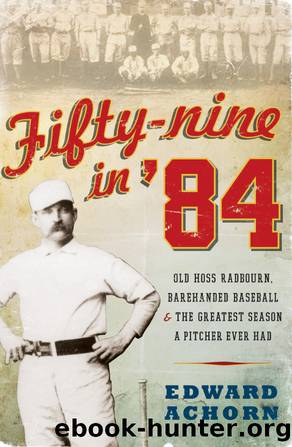

Fifty-Nine in '84 by Edward Achorn

Author:Edward Achorn

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: HarperCollins

Chapter 13

Crackup

Radbourn had failed to pry one dollar out of the Grays for the work they now required of him, handling Sweeneyâs starts as well as his own. That was a snub he found hard to forgive, but he had persuaded management to make one concession. At Radbournâs urgent request, the club had provided him a stoveâprobably from team president Henry T. Rootâs kitchen appliance storeâfor the Graysâ dressing room. It was a new model that employed coal oil, a highly flammable liquid much like kerosene. Such stoves heated up rapidly and threw off a lot of warmth. They were, admittedly, known to explode on rare occasions, even burning their users to death, but that was a risk nineteenth-century Americans seemed willing to take in exchange for the convenience. Even on the most sweltering summer afternoons, Radbourn could now get a hot stove going quickly after games to boil water and steam his aching arm, on the theory that heat would loosen and soothe his muscles.

Modern sports medicine suggests that was exactly the wrong approachâthat Radbourn would have been better off icing down his arm and shoulder, shrinking the inflammation in his muscles. But who knew? The treatment available for lame arms and painful joints was primitive at bestâno arthroscopic surgery, no whirlpool baths, no sophisticated physical therapy. For a sore arm, the Sporting Life recommended a âcrude petroleum remedy,â or this: âRub with a mixture of a dimeâs worth each of sweet oil, liquid ammonia and rye whiskey.â When Bostonâs Ezra Sutton was suffering a sore arm a few years later, the third baseman dropped nickels several times a day into the âelectric machineâ at Baltimoreâs Eutaw House, clutching the handles and receiving a sharp shockâa newfangled therapy believed to cure all sorts of ailments. Sutton concluded that the painful jolts had âdone him lots of good, and that his arm feels better.â But none of these treatments was likely to make a pitcher feel much better toiling day after day.

The art of treating sore arms was becoming an urgent matter in 1884, and Radbourn and Sweeney were not the only duo who required attention. The National Leagueâs expanded regular-season scheduleâwith fourteen additional games, almost one more per weekâwas proving to be more punishing than many of its hard-throwing, two-man rotations could bear. âOne thing is evident. The National league is playing too many games per week; the batteries cannot stand it,â the Fall River Daily Evening News warned. By midseason, it had become an open question whether the extra games were even worth it, given sagging attendance and the increased risk of injury to pitchers and catchers. âBase ball can be run into the ground; the people are called upon to attend too many games and they may, after a year or two more, count the draw on the pocketbook and stay home,â the News argued. âAlready businessmen in Providence say too much time is absorbed. Four games per week is enough. Will managers be wise in time?â

Overexposure was only one reason for dwindling attendance, though.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Baseball | Basketball |

| Boxing, Wrestling & MMA | Football |

| Golf | Hockey |

| Soccer |

Imperfect by Sanjay Manjrekar(5863)

Wiseguy by Nicholas Pileggi(5757)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(5067)

Tuesdays with Morrie by Mitch Albom(4762)

Unstoppable by Maria Sharapova(3518)

Not a Diet Book by James Smith(3403)

Crazy Is My Superpower by A.J. Mendez Brooks(3384)

Into Thin Air by Jon Krakauer(3375)

The Mamba Mentality by Kobe Bryant(3256)

The Fight by Norman Mailer(2921)

Finding Gobi by Dion Leonard(2830)

Tuesdays With Morrie by Mitch Albom(2743)

The Ogre by Doug Scott(2674)

My Turn by Johan Cruyff(2616)

Unstoppable: My Life So Far by Maria Sharapova(2492)

Accepted by Pat Patterson(2361)

Everest the Cruel Way by Joe Tasker(2327)

Borders by unknow(2300)

Open Book by Jessica Simpson(2257)