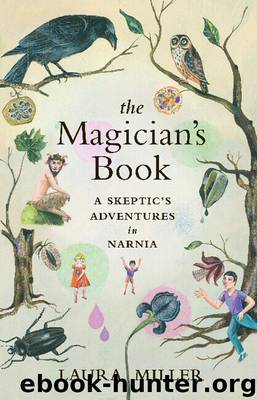

Laura Miller by The Magician's Book: A Skeptic's Adventures in Narnia

Author:The Magician's Book: A Skeptic's Adventures in Narnia

Language: eng

Format: mobi

Tags: BIO000000

ISBN: 0316017639

Publisher: Little, Brown and Company

Published: 2008-12-03T06:00:00+00:00

Chapter Fourteen

Arrows of Desire

According to Bruno Bettelheim, the most important function of fairy tales is unconscious; they echo and give form to the fears, urges, and enigmas already lurking in a child’s mind. Bettelheim thought the stories both expressed and brought coherence to children’s inner lives and were essential aids in the challenge of growing up. When adults worry about exposing children to the monsters and violence in fairy tales, he cautioned, they underestimate the interior tumult with which children are already grappling. “Fairy tale imagery,” wrote Bettelheim, “helps children better than anything else in their most difficult and yet most important and satisfying task: achieving a more mature consciousness to civilize the chaotic pressures of their unconscious.”

Lewis would have agreed with Bettelheim that children can handle the scarier aspects of fairy tales, but that’s about it. Lewis detested Freudianism and satirized it in an early prose allegory entitled The Pilgrim’s Regress. He found Freud’s theories reductive, arguing that if all artistic imagery can be boiled down to nothing more than symbols of infantile sexuality, then “our literary judgments are in ruins.” It was not that he detected no sexual fantasies in art, but rather that there was so much else there as well that sex struck him as the least of it. Besides, Freudian criticism often engages in what Lewis rejected as “the personal heresy,” the study of texts as glosses on the minds of their creators. “The poet,” Lewis wrote, “is not a man who asks me to look at him; he is a man who says ‘look at that’ and points.” This riposte, of course, sidesteps the question of what the poet communicates about himself — intentionally or otherwise — by his style of pointing and by the things he chooses to point at.

Psychoanalysis frequently assumes that a patient who passionately denies a motive or an anxiety is really concealing the presence of that very feeling. (This is the original clinical meaning of “denial.”) As a therapeutic tool, this concept leaves a lot to be desired — as almost anyone would conclude from reading Freud’s case histories. I first read Fragments of an Analysis of a Case of Hysteria, better known as Dora, in an undergraduate course on psychoanalytic criticism. Our young instructor wanted to move quickly past the basic Freudian principles so that he could get to the work of Jacques Lacan, then a relatively new and fashionable theorist. With unconcealed impatience, he let several of us (all women) vent our outrage over Freud’s treatment of his patient, poor Dora, a young Viennese woman whose father was sleeping with the wife of a friend and who, his daughter suspected, was tacitly encouraging the friend to sleep with Dora by way of compensation. Freud validated Dora’s suspicions (her father, not surprisingly, denied trading his daughter for his friend’s wife), but he also betrayed her by insisting that, contrary to her protests, she really was in love her father’s friend. It’s always a good idea to bear in mind that Freud’s theories usually failed at their primary, stated purpose: helping his patients.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Fantasy | Gaming |

| Science Fiction | Writing |

Sita - Warrior of Mithila (Book 2 of the Ram Chandra Series) by Amish(54862)

The Crystal Crypt by Dick Philip K(36856)

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(15334)

Always and Forever, Lara Jean by Jenny Han(14899)

Ready Player One by Cline Ernest(14643)

The Last by Hanna Jameson(10247)

Year One by Nora Roberts(9783)

Persepolis Rising by James S. A. Corey(9349)

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(8975)

Never let me go by Kazuo Ishiguro(8878)

Red Rising by Pierce Brown(8760)

Dark Space: The Second Trilogy (Books 4-6) (Dark Space Trilogies Book 2) by Jasper T. Scott(8170)

The handmaid's tale by Margaret Atwood(7757)

The Circle by Dave Eggers(7104)

Frank Herbert's Dune Saga Collection: Books 1 - 6 by Frank Herbert(7060)

The Testaments by Margaret Atwood(6881)

Legacy by Ellery Kane(6649)

Pandemic (The Extinction Files Book 1) by A.G. Riddle(6530)

Six Wakes by Mur Lafferty(6239)