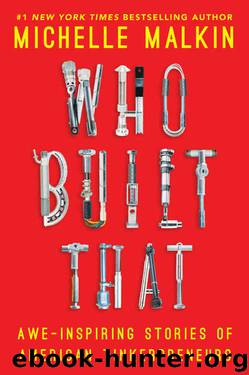

Who Built That: Awe-Inspiring Stories of American Tinkerpreneurs by Michelle Malkin

Author:Michelle Malkin [Malkin, Michelle]

Language: eng

Format: epub, mobi

Publisher: Mercury Ink

Published: 2015-05-18T22:00:00+00:00

Back to the Future: The Resurrection of Vitrum Flexile

Remember the legend of the hapless inventor who lost his head when he brought a sample of unbreakable glass to the ungrateful and insane emperor Tiberius? His workshop and recipes may have been destroyed, but his daring, inventive spirit infused the next two millennia of glass history. In 1922, another bold inventor held a demonstration of durable glass. It was Mike Owens. He held up a strip of one-foot-wide, three-feet-long glass for a reporter. “That is one of the most interesting developments in modern glass-making,” he asserted. Explaining how a Pennsylvania chemist pioneered the process of laminated glass, Owens marveled: “The extraordinary thing about it is that it does not break and fly to pieces like ordinary glass. Let me show you.”

Owens picked up a heavy paper cutter and slammed it into the glass a half-dozen times. Though some fine cracks appeared, the strip remained intact and nothing broke off. The implications for automotive safety were obvious.

The problem was that the lamination process, which involved inserting a celluloid layer between two panes of glass, required a radical new manufacturing method for flat glass. For two thousand years, artisans made windows by blowing cylinders of glass. “One side of the cylinder was then cut,” Owens explained, then reheated and flattened, “and the glass rolled flat.” Except it wasn’t completely flat. The ancient, time-consuming, and unreliable techniques for producing window glass retained a problematic curve. It had to be eliminated. But could it be done?

The man who pioneered and patented true flat-glass production and automation was engineer and inventor Irving Colburn. His Eureka! moment for manufacturing glass in a continuous, single sheet came from . . . breakfast:

Colburn’s inspiration came to him while eating pancakes. He noticed that after cutting the pancakes, the syrup clung along the length of the knife blade as he lifted it. It occurred to him that a sheet of molten glass could be pulled up in a similar manner. In his machine, the glass was pulled from the tank by the bait (iron bars), then bent over a steel roller and propelled through the annealing lehr on rollers turned by electric motors.

Colburn faced the same kinds of financial difficulties and union obstructionism that Libbey and Owens overcame. But he didn’t have their wherewithal. He had not forged the kind of critical business alliance Libbey and Owens had created. The clique of existing flat-glass manufacturers wanted no part of Colburn’s monopoly-busting ideas. The Knights of Labor stood against him. He faced rejection from dozens of glass companies. After begging and borrowing to keep his dream alive, Colburn reached out to Owens, who eagerly embraced the revolutionary idea of this kindred glass maverick. Libbey once again defied the naysayers in his corporate empire and backed Owens and Colburn.

In 1912, they approved Owens’s proposal to buy Colburn’s machine and patents for $15,000. Owens zeroed in on key mechanical flaws in Colburn’s design and embarked on a new, never-ending quest for improvement and perfection.

Download

Who Built That: Awe-Inspiring Stories of American Tinkerpreneurs by Michelle Malkin.mobi

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| American National Standards Institute (ANSI) Publications | Architecture |

| History | Measurements |

| Patents & Inventions | Research |

Whiskies Galore by Ian Buxton(40602)

Introduction to Aircraft Design (Cambridge Aerospace Series) by John P. Fielding(32359)

Small Unmanned Fixed-wing Aircraft Design by Andrew J. Keane Andras Sobester James P. Scanlan & András Sóbester & James P. Scanlan(32154)

Craft Beer for the Homebrewer by Michael Agnew(17467)

Turbulence by E. J. Noyes(7067)

The Complete Stick Figure Physics Tutorials by Allen Sarah(6654)

Kaplan MCAT General Chemistry Review by Kaplan(6078)

The Thirst by Nesbo Jo(5809)

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou(5794)

Learning SQL by Alan Beaulieu(5440)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(5062)

Man-made Catastrophes and Risk Information Concealment by Dmitry Chernov & Didier Sornette(4763)

iGen by Jean M. Twenge(4711)

Digital Minimalism by Cal Newport;(4595)

Life 3.0: Being Human in the Age of Artificial Intelligence by Tegmark Max(4530)

Audition by Ryu Murakami(4117)

Electronic Devices & Circuits by Jacob Millman & Christos C. Halkias(4058)

1,001 ASVAB Practice Questions For Dummies by Powers Rod(4054)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(4027)