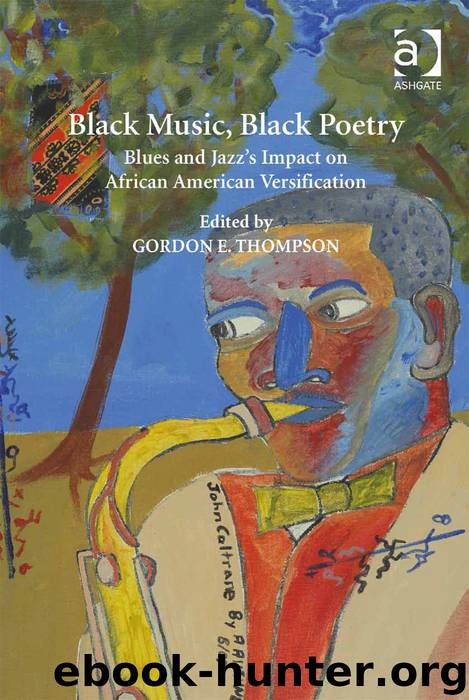

Black Music, Black Poetry: Blues and Jazz's Impact on African American Versification by Thompson Gordon

Author:Thompson, Gordon

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Ashgate Publishing Ltd.

Published: 2014-02-23T16:00:00+00:00

PART III

Lyricism and the Sonic Aesthetic

Chapter 7

Amiri Baraka: Phenomenologist of Jazz Spirit

Christopher Winks

The precept that Amiri Baraka articulated for the New Black Music of the mid-1960s—“Find the self, then kill it” (Jones 1967a: 176)—is also the key to his own aesthetics, founded as it is on his self-reshaping according to the improvisatory demands of being-through-becoming. In his poetry, Baraka demonstrates jazz and the vernacular’s compatibility with Charles Olson’s poetics of projective verse, particularly the “composition by field” and its lessons in kinetics (“the poem itself must, at all points, be a high-energy construct and, at all points, an energy-discharge”), process (“keep it moving as fast as you can, citizen”), and breath (which “allows all the speech force of language back in”) (Olson 1973: 148–9, 152). Anything fixed is dead or moribund; whatever purposively goes toward something and away from something else potentially becomes a live cross-rhythmic reflection of the “changing same” (a concept that in recent years Baraka has modified and extended into the “changing forever”).

Baraka’s poetic voice sounds most eloquently when it is probing its limits, seeking to duplicate the unrelenting self-challenge and soul-search of the best improvisers, to stoke the flames at the simmering core of African American existence in order to forge a mobile continuum of identities, aesthetics, and sounds. His is a project of literary marronage, a guerrilla expropriation of the weapons of meaning and mastery from their owner/expropriators. Undertaken as it is in perilous terrain, such a campaign is fraught with blind alleys, illusory solutions, and betrayals—and Baraka himself has enumerated most of them in his Autobiography.

In the end, what has maintained the integrity of his work throughout his political and ideological transits and transitions has been his deep attunement to music: “Music is my life—it opens me into the deeper sensitivity of the world, what it is really about, past our worlds” (Baraka 1984: 314). If jazz demands that the musician “express his own unique ideas and his own unique voice … achieve, in short, his self-determined identity” (Ellison 1968: 206), Baraka sees this challenge as constitutive of the entire dynamic field of African American creativity and thus as much collective as individual: “The collection of wills is a simple unity like on the street. A bigger music, and muscle, for the move necessary. The swell of a music, of action and reaction, a seeing, thrown in swift slick tone along the entire muscle of a people” (Jones 1967a: 211). The music of the “blues people,” as adumbration of a movement toward cultural and social self-determination, requires poetry to do it justice not by imitating but by being music. By submerging in the deep well of the vernacular the techniques he picked up from Olson, Baraka delineates the contours of a “vicious modernism” that expresses the concrete universal of African American existence: “our own specific look into / the shapely blood of the heart” (Baraka 1991: 213) and whose central challenge or calling-out is articulated in the title of one of Baraka’s early statements

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Goal (Off-Campus #4) by Elle Kennedy(13657)

Kathy Andrews Collection by Kathy Andrews(11812)

Diary of a Player by Brad Paisley(7564)

Assassin’s Fate by Robin Hobb(6200)

What Does This Button Do? by Bruce Dickinson(6195)

Big Little Lies by Liane Moriarty(5790)

Altered Sensations by David Pantalony(5094)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(4996)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(4188)

The Death of the Heart by Elizabeth Bowen(3610)

The Heroin Diaries by Nikki Sixx(3543)

Confessions of a Video Vixen by Karrine Steffans(3301)

Beneath These Shadows by Meghan March(3300)

How Music Works by David Byrne(3261)

The Help by Kathryn Stockett(3139)

Jam by Jam (epub)(3077)

Harry Potter 4 - Harry Potter and The Goblet of Fire by J.K.Rowling(3061)

Computational Linguistics and Intelligent Text Processing: 20th International Conference, CICLing 2019 La Rochelle, France, April 7â13, 2019 Revised Selected Papers, Part I by Alexander Gelbukh(2990)

Strange Fascination: David Bowie: The Definitive Story by David Buckley(2863)