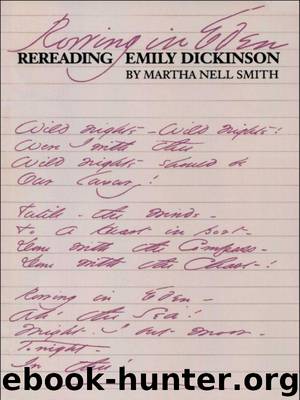

Rowing in Eden: Rereading Emily Dickinson by Smith Martha Nell

Author:Smith, Martha Nell [Smith, Martha Nell]

Language: eng

Format: azw3

Tags: -

Publisher: University of Texas Press

Published: 2010-07-04T16:00:00+00:00

Superficially, this appears sadomasochistic, but Dickinson quickly overturns the obvious. Fusing images of giddy, presumably literary (signified by the quotation marks) nature and celebration, then oxymoronically presenting a usually destructive and separative act—cutting—as one of consummate union, Dickinson, on the creative field in her Eden of experience, appropriates the site of crucifying wounds to rewrite the biblical myth of human creation and tell a story about relations between two women who, like Adam and Eve, are flesh of one another’s flesh, limbs of one another’s limbs. In contrast to the perpetual reinscription of the myth evident in the patriarchal system of naming, Dickinson’s letter-poem revises the story and its characters.28 Though she penned fantastically erotic letters to Kate Anthon, marvelously comic and loving ones to the Nor-crosses and Elizabeth Holland, and friendly enough letters to Hunt Jackson, Dickinson did not write any other woman in quite this way, describing an emotional and intellectual engrossment in terms that transform what promises to be a gory scene of bloodletting into that of female figures who cannot be crucified.29 In fact, when Dickinson writes the Nor-crosses—“I know I love my friends—I feel it far in here where neither blue nor black eye goes, and fingers cannot reach” (L 382, winter 1877)—she underscores just how monumental is the orgasmic suffusion of selves described in her letter to Sue. Thus her own writing in the “book” to Sue contextualizes “I could not drink / it Sue” to encourage interpreting it without diminishing irony.

The tone ascribed to any expression predicates interpretation, and Dickinson’s many remarks about voices and inflections indicate her sensitivities to modulation’s power over meaning and are useful to keep in mind as we formulate interpretation of her declarations to Sue. Though some maintain that Dickinson produced her poetry only for writing and never for speech, especially in the context of her statements like “The Ear is the last Face. We hear after we see” (L 405, January 1874; LF 1 – 7), accounts of those closest to her suggest that she may have tried out various tones of her written expressions by reading aloud to a trusted audience. In a March 26, 1904, letter to the editors of the Boston Woman’s Journal, Dickinson’s beloved Louise Norcross makes it plain that she knew about her cousin’s literary work and provides a rare portrait of the woman poet at work, writing and reading aloud amid the duties of housekeeping: “Mrs. Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote her most wonderful sentences on slips of paper held against the kitchen wall while she was hovering over culinary formations. And I know that Emily Dickinson wrote most emphatic things in the pantry, so cool and quiet, while she skimmed the milk; because I sat on the footstool behind the door, in delight, as she read them to me. The blinds were closed, but through the green slats she saw all those fascinating ups and downs going on outside that she wrote about.” Here “Loo” promotes her cousin by placing her in the company of the nineteenth century’s most widely read American author.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anthropology | Archaeology |

| Philosophy | Politics & Government |

| Social Sciences | Sociology |

| Women's Studies |

The Rules Do Not Apply by Ariel Levy(4953)

On the Front Line with the Women Who Fight Back by Stacey Dooley(4856)

The Lonely City by Olivia Laing(4796)

Bluets by Maggie Nelson(4542)

The Confidence Code by Katty Kay(4247)

Three Women by Lisa Taddeo(3419)

Not a Diet Book by James Smith(3409)

Inferior by Angela Saini(3310)

Confessions of a Video Vixen by Karrine Steffans(3295)

A Woman Makes a Plan by Maye Musk(3244)

Pledged by Alexandra Robbins(3169)

Wild Words from Wild Women by Stephens Autumn(3137)

Nice Girls Don't Get the Corner Office by Lois P. Frankel(3034)

Brave by Rose McGowan(2817)

Women & Power by Mary Beard(2763)

Why I Am Not a Feminist by Jessa Crispin(2738)

The Clitoral Truth: The Secret World at Your Fingertips by Rebecca Chalker(2708)

The Girl in the Spider's Web: A Lisbeth Salander novel, continuing Stieg Larsson's Millennium Series by Lagercrantz David(2706)

I Who Have Never Known Men by Jacqueline Harpman(2606)