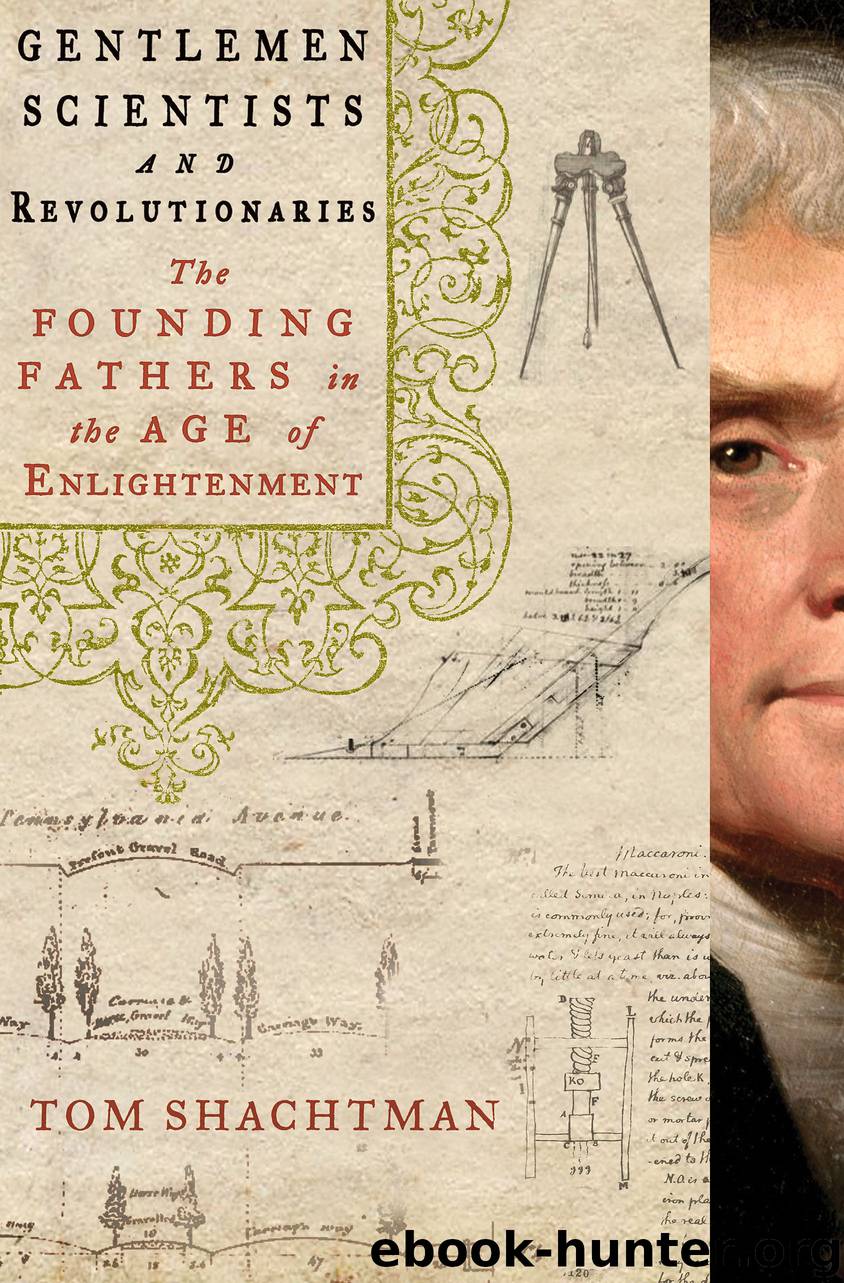

Gentlemen Scientists and Revolutionaries by Tom Shachtman

Author:Tom Shachtman

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: St. Martin's Press

Published: 2014-08-11T16:00:00+00:00

Ten

Midcourse Corrections

The war was only the “first act” of an American Revolution, Benjamin Rush reminded his countrymen: “It remains yet to establish and perfect our new forms of government, and to prepare the principles, morals, and manners of our citizens for these forms.” While the Founders had not formally articulated a hypothesis underlying the governance of the new United States of America, one was nevertheless generally understood: that a confederation of former colonies whose interests overlapped at times, but only at times, could be governed in a democratic way, without a monarch or a powerful parliament, and could remain stable in the face of exterior or interior attacks. George Washington’s 1783 “Circular to the States,” sent after receiving the news of the peace treaty’s signing, expressed well the circumstances under which the hypothesis had been formed:

When we consider the magnitude of the prize we contended for, the doubtful nature of the contest, and the favorable manner in which it has terminated, we shall find the greatest possible reason for gratitude and rejoicing. . . . The foundation of our Empire was not laid in the gloomy age of Ignorance and Superstition, but at an Epocha when the rights of mankind were better understood and more clearly defined, than at any former period, the researches of the human mind, after social happiness, have been carried to a great extent, the Treasures of knowledge, acquired by the labours of Philosophers, Sages and Legislatures . . . are laid open for our use, and their collected wisdom may be happily applied in the Establishment of our forms of Government .1

Scientific hypotheses, to be considered valid, must explain all the extant facts. The Founders’ governing configuration did so by showing that all prior, authoritarian forms of governance had proved inadequate to governing a free people, and by configuring a democracy that was designed to ameliorate the wrongs of those authoritarian forms; but a good hypothesis must also be able to encompass facts not yet in evidence. For the Founders, that second requirement was quite palpable after the war, as was its corollary demand, that if the current governmental configuration proved unable to meet new challenges resulting from independence, the hypothesis merited adjustment, to be accomplished in ways that did not compromise that government’s democratic integrity and power.

In Jürgen Habermas’s terms, at the close of the Revolutionary War, Americans existed within new “frames of reference”: they were now fellow citizens rather than fellow subjects, sovereign actors in a society in which distinctions of inherited class no longer officially obtained, and they were being served by elected leaders rather than dictated to by royal appointees. The new configurations were part of a predictable upheaval attendant on what Gordon Wood characterizes as a radical reordering of the whole of American society. As St. John de Crèvecoeur wrote in 1782, “What is an American? The American is a new man, who acts on new principles; he must therefore entertain new ideas, and form new opinions.”2 Many

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| African Americans | Civil War |

| Colonial Period | Immigrants |

| Revolution & Founding | State & Local |

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(15331)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14481)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12369)

Underground: A Human History of the Worlds Beneath Our Feet by Will Hunt(12085)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12014)

Wiseguy by Nicholas Pileggi(5767)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5429)

Perfect Rhythm by Jae(5396)

American History Stories, Volume III (Yesterday's Classics) by Pratt Mara L(5297)

Paper Towns by Green John(5175)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(4996)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4948)

The Mayflower and the Pilgrims' New World by Nathaniel Philbrick(4487)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4484)

Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI by David Grann(4435)

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen(4384)

Too Much and Not the Mood by Durga Chew-Bose(4337)

The Borden Murders by Sarah Miller(4310)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(4188)