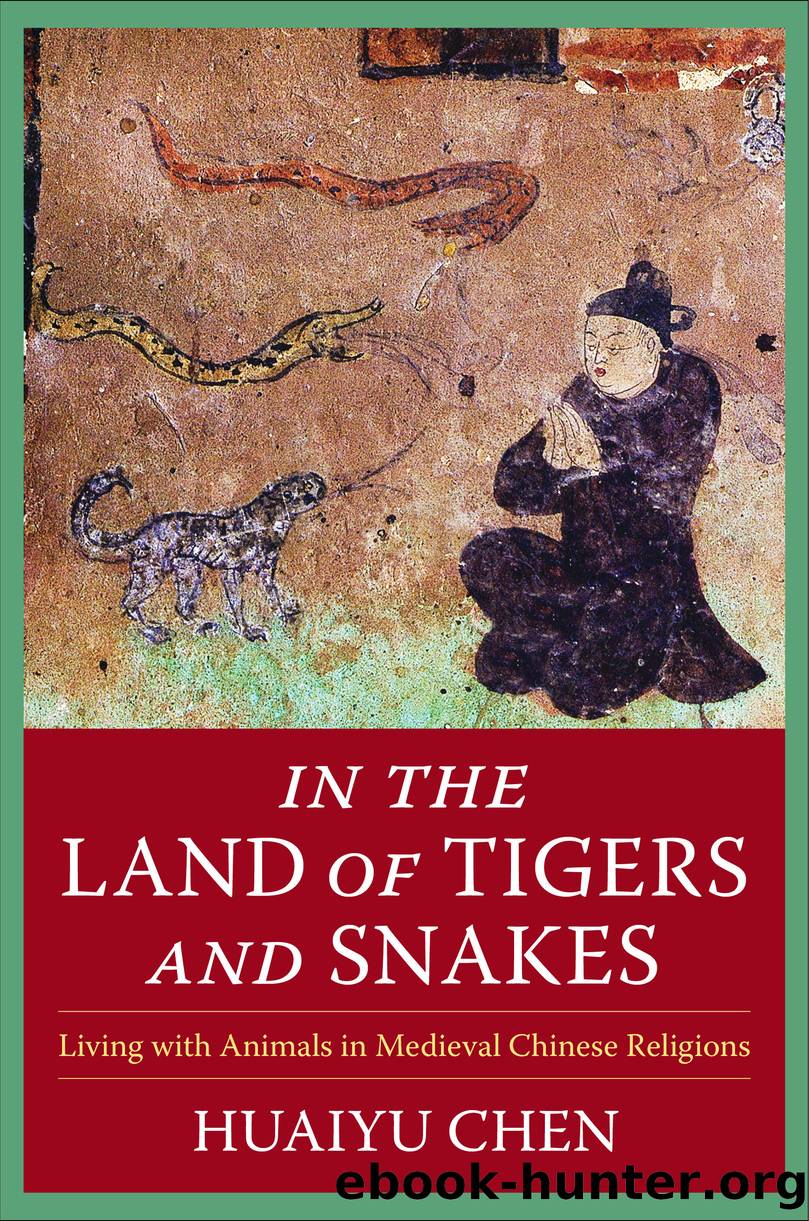

In the Land of Tigers and Snakes by Huaiyu Chen

Author:Huaiyu Chen

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Columbia University Press

CONCLUSION

In medieval Chinese Buddhism, the rules based on the traditional monastic code often could not cover all the issues monks confronted raised in daily monastic life; yet according to Daoxuan, who I discussed in chapter 1, they could be justified by doctrines. These textual rules and doctrinal principles, however, often differed from the daily experience of the monks who lived in their contemporaneous reality. In this chapter I demonstrate that dealing with snakes in early Buddhism followed the principle of nonviolence set forth in canonical texts. This legacy can also be found in medieval Chinese Buddhist texts. But medieval Chinese Buddhism faced many challenges while dealing with snakes. First, snakes and tigers posed the biggest threats toward both Buddhist and local communities. Chinese Buddhists often encountered snakes while traveling in the wilderness. Second, medieval Chinese Buddhists found that they had to engage with local communities by extending their Buddhist power to include eliminating snake disasters. Third, there was a conflict between Buddhist patriarchy and snakes in medieval China. The idea of an association between feminized snakes and women was manifested in many Chinese Buddhist narratives, especially those about miserable women whose greedy, jealous, and evil acts resulted in the karmic retribution of being reborn as snakes who would be tortured in the realm of animals. In offering confession rituals, medieval Chinese Buddhism attempted to save both women and snakes victimized by Chinese misogyny and Buddhist ophidiophobia. Fourth, medieval Chinese Buddhism faced competition from Daoism and local cultic practice.

One of the most distinctive new developments regarding the handling of snakes in medieval Chinese Buddhism was the killing of snakes to protect monks and monastic property. Although early Buddhism did not support the killing of any animal, including snakes, medieval Chinese Buddhist monks adapted the strategy of killing snakes to aid local communities, to heal illnesses in local villagers, and to compete with Daoist priests for religious power. In ancient times, Daoist priests had developed techniques and rituals for killing snakesâseen both as dangerous animals and as demonsâby mobilizing spirits and deities. Meanwhile, in medieval China, Daoist priests transformed snakes from demons into protectors of monastic properties. Snakes in medieval Daoist narratives became weapons that were used against both political power and religious adversaries.

The killing of snakes in medieval Chinese Buddhism was a new development shaped by a number of factors. First, it seems that the evolving MahÄyÄna teachings offered a doctrinal foundation for auspicious killing, with new traditions that authorized radical responses by a bodhisattva for the sake of sentient beings. Auspicious violence, such as self-immolation and killing evil sentient beings, became widely acceptable for medieval Chinese Buddhists, and sometimes even served as supportive evidence for the eminence of monastic members. Second, social and historical demands to kill snakes to benefit local communities and save local villagers drew the attention of, and a response from, Buddhist monks. Third, there were exchanges of ideas and practices between Buddhism and Daoism about how to handle venomous snakes. Buddhist monks developed techniques and rituals, and especially esoteric methods, for killing snakes to compete with Daoism.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen(4384)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(4203)

World without end by Ken Follett(3474)

Ants Among Elephants by Sujatha Gidla(3460)

Blood and Sand by Alex Von Tunzelmann(3195)

Japanese Design by Patricia J. Graham(3165)

The Queen of Nothing by Holly Black(2586)

City of Djinns: a year in Delhi by William Dalrymple(2548)

Foreign Devils on the Silk Road: The Search for the Lost Treasures of Central Asia by Peter Hopkirk(2455)

India's Ancient Past by R.S. Sharma(2450)

Inglorious Empire by Shashi Tharoor(2437)

Tokyo by Rob Goss(2427)

In Order to Live: A North Korean Girl's Journey to Freedom by Yeonmi Park(2378)

Tokyo Geek's Guide: Manga, Anime, Gaming, Cosplay, Toys, Idols & More - The Ultimate Guide to Japan's Otaku Culture by Simone Gianni(2360)

India's biggest cover-up by Dhar Anuj(2350)

The Great Game: On Secret Service in High Asia by Peter Hopkirk(2332)

Goodbye Madame Butterfly(2250)

Batik by Rudolf Smend(2179)

Living Silence in Burma by Christina Fink(2066)