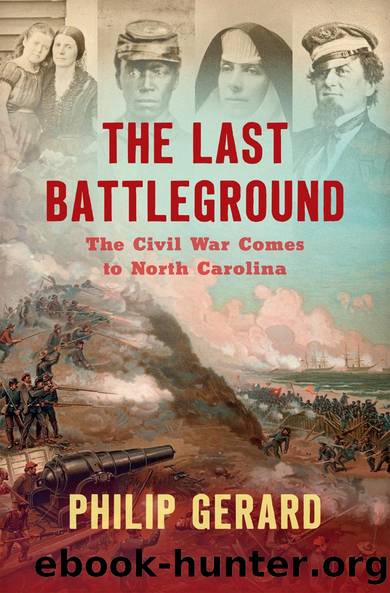

The Last Battleground by Philip Gerard

Author:Philip Gerard [Gerard, Philip]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: Biography & Autobiography, General, History, Military, United States, Civil War Period (1850-1877), State & Local, South (AL; AR; FL; GA; KY; LA; MS; NC; SC; TN; VA; WV)

ISBN: 9781469666112

Google: 3qVYzgEACAAJ

Publisher: University of North Carolina Press

Published: 2021-08-15T22:33:05+00:00

26

WRITING THE WAR

Jacob Nathaniel Raymer is a literary adventurer: a lean, handsome young man with a long, angular face, a strong nose, and intense eyes. At age twenty-one, he leaves his home in Catawba County and strikes out for the westâArkansasâhis mind set on seeing the world beyond the mountains. At Swannanoa Gap, east of Asheville, he lingers for a last look homeward, âand from that lofty pinnacle, the dividing line between home and strangers,â he writes in his diary, âI did take a long farewell.â

Well-read and already erudite, he composes a wistful poem of 201 lines, preoccupied with death and loss, that he titles, âA Last View of Home.â âKnowing that / Life at best, is uncertain as the wind,â he writes, âAnd man, with deathâs ghostly messengers / On all sides is besetâ. Nor leaves behind / A memento of his existence. ⦠Fame dies with the individual.â

His Arkansas sojourn lasts just a couple of years, and by 1860 he is back home, living with his parents and teaching at the Common Schools. On June 7, 1861, soon after North Carolina secedes from the Union, Raymer crosses the county line into Iredell to join Company C of the 4th North Carolina Infantry as a private soldier and musician. Before setting off for training at Garysburg, he visits his schoolhouse one last time. The young scholars strike up a chorus of âMount Vernon,â and Raymer joins in. âBut when we began âUnity,â my voice failedâI could not singâI felt so sad! So strange!â

His company is nicknamed the Saltillo Boys, since it includes some veterans of the Mexican War. Raymer begins a journal he will keep faithfully throughout four years of war, chronicling nearly every major battle in the east: the Peninsula Campaign, the Seven Days Battles, Sharpsburg, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg, the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Court House, the Shenandoah Valley Campaign of 1864, the siege of Petersburg, and the last stand at Appomattox.

Raymer draws from his copious, detailed notes to write letters homeânot to his parents, but to a public audience. By choice, he becomes one of the Confederacyâs corps of a hundred-odd war correspondents. Many of them, like Raymer, are soldiers who send home letters to their local newspapers as circumstances allow. In the Confederacy, a letter may take a month or more to reach its destination, and the 50,000 miles of telegraph lines in the eastern states, like most other resources, are heavily concentrated in the North.

Some paid correspondents work as part of a ragged consortium called the Press Association of the Confederate Statesâcounterpart to the newly formed Associated Press in New Yorkâbut with few of APâs resources.

The Northern newspapers, by contrast, field more than 500 paid correspondents, although they are not well paid. The New York Herald alone sends 63 correspondents into the field, and its sister papers, the Times and the Tribune, each send 20. Mostly young, untrained, and inexperienced on a battlefield, the correspondents earn only $10 to $25 per week, including expenses, which can be exorbitant in the war zone.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Afghan & Iraq Wars | American Civil War |

| American Revolution | Vietnam War |

| World War I | World War II |

Waking Up in Heaven: A True Story of Brokenness, Heaven, and Life Again by McVea Crystal & Tresniowski Alex(37775)

Empire of the Sikhs by Patwant Singh(23065)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19028)

Hans Sturm: A Soldier's Odyssey on the Eastern Front by Gordon Williamson(18561)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13300)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12009)

Tools of Titans by Timothy Ferriss(8357)

Educated by Tara Westover(8040)

How to Be a Bawse: A Guide to Conquering Life by Lilly Singh(7464)

Permanent Record by Edward Snowden(5822)

The Last Black Unicorn by Tiffany Haddish(5621)

The Rise and Fall of Senator Joe McCarthy by James Cross Giblin(5264)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(5137)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(5084)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4942)

The Crown by Robert Lacey(4795)

The Iron Duke by The Iron Duke(4341)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(4088)

Stalin by Stephen Kotkin(3949)