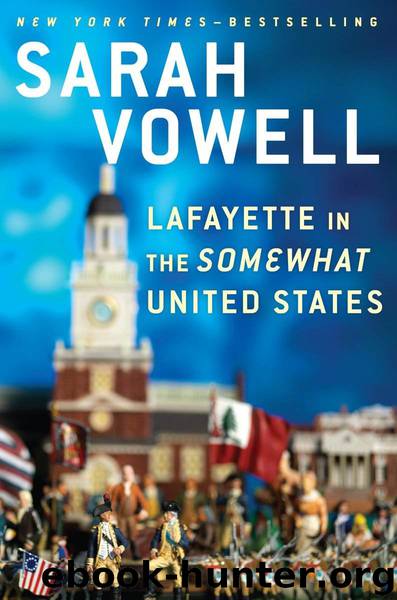

Lafayette in the Somewhat United States by Sarah Vowell

Author:Sarah Vowell [Vowell, Sarah]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: History, Nonfiction, Retail, Revolutionary Period (1775-1800), United States

ISBN: 9781594631740

Google: q-pJBgAAQBAJ

Amazon: 1594631743

Publisher: Penguin

Published: 2015-10-20T04:00:00+00:00

Over a decade after the Treaty of Alliance was signed, in the early days of the French Revolution, a forlorn Louis XVI would answer a letter from his Indian ally Tipu Sultan of Mysore, who was seeking French help in his war with the forces of Britain’s East India Company under the command of our old pal Cornwallis. (This conflict on the subcontinent, by the way, became a footnote in U.S. history when the Mysoreans’ missiles intrigued a British Army engineer, who went on to design his own versions for the redcoats, including those fired by the British fleet at Fort McHenry in 1814 and witnessed by Francis Scott Key, who immortalized “the rockets’ red glare” in our national anthem, thus proving that the hippie saps are right and we really are all connected—by weaponry.) Anyway, Louis replied to the sultan, “This occasion”—being hit up for money, men, and arms to combat his old nemeses the British—“greatly resembles the American affair of which I never think without regret. On that occasion, they took advantage of my youth, and today we are paying the price for it.”

The most influential member of this “they” who talked Louis into the alliance with the Americans was undoubtedly his foreign minister Vergennes. After Franklin’s audience with the king, the treaty celebrations at Versailles culminated in a dinner hosted by Vergennes with Franklin seated next to him in the chair that traditionally had been reserved for the British ambassador. Nearly three years after Vergennes’s spy in Philadelphia gave Franklin vague assurances that France wished the rebels well, Franklin and Vergennes could finally rejoice in person, and more important, in public.

In the months between the signing of the Franco-American Treaty of Alliance on February 6, 1778, and its ratification by the Continental Congress on May 4, Britain declared war on France. At the same time, British prime minister Lord North also spearheaded a last-ditch effort at reconciliation with the colonies. North dispatched a doomed “peace commission” to meet with Congress and delivered an address to the House of Commons on February 17 suggesting that the British government should capitulate on all the Americans’ prewar sticking points, except for recognizing independence. His hope, however faint, was that the colonists would go back to being subjects of the crown if the Coercive Acts were repealed, Parliament gave up the right to tax the colonies, the Continental Congress was recognized as “a legal body,” and Americans were allowed to elect members of the House of Commons. According to a contemporary periodical’s coverage of this speech, the MPs’ reaction to these suggestions was “a dull melancholy silence,” then “astonishment, dejection and fear.”

What a waste. The previous twelve years of bad blood and corpses could have been avoided if these same astonished and dejected men had paid attention to Ben Franklin’s testimony about the Stamp Act before the House of Commons back in 1766. He acknowledged that while at that moment Britain “will not find a rebellion” in her colonies, he warned

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| African Americans | Civil War |

| Colonial Period | Immigrants |

| Revolution & Founding | State & Local |

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(13877)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(12938)

Underground: A Human History of the Worlds Beneath Our Feet by Will Hunt(11263)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(11060)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(10914)

American History Stories, Volume III (Yesterday's Classics) by Pratt Mara L(4828)

Perfect Rhythm by Jae(4627)

Wiseguy by Nicholas Pileggi(4595)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(4348)

Paper Towns by Green John(4173)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4037)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(4013)

The Mayflower and the Pilgrims' New World by Nathaniel Philbrick(3917)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(3736)

Too Much and Not the Mood by Durga Chew-Bose(3697)

Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI by David Grann(3614)

The Borden Murders by Sarah Miller(3592)

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen(3497)

Killing England by Bill O'Reilly(3459)