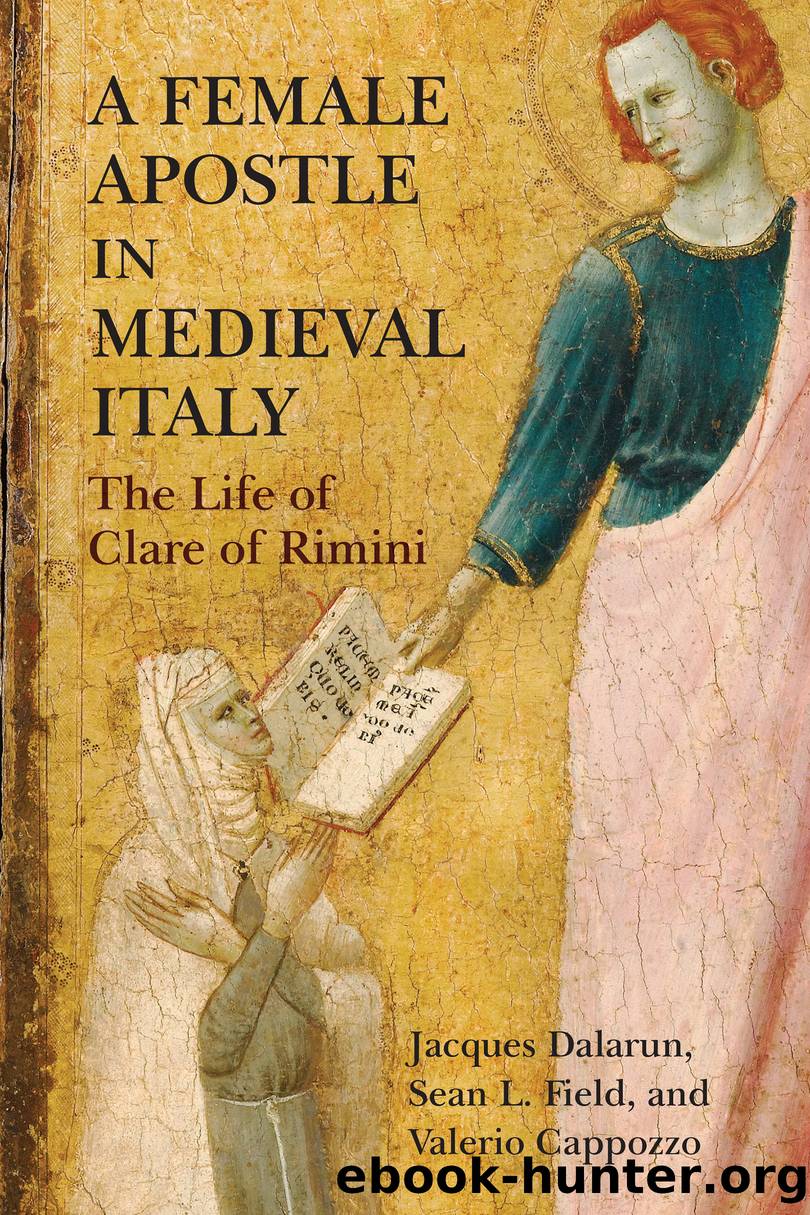

A Female Apostle in Medieval Italy by Jacques Dalarun;Sean L. Field;Valerio Cappozzo;

Author:Jacques Dalarun;Sean L. Field;Valerio Cappozzo;

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Lightning Source Inc. (Tier 2)

* * *

Our hagiographer has already dedicated Chapter 7 to Clareâs success in converting others. Now, after detailing the foundation of her community (Chapters 8 and 9), in Chapter 10 he further develops his picture of Clare as a modern apostle but with a new degree of mobility. Indeed, he revisits several of the same stories first evoked in Chapter 7, spinning them out in greater detail. It may be that our author was not quite sure when these events had happened; he may also have wanted to stress the continuity of this theme throughout Clareâs career. In any case, these episodes tend to replicate a now-familiar story line: initial obstacles are overcome at the price of new accusations, which are finally resolved through proof of divine approval.

âA certain poor little woman came to Sister Clare.â It sounds like the beginning of a fairy tale. The phrase poverella donna (âpoor little womanâ), however, returns us to the vocabulary around Franciscan poverty. St. Francis was often called the Poverello, and he himself referred to Clare of Assisi and her sisters at San Damiano as poverelle. This impoverished womanâs problem was that her daughter did not have the funds necessary to enter the religione of the Santuccia sisters, a community that had been founded by 1270, just outside the walls of Rimini, near the gate of SantâAndrea (see Map 2, in Chapter 5). It housed sisters who followed the way of life established by Santuccia Carabotti of Gubbio (c. 1240â1305). The Santuccia sisters followed a modified version of the Benedictine Rule but devoted themselves to works of charity, gathering alms to help others. Their origins were thus not dissimilar to those of Clareâs emerging foundation. But by the time of their founderâs death, in March 1305, the Santuccia sisters were adhering to a strict social hierarchy typical of many established female orders. In most Benedictine convents, the choir nuns came from aristocratic backgrounds, while âlay sistersâ were of humbler extraction. The Order of St. Clare drew many of its nuns from the urban patrician (like Clare of Riminiâs family) or merchant class, but also accepted serving sisters (still real members of the community) from a lower social stratum. Other women might become tertiaries or, in northern Europe, beguines. Clare of Riminiâs own community is one of the best-documented examples of an experiment in blurring these social distinctions.

The issue was the dowry. Starting in the twelfth century, it became increasingly common for a nobleman to give property or rents to his new son-in-law at the time of his daughterâs marriage. The practice extended to young women who became nuns, or âbrides of Christ.â In other words, a substantial entrance fee was usually necessary for a woman to enter a traditional nunnery. Of course, some women whose families could easily afford such a fee nevertheless preferred a path of evangelical poverty. Douceline of Digne (d. 1274), for instance, could have become a nun of the Order of St. Clare at Genoa but chose to

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32546)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31944)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31929)

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(19052)

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari(14368)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13316)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12018)

Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari(5366)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(5215)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(5092)

Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow by Yuval Noah Harari(4908)

Endurance: Shackleton's Incredible Voyage by Alfred Lansing(4769)

Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl(4583)

The Silk Roads by Peter Frankopan(4526)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(4465)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(4203)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(4101)

The Motorcycle Diaries by Ernesto Che Guevara(4089)

Stalin by Stephen Kotkin(3957)