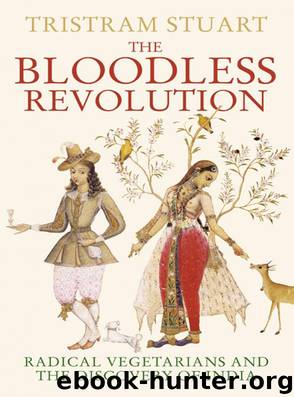

The Bloodless Revolution by Tristram Stuart

Author:Tristram Stuart [Tristram Stuart]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9780007404926

Publisher: HarperCollins Publishers

* * *

*See chapter 15.

*Oswald was, of course, Scottish.

*Duc D’Orléans, nicknamed ‘Philippe Egalite’ for his leading role in the Revolution.

TWENTY-THREE

Bloodless Brothers

In France the vegetarian radicals came close to the centre ground of revolutionary politics. In Britain the authorities – horrified by the scenes of decapitation and civil war over the Channel – were determined to stamp out the rebels before it was too late. Many radicals were fomenting revolution in Britain, the monarchy of George III was in almost perpetual crisis, and by the time of Valady’s execution the thought police were poised for a vigorous crackdown. The British revolutionaries – with a thriving network of vegetarians among them – had become a force to be reckoned with.

Jacques-Pierre Brissot, the French revolutionary leader who patronised Oswald and Valady, regularly visited London to cultivate political alliances. As a frequent guest at the London household of ‘the Pythagorean Pigott’, Brissot became friends with several others who extended their ‘fraternity’ to animals, and he made detailed comments about them in his Mémoires. Prominent among these was the Welsh druid-priest David Williams, notorious for disseminating his pagan-influenced pantheism from the Temple of Nature in Cavendish Square. Influential in Bonneville and Oswald’s Masonic Social Circle, Williams agitated in France and England and he set up a Literary Fund which subsidised Oswald’s activities.1 His Lectures on Education revived the principles of Rousseau’s Émile, including the Pythagorean attention to dietary temperance, and Brissot referred to Williams cordially as an ‘apostle’ of vegetarianism.2

Williams in fact ended up turning against vegetarianism, but his Utilitarian argument proving ‘the false humanity of the Pythagorean system’ was nevertheless emphatically animal-friendly – like the arguments of Francis Hutcheson and William King on which it was based.3 If farm animals were made happy through careful husbandry, he explained in his Lectures on the Universal Principles and Duties of Religion and Morality (1789), then cultivating as many animals as possible for human consumption would create more happy creatures than if we all just ate vegetables. Thus, he concluded, ‘humanity pleads in conjunction with reason; and thereby encreasing the general sum of happiness in the world, it is reconciled to what at first appears inhuman, submitting the life of one animal to another.’ Vegetarianism, he explained, was one of those ‘excesses of tender passions, [which] delight and fascinate, while they mislead and injure us’. Without these reasons, he insisted, ‘I should certainly have continued, what I once was, a thorough Pythagorean.’ Despite his apostasy from vegetarianism, however, Williams held on to his conviction that evil could be eradicated on earth if everyone emulated the Hindus in exercising compassion to ‘all living creatures’, and this helped many radicals to see why the ‘social circle’ should be widened beyond the confines of the human race.4

At Pigott’s London house, Brissot also became closely acquainted with the arch-quack James Graham (1745–94), ‘so famous for his electric bed, his earth baths, his Pythagoreanism,’ commented Brissot, ‘and by twenty other systems not less bizarre that he had preached in the American continent’.5

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Culinary Biographies | Essays |

| Food Industry | History |

| Reference |

For the Love of Europe by Rick Steves(4784)

The Sprouting Book by Ann Wigmore(3143)

Better Homes and Gardens New Cookbook by Better Homes & Gardens(3062)

BraveTart by Stella Parks(3050)

The Death of the Heart by Elizabeth Bowen(3008)

Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat: Mastering the Elements of Good Cooking by Nosrat Samin(2747)

Sauces by James Peterson(2669)

Classic by Mary Berry(2586)

Solo Food by Janneke Vreugdenhil(2569)

The Bread Bible by Rose Levy Beranbaum(2562)

Ottolenghi - The Cookbook by Yotam Ottolenghi(2443)

Kitchen confidential by Anthony Bourdain(2440)

Martha Stewart's Baking Handbook by Martha Stewart(2408)

Betty Crocker's Good and Easy Cook Book by Betty Crocker(2356)

Day by Elie Wiesel(2331)

Hot Sauce Nation by Denver Nicks(2170)

The Plant Paradox by Dr. Steven R. Gundry M.D(2135)

My Pantry by Alice Waters(2124)

The Kitchen Counter Cooking School by Kathleen Flinn(2086)