inch of ground remained undefended.” In Lemberg, he spent the night in the house of the Austrian governor-general, occupying a bed hitherto reserved exclusively for the Emperor Franz Joseph.

Once again, waves of Russian infantry and horsemen rolled exultantly up to the Carpathians. The peaks, craggy and thickly forested, were desperately defended by crack Hungarian regiments. Because of their pitiful lack of heavy artillery and ammunition, the Russians were unable to bombard the heights before their attacks. Instead, each hill, each ridge, each crest had to be stormed by bayonet. Advancing with what Ludendorff described as “supreme contempt for death,” the Russian infantry swept upward, leaving the hillsides soaked with blood. By mid-April, the Carpathian passes were in Russian hands and General Brusilov’s Eighth Army was descending onto the Danubian plain. Again Vienna trembled; again there was talk of a separate peace. On April 26, 1915, convinced that the Hapsburg empire was collapsing, Italy declared war on Austria-Hungary.

It was at this moment that Hindenburg and Ludendorff let fall on Russia the monster blow which for months they had been preparing. Having failed to destroy France in 1914, the German General Staff had selected 1915 as the year to drive Russia out of the war. Through March and April, while the Russians devastated the Austrians in Galicia and the Carpathians, the German generals calmly and efficiently massed men and artillery in southern Poland. On May 2, 1,500 German guns opened fire on a single sector of the Russian line. Within a four-hour period, 700,000 shells fell into the Russian trenches.

“From a neighboring height one could see an uninterrupted line of enemy fire for five miles to each side,” wrote Sir Bernard Pares, who witnessed the bombardment. “The Russian artillery was practically silent. The elementary Russian trenches were completely wiped out and so, to all intents and purposes, was human life in that area. The Russian division stationed at this point was reduced from a normal 16,000 to 500.”

In this maelstrom, the Russian line disintegrated.

Download

Nicholas and Alexandra: The Tragic, Compelling Story of the Last Tsar and his Family by Massie Robert K.epub

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Military | Political |

| Presidents & Heads of State | Religious |

| Rich & Famous | Royalty |

| Social Activists |

Waking Up in Heaven: A True Story of Brokenness, Heaven, and Life Again by McVea Crystal & Tresniowski Alex(37013)

Empire of the Sikhs by Patwant Singh(22177)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(18081)

Hans Sturm: A Soldier's Odyssey on the Eastern Front by Gordon Williamson(16733)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(11913)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(10914)

Educated by Tara Westover(7073)

Tools of Titans by Timothy Ferriss(6958)

How to Be a Bawse: A Guide to Conquering Life by Lilly Singh(6698)

The Last Black Unicorn by Tiffany Haddish(5078)

Permanent Record by Edward Snowden(5004)

The Rise and Fall of Senator Joe McCarthy by James Cross Giblin(4851)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(4453)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(4427)

The Crown by Robert Lacey(4111)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4038)

The Iron Duke by The Iron Duke(3643)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(3263)

How to be Champion: My Autobiography by Sarah Millican(3191)