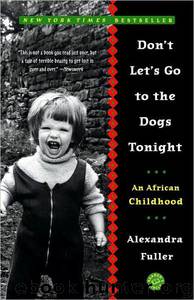

Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight: An African Childhood by Alexandra Fuller

Author:Alexandra Fuller

Language: eng

Format: mobi, epub

Tags: Non-fiction, Travel, Nonfiction, Biography, History

ISBN: 9781588360496

Publisher: Random House

Published: 2001-12-14T10:00:00+00:00

The Fullers—Devuli

DEVULI

On a recent map entitled “Comfort-Discomfort Belts,” Devuli Ranch is shown in the area of Zimbabwe that is shaded with tight red lines. This means that it is an uncomfortably hot place, bordering on oppressive. “Health and efficiency suffer,” the map’s legend says.

The older maps, drawn up in the 1920s, are more blunt. On these old maps, the area in which Devuli Ranch sits has stamped across it in bold black letters, “Not Fit for White Man’s Habitation.”

Dad bends over a map and shows me: “See?” He lights a cigarette and points with the two fingers which hold the cigarette at the ranch. Blue smoke floats over the flat, yellow, red-lined patch of map.

There are no towns anywhere near the ranch, and only one thin road leads past it, described on the map as a strip road. I point this out to Dad.

He says, “Great, isn’t it?” He takes a deep pull on his cigarette and shows me. “Look at the rivers.” There are three rivers running through the ranch.

“Well, that looks watery,” I say, more hopefully.

Dad snorts. “It just looks that way. Dry as a bloody bone.”

“Will we grow tobacco?”

“Cattle,” says Dad. “I’m going to find their cattle.” His thumb covers hundreds of miles and he moves it slowly across the bottom of the map. “All this, see? That’s where the cattle are. They think.”

The herd went wild during the war. They’ve started to range and roam like wild herds of eland or kudu. Dad is going to find, herd, dip, vaccinate, dehorn, castrate, cull, and brand a few thousand head of wild Brahman cattle.

“Will we be the only white people?”

“Almost. There’s the ranch manager and his wife.”

“Are there any kids?”

“Not white kids.”

“Oh.”

“You can help me round up the cattle.”

“Okay.” I am not enthusiastic.

“There are wild horses, too.”

“Oh. Can we train them?”

“Perhaps.”

“How long will we live there?”

Dad smokes and squints up his blue eyes. He says, “I’ve told them if they give me a year, I’ll give them their herd back.”

“And then?”

“We’ll cross that river when we get to it.”

The Turgwe, Save, and Devure rivers flood once or twice each year, each flood within a few weeks of the last. A great wall of water gushing brownly through the scrubby low mopane woodland makes a roaring sound like a thousand Cape buffalo galloping over hollow ground. Floating carcasses of large animals are caught, legs poking up among washed-away trees. Smaller animals, still alive, cling wide-eyed to the branches of the barreling trees, bodies hunched, wet faces pinched with fear. By morning, the flood is over. The rivers lie almost still, swollen, sluggish. And then the rivers dry into smaller and smaller pools, stinking and lurking with scorpions, until nothing is left of them but glittering white sand.

The Africans and animals who have learned to live down here near the ranch, in the lowveldt, dig deep wells into the dry riverbeds until they reach the black, dank water that lies there. For nine months out of every year, these warm, barely ample wells feed everything that is alive within a fifty-mile radius.

Download

Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight: An African Childhood by Alexandra Fuller.epub

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Asia |

| Canadian | Europe |

| Holocaust | Latin America |

| Middle East | United States |

Fanny Burney by Claire Harman(25790)

Empire of the Sikhs by Patwant Singh(22176)

Out of India by Michael Foss(16313)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(11913)

Small Great Things by Jodi Picoult(6105)

The Six Wives Of Henry VIII (WOMEN IN HISTORY) by Fraser Antonia(4797)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(4427)

The Lonely City by Olivia Laing(4122)

The Crown by Robert Lacey(4111)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4038)

The Iron Duke by The Iron Duke(3642)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(3574)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(3456)

Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors by Piers Paul Read(3317)

Papillon (English) by Henri Charrière(3276)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(3263)

Stalin by Stephen Kotkin(3089)

Aleister Crowley: The Biography by Tobias Churton(3024)

Ants Among Elephants by Sujatha Gidla(2927)