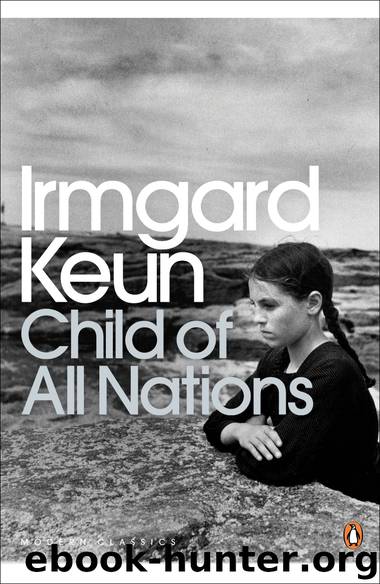

Child of All Nations by Michael Hofmann

Author:Michael Hofmann [Hofmann, Michael]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9780141908823

Publisher: Penguin Books Ltd

Published: 2008-07-15T04:00:00+00:00

Afterword

I first came to Irmgard Keun by way of the Austrian-Jewish writer Joseph Roth – for all the Roth reasons, if you like. She lived and travelled with him from June 1936 to January 1938, in the middle of her life and at the dog-end of his. (He died in May 1939.) In Joseph Roth biographies, I’d read her very striking and persuasive account of him during those terrible years of exile:

When I first met Roth in Ostende, I felt here was someone who was simply about to die of sadness. His round blue eyes were almost blind with despair, and his voice sounded as though buried under tons of grief. Later on, that impression blurred a little, because at that time Roth wasn’t just sad, he was also the greatest and most impassioned of haters…

Though always denied by Keun (admittedly, like Roth himself, she was an inveterate liar), the persistent on dit is that, at least in part – the generosity, the scrounging, the panache, the drinking, the odd mixture of unreliability and dependability – the character, or perhaps the circumstantial character, of Kully’s father, Peter, in Child of All Nations is supposed to be based on Roth’s. It didn’t matter; I ended up so charmed by Keun that I translated the whole book. On the way, I read – much of it aloud – everything else of hers I could find. I suppose it’s a little like enjoying your round, and buying the golf course.

Irmgard Keun was born in Berlin in 1905; later, she always claimed it was in 1910, the year her brother Gerd was born. The lie served two purposes: it made her appear younger, and it squashed an upstart rival. (The trauma of the arrival of a younger sibling is introduced, then gently shelved, in Child of All Nations.) She grew up in Cologne – where her father worked in the fledgling German petrol industry – and after school took to the stage. For a couple of years she played small parts in provincial rep companies, gaining, it seems, little favourable notice. She was averagely pretty, shy, willing, and not very good. Defeated as an actress, she began to write in 1929, and here she was immediately successful. She was published right away – in her own hyperbolic account, she was offered a contract within twenty-four hours – and her books sold in the tens of thousands at home, and were translated abroad. She was published by Gallimard in France, and prominently reviewed in the New York Times and The Times Literary Supplement.

In a sense, impersonation – mimicry – remained the name of the game. In her early novels, Gilgi, eine von uns (‘Gilgi, one of us’, 1931) and Das kunstseidene Mädchen (‘The artificial silk girl’, 1932), both in the first-person narrative form that remained most congenial to her, Keun gave voice to the Young Modern Woman – now newly and trickily positioned at the crux of work, love and family – much more effectively than she had been able to do as an actress in parts written by others.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Red by Erica Spindler(12578)

Crooked Kingdom: Book 2 (Six of Crows) by Bardugo Leigh(12322)

Twisted Palace by Erin Watt(11157)

Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit by John E. Douglas & Mark Olshaker(9346)

Fangirl by Rainbow Rowell(9260)

Never let me go by Kazuo Ishiguro(8904)

All the Light We Cannot See: A Novel by Anthony Doerr(8499)

A Man Called Ove: A Novel by Fredrik Backman(8442)

The Lover by Duras Marguerite(7906)

Confessions of an Ugly Stepsister by Gregory Maguire(7891)

Little Fires Everywhere by Celeste Ng(7202)

The Vegetarian by Han Kang(6303)

To All the Boys I've Loved Before by Jenny Han(5855)

The Shadow Of The Wind by Carlos Ruiz Zafón(5695)

On the Yard (New York Review Books Classics) by Braly Malcolm(5525)

Keepsake: True North #2 by Sarina Bowen(5416)

Dancing After Hours by Andre Dubus(5281)

Ken Follett - World without end by Ken Follett(4738)

The Perks of Being a Wallflower by Stephen Chbosky(4651)