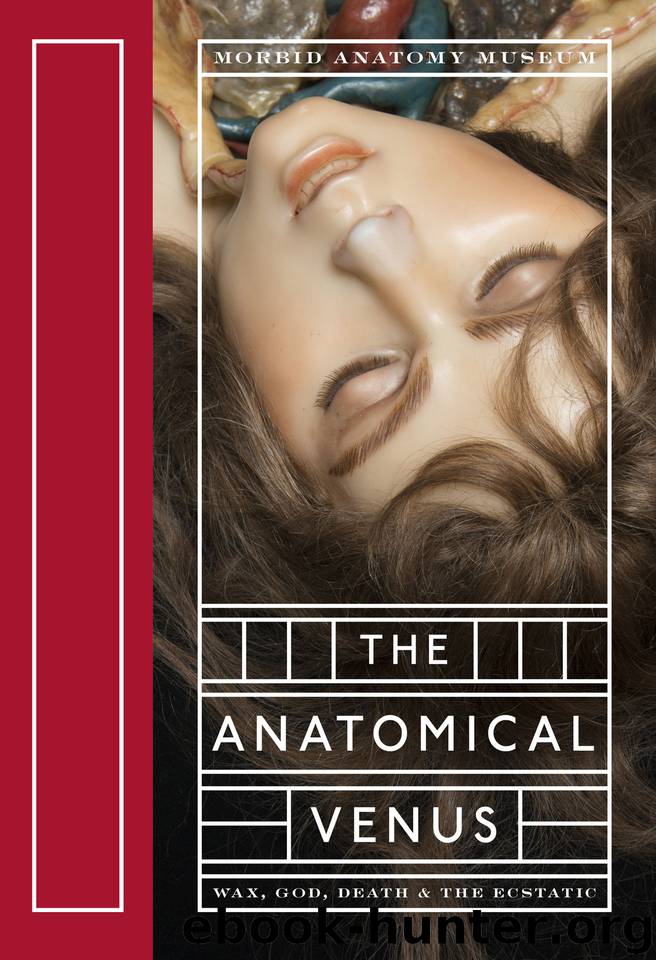

The Anatomical Venus by Joanna Ebenstein

Author:Joanna Ebenstein [Ebenstein, Joanna]

Language: eng

Format: azw3

Publisher: Distributed Art Publishers

Published: 2017-01-02T16:00:00+00:00

flAV_00966_pre-pdf layout_001_215.indd 142 12/01/2016 12:14 [3]

AV_00966_pre-pdf layout_001_215.indd 143 13/01/2016 12:38 [3]

fiAV_00966_pre-pdf layout_001_215.indd 144 12/01/2016 12:14 [3]

AV_00966_pre-pdf layout_001_215.indd 145 12/01/2016 12:1

AV_00966_pre-pdf layout_001_215.indd 146 12/01/2016 12:14 [3]

AV_00966_pre-pdf layout_001_215.indd 147 12/01/2016 12:14 [3]

(148) Although these displays can easily be dismissed or demonized as pure voyeurism, they were instructive as well as sensational and titillating. As Maritha Rene Burmeister points out, popular medical museums enjoyed a good reputa tion for many years, even being recommended in reviews by respected medical journals such as the Lancet and the Medical Times and Gazette. When Signor Sarti’s exhibition—a collection of anatomical waxworks featuring an Anatomical Venus and an Anatomical Adonis—opened in London in 1839, the distinguished literary magazine Athenaeum recommended it to ‘younger male readers’ who wanted to obtain ‘a few general ideas on the subject of anatomy, which they may do without labour or disgust’. The study of his models, claimed Sarti, would give the visitor ‘the power to communicate intelligibly with his medical advisor’ and ‘teach him the absolute necessity of putting implicit faith in those men who have made Anatomy and Physiology the study of their lives’. The English surgeon Sir Erasmus Wilson (1809–84) even wrote in 1847 that the exhibition offered ‘an unanswerable argument against Atheism’. fig. 69 fig. 69 A crowd gathers in the Kopstadtplatz, Essen, Germany, in 1889, to see Theatre Rob Melich, a travelling show that presented open-air expositions and a variety of theatrical performances at public fairgrounds. Melich eventually turned his establishment into a cinema. Such museums became increasingly associated with quack medics, who would sometimes use the horrifying effects of their exhibits as bait for busi ness, and consequently developed a bad reputation. Popular medical museums would often house the more graphic displays in a separate room for men only. A ‘doctor’ would be available on the premises (for an additional fee, of course) to provide counsel and prescribe patent medications, usually with a mercury base, to gentlemen worried that their own ‘night with Venus’ might, as the popular maxim warned, have led to ‘a lifetime with Mercury’. By 1857, the Lancet, who had once lauded such displays, now described Kahn’s Anatomical Museum—one of the largest and longest-running in London—as a place seeking to ‘excite the prurient imagination of the young by a stealthy exhibition of obscene prints, figures and books’. Here, ‘the ingenious youth, the desponding hypochondriac, or the exhausted roué…his mind duly excited by gazing upon the waxy charms of a “magnificent full-length model of AV_00966_pre-pdf layout_001_215.indd 148 12/01/2016 12:14 chapter three[3]

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Erotica | Human Figure |

| Landscapes & Seascapes | Plants & Animals |

| Portraits | Religious |

| Science Fiction & Fantasy | Women in Art |

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(16606)

Red Sparrow by Jason Matthews(4654)

Harry Potter 02 & The Chamber Of Secrets (Illustrated) by J.K. Rowling(3289)

In a Sunburned Country by Bill Bryson(2941)

Figure Drawing for Artists by Steve Huston(2791)

The Daily Stoic by Holiday Ryan & Hanselman Stephen(2703)

Drawing Cutting Edge Anatomy by Christopher Hart(2670)

The Roots of Romanticism (Second Edition) by Berlin Isaiah Hardy Henry Gray John(2564)

Japanese Design by Patricia J. Graham(2552)

Make Comics Like the Pros by Greg Pak(2420)

Stacked Decks by The Rotenberg Collection(2266)

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows (7) by J.K. Rowling(2212)

On Photography by Susan Sontag(2126)

Draw-A-Saurus by James Silvani(2102)

Tattoo Art by Doralba Picerno(2079)

Foreign Devils on the Silk Road: The Search for the Lost Treasures of Central Asia by Peter Hopkirk(2052)

The Traveler's Gift by Andy Andrews(2007)

Churchill by Paul Johnson(2006)

Drawing and Painting Birds by Tim Wootton(1997)