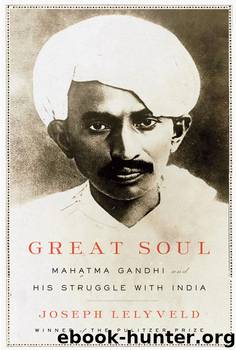

Great Soul by Joseph Lelyveld

Author:Joseph Lelyveld [Lelyveld, Joseph]

Language: eng

Format: epub, mobi

ISBN: 978-0-307-59536-2

Publisher: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group

Published: 2011-03-28T16:00:00+00:00

He may have meant to offer Ambedkar “the gentlest treatment,” may not have been thinking of Ambedkar at all, when he led off with a political barb, noting in the politest possible terms that the British had stacked the conference with political lightweights and nonentities as a way of diminishing, of getting around, the national movement. Gandhi, the recognized national leader, was just one of fifty-six delegates, placed by the imperial stage managers on an equal footing with British businessmen, maharajahs, and representatives of various minorities and sects. So Gandhi had a point, but the untouchable spokesman could have once again discerned condescension and taken offense. Then, heedless of overstatement, Gandhi allowed himself to claim, “Above all, the Congress represents, in its essence, the dumb, semi-starved millions scattered over the length and breadth of the land in its 700,000 villages.” Now we know this wasn’t really his reading of Indian reality. In the setting of St. James’s Palace, Gandhi was plainly glossing over his own disappointment in the Congress’s failure to do more than pay lip service to his “constructive program” for renewal at the village level. Less than two years earlier, he’d told Nehru that the movement couldn’t be trusted to conduct a civil disobedience campaign. But here he was allowing himself rhetorical leeway as the Congress’s spokesman and plenipotentiary, staking his claim on what was still not much more than an aspiration.

To Ambedkar’s sensitive ears, it was propaganda calculated to belittle him and his struggle for the recognition of untouchables as a distinct and persecuted Indian minority, therefore demanding rebuttal. If the Congress represented the poorest, what role could he have, standing outside the national movement as he did? Three days later Gandhi made a potentially soothing gesture, saying, “Of course, the Congress will share the honor with Dr. Ambedkar of representing the interests of the untouchables.” But in the next breath he swept Ambedkar’s ideas for untouchable representation off the table. “Special representation” for them, he said, would run counter to their interests.

The clash between Ambedkar and Gandhi became personal in a session of what was named the Minorities Committee, on October 8, 1931, a day after Prime Minister MacDonald called a snap election that would produce a Tory landslide behind the facade of a national unity government, giving the Tories more than three-quarters of the seats in the new House of Commons. It was Ambedkar who lit the fuse, ignoring the Mahatma’s offer to “share the honor” of representing the untouchables. He may have been nominated by the British, but, nevertheless, Ambedkar said, “I fully represent the claims of my community.” Gandhi had no claim, he now seemed to argue, on the support of untouchables: “The Mahatma has always been saying that the Congress stands for the Depressed Classes, and that the Congress represents the Depressed Classes more than I or my colleagues can do. To that claim I can only say that it is one of the many false claims which irresponsible people keep on making.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| China | India & South Asia |

| Japan |

Fanny Burney by Claire Harman(25810)

Empire of the Sikhs by Patwant Singh(22204)

Out of India by Michael Foss(16327)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(11951)

Small Great Things by Jodi Picoult(6123)

The Six Wives Of Henry VIII (WOMEN IN HISTORY) by Fraser Antonia(4811)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(4437)

The Lonely City by Olivia Laing(4142)

The Crown by Robert Lacey(4126)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4054)

The Iron Duke by The Iron Duke(3664)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(3592)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(3466)

Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors by Piers Paul Read(3333)

Papillon (English) by Henri Charrière(3293)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(3281)

Stalin by Stephen Kotkin(3104)

Aleister Crowley: The Biography by Tobias Churton(3040)

Ants Among Elephants by Sujatha Gidla(2938)