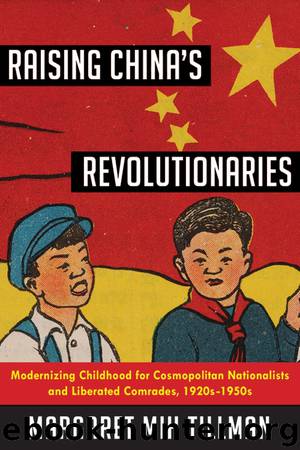

Raising China's Revolutionaries by Margaret Mih Tillman

Author:Margaret Mih Tillman

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Perseus Books, LLC

CHAPTER VII

Women’s Mobilization and Childcare for the Masses

Collective Childcare in the 1950s

Despite the new policies of the People’s Republic of China, a myopic focus on change would, as Paul Cohen argues, obscure important continuities, or enduring problems, across the “1949 divide.”1 Gail Hershatter further demonstrates that a gendered lens provides an important framework for analyzing periodization, one that more adequately considers personal experiences in “domestic time” as distinct from political directives in “campaign time.”2 As advocates, teachers, nurses, and social workers, women had, across the twentieth century, profoundly shaped the implementation of modern childhood, but especially as the social status of male child experts declined, the state relied increasingly on women, especially through the Women’s Federation, to contend with perennial obstacles, such as parental resistance.

One reason for these continuities is that the history of the Chinese Communist Party began nearly three decades before 1949. Inspired by scholarship uncovering the party’s early intellectual diversity, this book points to the widespread flow of ideas regarding modern childhood across the political spectrum, from New Culture paradigms to Chen Heqin’s primers. Child welfare truly attracted broad appeal, despite disagreements over its construction and implementation. Although critical of mission charity in the 1920s, the Chinese Communist Party accepted humanitarian funding, mediated through Allied channels, during World War II. Cadres did not adopt wholesale GMD or U.S. notions of a sentimental childhood, but they emphasized initiatives, such as medical health in childcare institutions, that resonated with U.S. funders’ standards for modern childcare. Communists independently promoted their own aesthetic of a happy, modern childhood. Like the Soviets, they envisioned preschool as the first step away from private family life and toward social collectivization. Political education was conveyed not only through curricular content but through classroom relationships. And yet preschools and kindergartens charged tuition and were not guaranteed by the state. Given these economic barriers, how could the children of peasants and factory workers diversify the “big family” of the kindergarten?

The CCP’s political goals added urgency across 1949 to the enduring issue of distribution. One legacy of American funding was a focus on investing in “demonstration centers” with high-quality care. During the Civil War, prestigious childcare institutions evacuated from Yan’an, and they eventually relocated to major urban areas after 1949. This institutional continuity illustrates the Chinese state’s ongoing difficulty with reconciling early childhood education for the elite and for the disadvantaged. Under the ROC, the National Child Welfare Association had attempted to redress basic social inequalities through humanitarian aid by projecting middle-class values through welfare institutions. In contrast, the PRC sought to overturn inherited notions of class privilege through political education. Nevertheless, the PRC retained the ROC strategy of subsidizing elite “key schools” and maintained government entitlements.3 Cadre schools posed a problem regarding how youth would learn to interact with the masses.

Financial constraints hindered not only an ideological commitment to educate the masses but also an economic mandate to alleviate women’s burdens. Childcare remained primarily (female) gendered work outside of the home, as well as within it. As

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen(4384)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(4202)

World without end by Ken Follett(3474)

Ants Among Elephants by Sujatha Gidla(3460)

Blood and Sand by Alex Von Tunzelmann(3194)

Japanese Design by Patricia J. Graham(3163)

The Queen of Nothing by Holly Black(2586)

City of Djinns: a year in Delhi by William Dalrymple(2547)

Foreign Devils on the Silk Road: The Search for the Lost Treasures of Central Asia by Peter Hopkirk(2454)

India's Ancient Past by R.S. Sharma(2450)

Inglorious Empire by Shashi Tharoor(2436)

Tokyo by Rob Goss(2427)

In Order to Live: A North Korean Girl's Journey to Freedom by Yeonmi Park(2377)

Tokyo Geek's Guide: Manga, Anime, Gaming, Cosplay, Toys, Idols & More - The Ultimate Guide to Japan's Otaku Culture by Simone Gianni(2360)

India's biggest cover-up by Dhar Anuj(2349)

The Great Game: On Secret Service in High Asia by Peter Hopkirk(2329)

Goodbye Madame Butterfly(2249)

Batik by Rudolf Smend(2179)

Living Silence in Burma by Christina Fink(2060)