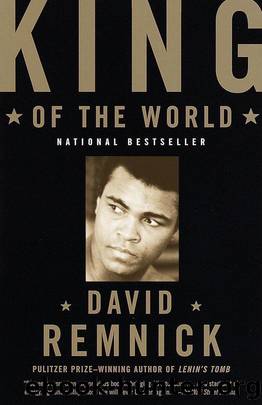

King of the World: Muhammad Ali and the Rise of an American Hero by David Remnick

Author:David Remnick

Language: eng

Format: azw3

Tags: Autobiography, Non-Fiction, Boxing, Sports, Olympics, Biography

ISBN: 9780804173629

Publisher: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group

Published: 2014-04-01T23:00:00+00:00

BILL MACDONALD NEVER HOPED TO CONVINCE THE PUBLIC that Clay was a modest fellow in the Louis mold, but he had hoped that the writers would think he could fight. They did not. According to one poll, 93 percent of the writers accredited to cover the fight predicted Liston would win. What the poll did not register was the firmness of the predictions. Arthur Daley, the New York Times columnist, seemed to object morally to the fight, as if the bout were a terrible crime against children and puppies: âThe loudmouth from Louisville is likely to have a lot of vainglorious boasts jammed down his throat by a hamlike fist belonging to Sonny Liston.â¦â

In the later acts of his career, Muhammad Ali would take his place in the television firmament and his Boswell would be Howard Cosell. But in the days preceding his fight with Sonny Liston in Miami, Cassius Clay was not yet Muhammad Ali and Howard Cosell was a bald, nasal guy on the radio who annoyed his colleagues with his portentous questions and his bulky tape recorder, which he was forever bashing into someoneâs giblets. Newspapers were still the dominant force in sports; columnistsâwhite columnistsâwere the dominant voices; and Jimmy Cannon, late of the New York Post and, since 1959, of the New York Journal-American, was the king of the columnists. Cannon was the first thousand-dollar-a-week man, Hemingwayâs favorite, Joe DiMaggioâs buddy, and Joe Louisâs iconographer. Red Smith, who wrote for the Herald Tribune, employed an elegant restraint in his prose that put him ahead of the game with more high-minded readers, but Cannon was the popular favorite: a world-weary voice of the city. Cannon was king, and Cannon had no sympathy for Cassius Clay. He did not even think he could fight.

One afternoon shortly before the fight, Cannon was sitting with George Plimpton at the Fifth Street Gym watching Clay spar. Clay glided around the ring, a feather in the slipstream, and every so often he popped a jab into his sparring partnerâs face. Plimpton was completely taken with Clayâs movement, his ease, but Cannon could not bear to watch.

âLook at that!â Cannon said. âI mean, thatâs terrible. He canât get away with that. Not possibly.â It was just unthinkable that Clay could beat Liston by running, carrying his hands at his hips, and defending himself simply by leaning away.

âPerhaps his speed will make up for it,â Plimpton put in hopefully.

âHeâs the fifth Beatle,â Cannon said. âExcept thatâs not right. The Beatles have no hokum to them.â

âItâs a good name,â Plimpton said. âThe fifth Beatle.â

âNot accurate,â Cannon said. âHeâs all pretense and gas, that fellow.⦠No honesty.â

Clay offended Cannonâs sense of rightness the way flying machines offended his fatherâs generation. It threw his universe off kilter.

âIn a way, Clay is a freak,â he wrote before the fight. âHe is a bantamweight who weighs more than two hundred pounds.â

Cannonâs objections went beyond the ring. His hero was Joe Louis, and for Joe Louis he composed the immortal line that he was a âcredit to his raceâthe human race.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Boxing | Martial Arts |

| Wrestling |

Imperfect by Sanjay Manjrekar(5422)

Wiseguy by Nicholas Pileggi(4619)

Tuesdays with Morrie by Mitch Albom(3854)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(3846)

Unstoppable by Maria Sharapova(3124)

Crazy Is My Superpower by A.J. Mendez Brooks(2873)

Not a Diet Book by James Smith(2749)

Into Thin Air by Jon Krakauer(2718)

The Mamba Mentality by Kobe Bryant(2680)

Finding Gobi by Dion Leonard(2272)

My Turn by Johan Cruyff(2250)

Tuesdays With Morrie by Mitch Albom(2183)

The Fight by Norman Mailer(2164)

Unstoppable: My Life So Far by Maria Sharapova(2133)

The Ogre by Doug Scott(2127)

Accepted by Pat Patterson(1922)

The Quarterback Whisperer by Bruce Arians(1851)

Everest the Cruel Way by Joe Tasker(1833)

Open Book by Jessica Simpson(1801)