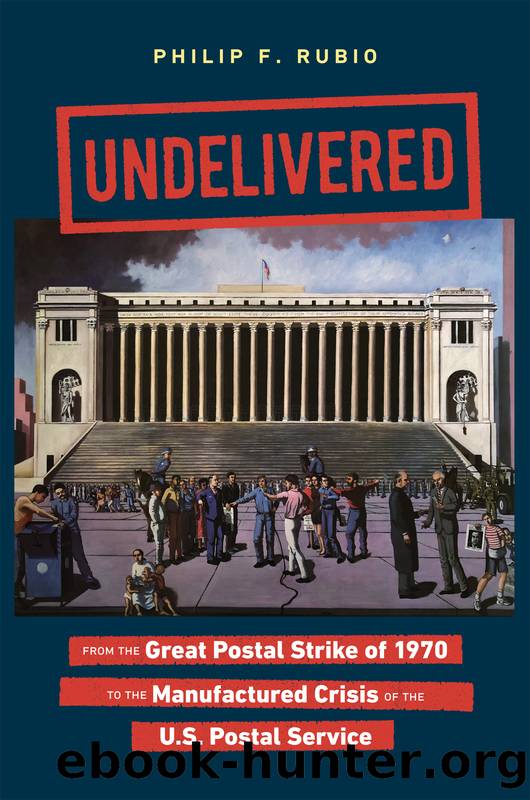

Undelivered by Philip F. Rubio

Author:Philip F. Rubio

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: The University of North Carolina Press

Published: 2020-06-15T00:00:00+00:00

The first U.S. Postal Service collective bargaining agreement was signed July 20, 1971, and included the American Postal Workers Union (APWU), National Association of Letter Carriers (NALC), National Postal Mail Handlers Union (NPMHU), and the National Rural Letter Carriers Association (NRLCA). NALC president Rademacher is seated, with (left to right) Postmaster General Winton Blount and Assistant Labor Secretary William Usery looking on. Courtesy of NALC.

Overlapping the drama of national contract negotiations was the battle between the NALC national office and Branch 36. President Rademacher began what turned into a six-month campaign to place dissident Branch 36 in trusteeship on June 25, 1971, out of fear that it was getting beyond the national control with its strike rallies and votes. “Local officers,” writes Tom Germano, “refused to surrender their positions.”19 The national office sought an injunction from a federal judge but failed. They appealed. This was the backdrop for a rally of 12,000 postal workers at the Manhattan Center on June 30, 1971.20 On December 3, 1971, a year after Vincent Sombrotto defeated Gus Johnson to become NALC Branch 36 president, national officers appeared at Branch 36 headquarters in midtown Manhattan with their attorney, police officers, and a writ to impose trusteeship. Sombrotto, along with newly elected executive vice president Tom Germano and recording secretary John Cullen, were stripped of their full-time branch positions and returned to their stations carrying mail. They were replaced by the trustees, which included Gus Johnson, NALC national officer Bernard Murphy, and NALC New York state association president Frank Merigliano. The branch did not recognize them, however, as officers.21 It was a dual-power situation. Germano argues that a major motivating factor for putting Branch 36 under trusteeship was a desire to halt the campaign by the National Rank and File Movement (NRFM)—whose stronghold was in New York—to put “one man one vote” decision-making on the ballot at the 1972 NALC convention.22 What followed was two weeks of embarrassment for Rademacher and the national office. One day during that period, over 2,000 Branch 36 members picketed their union office—then located in the Times Square Hotel at 261 West Forty-Third Street. An agreement was reached after a series of negotiations. Rademacher made and then retracted an offer. Branch 36 asked the U.S. Supreme Court to hear their appeal. Rademacher finally gave in to Branch 36’s demands and agreed to rescind the trusteeship—five minutes after Branch 36’s attorney filed an appeal.23 But the damage had been done to the burgeoning rank-and-file movement. By placing Branch 36 under trusteeship, along with merging seventy-five Long Island branches, Rademacher was able to stop the NRFM “from attaining the required number of endorsements necessary to present the question of referendum voting for national officers to the total membership prior to the national convention.”24 In 1974, the year before the NRFM’s decline, supporters of Rademacher “stole the thunder” from the NRFM by proposing resolutions that both passed, allowing voting on national officers by mail rather than being restricted to convention attendance, as well as membership voting for contract ratification.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Civilization & Culture | Expeditions & Discoveries |

| Jewish | Maritime History & Piracy |

| Religious | Slavery & Emancipation |

| Women in History |

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32561)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31958)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31944)

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(19097)

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari(14392)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13339)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12033)

Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari(5374)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(5221)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(5100)

Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow by Yuval Noah Harari(4921)

Endurance: Shackleton's Incredible Voyage by Alfred Lansing(4786)

Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl(4608)

The Silk Roads by Peter Frankopan(4537)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(4481)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(4218)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(4116)

The Motorcycle Diaries by Ernesto Che Guevara(4105)

Stalin by Stephen Kotkin(3971)