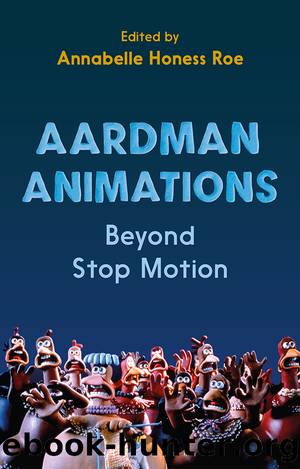

Aardman Animations by Annabelle Honess Roe;

Author:Annabelle Honess Roe;

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Bloomsbury UK

8

Wallace and Gromit and the British Fantasy Tradition

Alexander Sergeant

Aardman Animations is arguably the UK’s finest contemporary exponent of the animated fantasy film. Drawing on what J.P. Telotte describes as animation’s ‘invariably fantastic aspect’,1 Aardman have produced popular animations that display tendencies towards anthropomorphism and comic exaggeration, both of which are also prominent features of traditional fantasy storytelling. This is especially true of the studio’s signature commercial property Wallace and Gromit. Created by Nick Park as part of his final-year project at the National Film and Television School, Wallace and Gromit were first made famous through a series of Oscar-winning shorts aired sporadically on British television between 1989 and 2008. The international popularity of these shorts has spawned a global franchise that has been described as ‘one of the few genuinely eccentric places left in the movies’ and ‘as quintessentially British in flavour as a wedge of Wensleydale’.2 The world of Wallace and Gromit has become synonymous with Aardman itself, existing across an array of media platforms including video games, television spin-offs and other merchandising outlets, but this global popularity has not come at the expense of its British identity. It is, rather, precisely the franchise’s ability to simultaneously celebrate and lampoon concepts of British nationality that gives the distinctly British feel to its characters, scenarios and comedy.

Wallace and Gromit is a fantasy franchise. It features outlandish narratives involving situations that are self-consciously designed to be larger-than-life, not to mention a whole host of non-human characters (dogs, robots, penguins/chickens) who display the fantasy genre’s tendencies towards anthropomorphic caricature. Yet, asserting the identity of Wallace and Gromit as fantasy cinema matters not only because it effects how we might categorize the Aardman franchise in accordance with popular film genre labels, but also how this quintessentially British franchise contributes to discourses of nationality. Despite its similarities to certain aspects of British society, the world of Wallace and Gromit is as much a fantasy as the more obvious secondary fantasy worlds of C.S. Lewis or J.R.R. Tolkien. The only difference is that whilst the worlds of Middle Earth and Narnia display similarities with British culture as part of their respective authors’ attempts to bring authenticity and richness to worlds that are self-consciously unreal, the world of Wallace and Gromit displays elements of self-conscious fantasy within a setting that is ostensibly representative of a certain vision of Northern English society. Contextualizing Wallace and Gromit within what Colin Manlove’ describes as the ‘domestic emphasis’ of British fantasy,3 I wish to explore the narrative and stylistic conventions of the Wallace and Gromit films that establish this distinctly British feel to its fantasy storytelling.

Trading on a set of shared literary and visual influences found within the rich heritage of nineteenth- and twentieth-century British fantasy fiction, Wallace and Gromit becomes quintessentially British not so much in the way it represents reality, but through the way it departs from reality. Viewing Wallace and Gromit through the lens of British fantasy theory, then, reveals an ambivalence in Wallace and Gromit’s attitude towards British identity and British fantasy heritage.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Shoot Sexy by Ryan Armbrust(17142)

Portrait Mastery in Black & White: Learn the Signature Style of a Legendary Photographer by Tim Kelly(16484)

Adobe Camera Raw For Digital Photographers Only by Rob Sheppard(16387)

Photographically Speaking: A Deeper Look at Creating Stronger Images (Eva Spring's Library) by David duChemin(16161)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(13108)

Art Nude Photography Explained: How to Photograph and Understand Great Art Nude Images by Simon Walden(12348)

Perfect Rhythm by Jae(4621)

Pillow Thoughts by Courtney Peppernell(3397)

The Book of Joy by Dalai Lama(3217)

Good by S. Walden(2915)

The Pixar Touch by David A. Price(2739)

Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald by J. K. Rowling(2543)

A Dictionary of Sociology by Unknown(2518)

Humans of New York by Brandon Stanton(2379)

Read This If You Want to Take Great Photographs by Carroll Henry(2303)

Stacked Decks by The Rotenberg Collection(2270)

On Photography by Susan Sontag(2130)

Photographic Guide to the Birds of Indonesia by Strange Morten;(2088)

Insomniac City by Bill Hayes(2083)