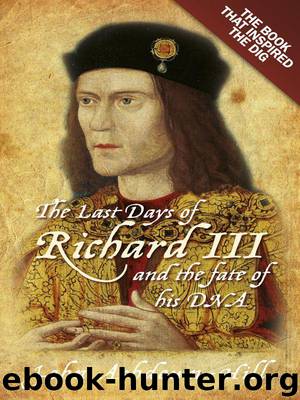

The Last Days of Richard III and the fate of his DNA: The Book that Inspired the Dig by John Ashdown-Hill

Author:John Ashdown-Hill

Language: eng

Format: mobi, epub

Publisher: The History Press

Published: 2013-01-31T00:00:00+00:00

I, here, whom the earth encloses under various coloured marble,13

Was justly called Richard the Third.14

I was Protector of my country, an uncle ruling on behalf of his nephew.

I held the British kingdoms in trust, [although] they were disunited.

Then for just15 sixty days less two,

And two summers, I held my sceptres.

Fighting bravely in war, deserted by the English,

I succumbed to you, King Henry VII.

But you yourself, piously, at your expense, thus honoured my bones

And caused a former king to be revered with the honour of a king16

When [in] twice five years less four17

Three hundred five-year periods of our salvation had passed.18

And eleven days before the Kalends of September19

I surrendered to the red rose the power it desired.20

Whoever you are, pray for my offences,

That my punishment may be lessened by your prayers.

While the manuscript texts and Sandford’s publication contain slightly different readings at some points, the major part of the text is identical in all the currently extant versions.

So was this epitaph actually inscribed on the tomb of c. 1494? This point cannot be absolutely proved either way, since there was a well-authenticated fifteenth-century tradition of epitaphs inscribed on tablets of wood, or on parchment, and hung by admirers around the tombs of the famous. It is therefore possible that Richard III’s epitaph was not directly inscribed on the tomb, but hung up nearby. Even so, the text remains interesting. It is generally favourable to Richard, and certainly not overtly hostile. It seems highly improbable that any writer of the ‘Tudor’ period would have dared to pen a valedictory text on Richard III without the authorisation of the reigning monarch. Thus we must assume that the text reflects the ‘official viewpoint’ of Henry VII’s regime on Richard III in about 1494.

If the epitaph may be regarded as an ‘official statement’ by the government of Henry VII on Richard III, it is certainly of interest. Unsurprisingly, perhaps – for this is a theme encountered in other ‘Tudor’ sources – it pays tribute to Richard’s bravery. The final couplet has sometimes been seen as implying that Richard was evil (and Buck’s verse translation, which employs the word ‘crimes’, certainly carries that flavour). In fact, however, the closing lines merely reflect the standard late medieval preoccupation with purgatory, common to all believers at the time when Richard’s tomb was erected. It was normal in tomb inscriptions to request prayers for the deceased, and the fact that this epitaph does so need not imply that Richard III was more in need of such prayers than other people.

The text of the epitaph, together with the fact that it is not overtly hostile to Richard, raises a broader question. Why did Henry VII decide, nine or ten years after Richard’s death, to create a monument for him? Had Henry simply mellowed as time passed? Did he come to feel sorry for Richard? Was it that sufficient time had elapsed for him to feel that a memorial to Richard would now be safe?

Early in 1493, having already survived an

Download

The Last Days of Richard III and the fate of his DNA: The Book that Inspired the Dig by John Ashdown-Hill.epub

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Military | Political |

| Presidents & Heads of State | Religious |

| Rich & Famous | Royalty |

| Social Activists |

Waking Up in Heaven: A True Story of Brokenness, Heaven, and Life Again by McVea Crystal & Tresniowski Alex(37794)

Empire of the Sikhs by Patwant Singh(23074)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19035)

Hans Sturm: A Soldier's Odyssey on the Eastern Front by Gordon Williamson(18579)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13319)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12018)

Tools of Titans by Timothy Ferriss(8369)

Educated by Tara Westover(8047)

How to Be a Bawse: A Guide to Conquering Life by Lilly Singh(7472)

Permanent Record by Edward Snowden(5839)

The Last Black Unicorn by Tiffany Haddish(5630)

The Rise and Fall of Senator Joe McCarthy by James Cross Giblin(5275)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(5144)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(5092)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4954)

The Crown by Robert Lacey(4807)

The Iron Duke by The Iron Duke(4350)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(4103)

Stalin by Stephen Kotkin(3958)