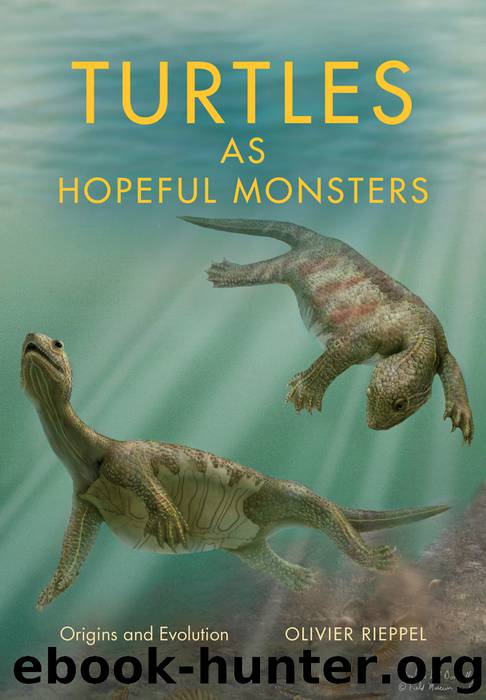

Turtles as Hopeful Monsters by Olivier Rieppel

Author:Olivier Rieppel [Rieppel, Olivier]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9780253024756

Publisher: Indiana University Press

Published: 2016-01-15T07:00:00+00:00

A German Jew in America

Richard Benedict Goldschmidt came, as he himself put it, “from an old German-Jewish family” (Stern, 1967:172; for a review of Goldschmidt’s life and work, see Dietrich, 2003). He was born in Frankfurt am Main on April 12, 1878, and died in Berkeley, California, on April 24, 1958. His parents were of high social standing, receiving “well-known scientists, bankers, and philanthropists” at their house for dinner and entertainment (Stern, 1967:141ff.). In Goldschmidt’s own words, his was “a typical German bourgeois family, comfortable but strict and even parsimonious in spite of cooks, nursemaids and French governesses” (Stern, 1967:142). Later in life, he reminisced about the antisemitic mobbing he experienced in the streets of his hometown and at school. As was typical for members of his social class in Germany, Richard enjoyed a broad, classical education in the ancient languages of Latin and Greek as well as in the humanities, arts, and sciences. “Music is still to me what religion is to the believer,” Goldschmidt once said later in his life (Stern, 1967:172). He played the violin and viola, all the while excelling in sports, and grew up to become an aficionado of Far Eastern arts. Acquaintance with the works of Goethe was de rigueur in the social circles known as the Bildungsbürgertum, as was the study of philosophical luminaries “from Spinoza to Nietzsche” (Stern, 1967:142).

At his parent’s request, he enrolled in medical school at the University of Heidelberg. What is important for a proper understanding of his later theorizing in genetics is the fact that as a medical student, Goldschmidt took classes from the most illustrious comparative anatomist of his time, Carl Gegenbaur (1826–1903), who had transferred from Jena University to Heidelberg in 1873. Gegenbaur imbued the young medical student with a deep sense of appreciation for the organization of the major body plans that mark out higher taxonomic units, such as mollusks, arthropods, and vertebrates. In the Gegenbaur school, such body plans were referred to as types of organization: turtles and birds are clearly different types of organization within vertebrates. At the outset of his academic career, while still a professor in Jena, Gegenbaur held these types as having been designed by the Creator. Gegenbaur was instrumental in bringing the young Ernst Haeckel to the University of Jena, where a deep friendship blossomed between the two men (Richards, 2008:80ff.). Ernst Haeckel immediately caught the Darwinian bug when he read the German translation of Darwin’s Origin, published by the paleontologist Heinrich Bronn (1800–1862) in 1860 (Gliboff, 2008). Soon Haeckel had managed to infect his friend Gegenbaur with that same bug. The two embarked on a joint project, which was to render comparative anatomy into what they called a true science “through its infusion with evolutionary meaning” (Nyhart, 2003:163; see also Rieppel, 2011). Whereas before comparative anatomy strove to sketch the ideal, i.e., purely conceptual, derivation of one body plan from another through a series of imagined intermediate stages, it now attempted to understand the origin and transformation of body plans in evolutionary terms.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari(13054)

The Tidewater Tales by John Barth(12030)

Do No Harm Stories of Life, Death and Brain Surgery by Henry Marsh(6337)

Mastermind: How to Think Like Sherlock Holmes by Maria Konnikova(6236)

The Thirst by Nesbo Jo(5786)

Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams by Matthew Walker(5642)

Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari(4537)

Life 3.0: Being Human in the Age of Artificial Intelligence by Tegmark Max(4509)

The Longevity Diet by Valter Longo(4445)

The Rules Do Not Apply by Ariel Levy(3906)

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot(3826)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(3802)

Why We Sleep by Matthew Walker(3773)

Animal Frequency by Melissa Alvarez(3755)

Yoga Anatomy by Kaminoff Leslie(3702)

Barron's AP Biology by Goldberg M.S. Deborah T(3632)

The Hacking of the American Mind by Robert H. Lustig(3580)

All Creatures Great and Small by James Herriot(3517)

Yoga Anatomy by Leslie Kaminoff & Amy Matthews(3396)