West Over the Waves by Jayne Baldwin

Author:Jayne Baldwin

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: aviation, history, women's history, flight, nineteen twenties, silent film, aeroplanes, pilot, Atlantic, lost.

Publisher: 2QT Limited (Publishing)

Published: 2017-02-15T00:00:00+00:00

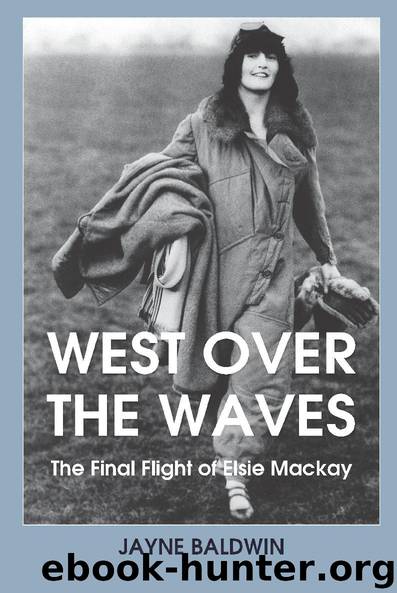

Elsie and Captain Hinchliffe with the Endeavour.

(photograph courtesy of Random House)

Captain Hinchliffe took precautions against the possibility of ice forming on the outer fabric of the plane by coating the fuselage and wings with paraffin. The Endeavour, like many aeroplanes of the period, was covered in fabric stretched tightly across the frame to form a skin and covered with a medium called ‘dope’ – a plasticised lacquer used to tighten, stiffen and waterproof the fabric. Emilie Hinchliffe later wrote that: ‘In short every possible emergency was foreseen and as far as humanly ascertainable, guarded against.’

With these actions completed, all that was left were the full load and endurance tests but another problem arose that had faced those who had previously tackled long-distance flights: the issue of finding a runway long enough to allow a fully loaded plane to take off.

Aviation historian Quentin Wilson, who has studied the Hinchliffe and Mackay flight for many years, explained that, using the details published in the autumn 1928 edition of the RAF Cadet College Magazine, he calculated that the Endeavour would have had an approximate take-off weight of 5809lbs, well above the manufacturer’s maximum of 3800lbs. He concluded that this ‘would have reduced the ability of the aircraft to accelerate resulting in a much longer than normal take-off run.’

Although there were a number of airfields in the UK at that time Captain Hinchliffe decided, as a result of his own calculations, that only one had the sufficient length of runway for such a plane to take off fully loaded. Gaining permission to use that airfield was another matter.

The RAF aerodrome and college at Cranwell near Grantham in Lincolnshire had the necessary length of runway and Hinch had been stationed there as an instructor during the war. However, during his association with Charles Levine the American’s staff had caused considerable trouble; as a result, RAF command had taken the decision that civilians would never be allowed to use the base again. The Honourable Elsie Mackay drew on her top-level connections and her powers of persuasion to gain a meeting with the Secretary of State for Air, Sir Samuel Hoare. Her meeting was successful – to a point. They were given permission to use the base but only for a limited period: one week. It gave them a small window to work with and increased their optimism that the stars were on their side.

The modified Stinson Detroiter had now been customised in distinctive black paint picked out with gold on the struts and wires; this design was part of Elsie’s input to the preparations. It had a large letter G on the side to signify Great Britain and sported two Union Jacks on the fuselage, together with the name Endeavour. The aircraft, serial number 223, also showed an incorrect registration number X41831, its real number being X4183.

On February 24th the plane was flown to Cranwell from Brooklands with Captain Hinchliffe in his usual right-hand seat and Elsie Mackay next to him in the cockpit. Their arrival

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Asia |

| Canadian | Europe |

| Holocaust | Latin America |

| Middle East | United States |

Fanny Burney by Claire Harman(26592)

Empire of the Sikhs by Patwant Singh(23069)

Out of India by Michael Foss(16846)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13315)

Small Great Things by Jodi Picoult(7115)

The Six Wives Of Henry VIII (WOMEN IN HISTORY) by Fraser Antonia(5496)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(5085)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4947)

The Crown by Robert Lacey(4805)

The Lonely City by Olivia Laing(4796)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(4462)

The Iron Duke by The Iron Duke(4349)

Papillon (English) by Henri Charrière(4257)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(4188)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(4098)

Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors by Piers Paul Read(4017)

Stalin by Stephen Kotkin(3956)

Aleister Crowley: The Biography by Tobias Churton(3628)

Ants Among Elephants by Sujatha Gidla(3459)